Background

Scarlet fever is an illness caused by infection with Streptococcus pyogenes that most commonly occurs in childhood (peak age = 7–8 years old). It is characterized by an erythematous, sandpaper-like rash due to one of several erythrogenic exotoxins produced by group A streptococci. Scarlet fever typically occurs with streptococcal pharyngitis but may rarely develop with skin or wound infections. Aside from the widespread rash, scarlet fever has the same sequelae and treatment as streptococcal pharyngitis without a rash. Cases typically follow a seasonal pattern, more commonly arising in late fall, winter, and spring. S. pyogenes has over 240 distinct serotypes based on M-protein serotype and the more discriminating M-protein gene sequencing (known as emm types).1

Because scarlet fever is a reportable disease in England, a large increase in incident cases was identified in 2014. This increase has continued to persist throughout the country. Public health surveillance identified a 3- to 4-fold increase in incidence of scarlet fever, which has significantly impacted schools and nurseries in the country.2 Strains of S. pyogenes that were emm typed during this time period demonstrated a wide variety of M-protein gene sequences, but a new emm1 strain (M1UK) that is genotypically distinct from other pandemic emm1 isolates has increased in prevalence in England as invasive streptococcal disease has also risen.3,4 Although increased incidence of scarlet fever had been described in parts of Asia since 2008, England was the first European country to detect a sudden large-scale increase in cases, and this discovery has led to concern about similar widespread outbreaks occurring in other areas of the world.2

Scarlet fever is not a reportable disease in the U.S.,5 and military surveillance currently does not routinely perform M-protein gene sequencing on group A streptococcus isolates. However, diagnoses of scarlet fever can be identified throughout the Military Health System (MHS) using International Classification of Diseases, 9th and 10th Revision (ICD-9 and ICD-10, respectively) codes. The objectives of this brief report were to review scarlet fever incidence in the MHS among patients under 17 years of age and to identify any large spikes in annual cases at military treatment facilities, particularly at the bases located in England.

Methods

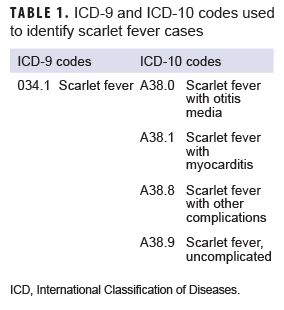

The surveillance period was 1 Jan. 2013 through 31 Dec. 2018. The surveillance population consisted of beneficiaries of the MHS who were under 17 years of age at the time of the incident diagnosis. Diagnoses of scarlet fever were ascertained from the Defense Medical Surveillance System, which includes administrative records of all medical encounters of individuals who received care in fixed (i.e., not deployed or at sea) medical facilities in the MHS or in civilian facilities when care was reimbursed by the MHS (i.e., Click to closePurchased CareThe TRICARE Health Program is often referred to as purchased care. It is the services we “purchase” through the managed care support contracts.purchased care). For surveillance purposes, an incident case of scarlet fever was defined by a qualifying ICD-9 or ICD-10 diagnosis code (Table 1) in any diagnostic position of a record of a hospitalization or an outpatient medical encounter. The incidence date was considered the date of the first hospitalization or outpatient medical encounter that included a case-defining diagnosis. An individual could be counted as an incident case of scarlet fever only once during the surveillance period; any beneficiary with a diagnosis of scarlet fever before the surveillance period was excluded from the analysis. Counts of scarlet fever diagnoses and incidence rates were calculated for each year of the surveillance period. Incidence rates were calculated as incident scarlet fever diagnoses per 10,000 person-years (p-yrs) and were stratified by selected demographic characteristics. Denominators for incidence rate calculations were calculated by identifying the number of beneficiaries who had at least 1 medical encounter during each year of the surveillance period. Diagnoses and incidence rates were calculated for the entire MHS in the primary analysis.

A secondary analysis was designed to identify a possible increasing trend in scarlet fever diagnoses in MHS beneficiaries receiving care in England during the surveillance period. For this analysis, cases were restricted to those who received a scarlet fever diagnosis at a facility located in England as identified through the Defense Medical Information System Identifier.

Results

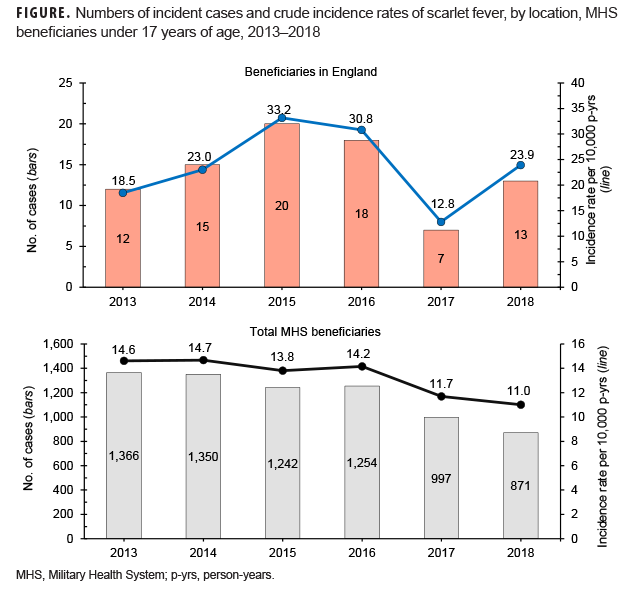

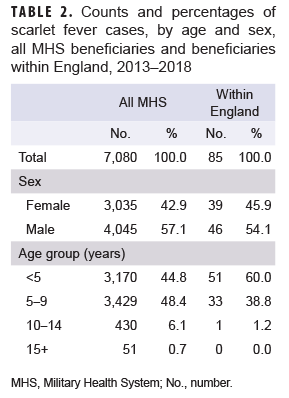

During the 6-year surveillance period, a total of 7,080 MHS beneficiaries under age 17 received an incident diagnosis of scarlet fever; 85 incident cases of scarlet fever were identified in MHS beneficiaries receiving care in England. A slightly greater proportion of cases was diagnosed among male beneficiaries, while the vast majority of cases occurred in beneficiaries under age 10 (Table 2). Across all MHS beneficiaries, the greatest number of scarlet fever cases occurred in 2013 (n=1,366) and the lowest number of cases occurred in 2018 (n=871). In contrast, in MHS beneficiaries receiving care in England, the greatest number of scarlet fever cases occurred in 2015 (n=20) and the lowest number of cases in 2017 (n=7) (Figure).

Across the MHS as a whole, crude annual incidence rates of scarlet fever diagnoses were relatively stable from 2013 through 2016 and then declined throughout the remainder of the surveillance period. In contrast, crude annual incidence rates among MHS beneficiaries in England increased almost 80% from 2013 through 2015. Subsequently, crude incidence rates declined slightly in 2016 to 30.8 cases per 10,000 p-yrs before declining to their lowest rates during the period in 2017. Rates increased again in 2018 to 23.9 cases per 10,000 p-yrs (Figure).

Editorial Comment

In 2014, England experienced a large and unexpected increase in cases of scarlet fever over the previous year, and the increase in cases continued unabated through 2018. Results of the current analysis suggest that a similar increase in cases was seen in MHS beneficiaries in England between 2013 and 2015 and again in 2018, although scarlet fever incidence rates across the entire MHS were relatively stable during the same period.

While this brief report demonstrates that MHS beneficiaries in England did have increased incidence of scarlet fever during a period while England was experiencing an outbreak, it is more difficult to interpret scarlet fever rates across the MHS. A comparison between rates in the entire MHS cohort and the MHS England cohort could be impacted by differential coding practices in England versus other locations in the MHS. Because scarlet fever is not a reportable illness in the U.S., physicians may be more likely to code a streptococcal illness (e.g., strep pharyngitis) and rash separately, rather than using a specific scarlet fever code. Future analyses of all streptococcal infection diagnoses could provide some clarification of this issue. In addition, it is likely that medical providers in England were aware of the ongoing outbreak there and thus more likely to detect and diagnose scarlet fever cases when they presented in American beneficiaries (i.e., detection bias).

Although the increase in incidence rates of scarlet fever in England is striking, it is important to recognize that the increase in the number of cases from year to year was relatively small. Only 85 cases were ascertained over 6 years among MHS beneficiaries in England, and the largest increase in the absolute number of cases was 6 cases from 2017–2018. When the numbers of cases used to compute rates are small, those rates can have poor reliability. This significant limitation should be considered when interpreting these data. Another limitation is that denominators used in the calculation of incidence rates were based on the number of beneficiaries who sought care at least once during the year rather than the number of beneficiaries eligible for care. Therefore, the denominator used for these calculations is likely an underestimate of the true denominator.

Fluctuations in crude annual rates of scarlet fever are likely due to a number of factors that include the number and emergence of new strep A strains, how widely those strains may be circulating, and the degree of immunity to those strains in a susceptible population. One possible reason for the increase in England has been attributed to a new emm1 strain of S. pyogenes,3 but it is unclear whether, and to what extent, this may have impacted rates of scarlet fever in MHS beneficiaries. Laboratory surveillance of this and other emerging strains in military populations may be warranted.

Wherever DOD personnel and their families are stationed, they are at risk from infectious outbreaks in the local community and/or country. This brief report provides an example of the importance of monitoring local public health reports to provide optimal medical care to active duty members and MHS beneficiaries.

Author affiliations: Department of Preventive Medicine and Biostatistics, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, MD (Maj Sayers); Defense Health Agency, Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch (Mr. Bova, Dr. Clark).

References

- Committee on Infectious Diseases, American Academy of Pediatrics. Red Book: 2018–2021 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 31st ed. Itasca, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2018.

- Lamagni T, Guy R, Chand M, et al. Resurgence of scarlet fever in England, 2014–16: a population-based surveillance study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18(2):180–187.

- Lynskey NN, Jauneikaite E, Li HK, et al. Emergence of dominant toxigenic M1T1 Streptococcus pyogenes clone during increased scarlet fever activity in England: a population-based molecular epidemiological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19(11):1209–1218.

- Brouwer S, Lacey JA, You Y, Davies MR, Walker MJ. Scarlet fever changes its spots. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19(11):1154–1155.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Group A streptococcal (GAS) disease. https://www.cdc.gov/groupastrep/surveillance.html. Accessed 24 Sept. 2019.