Norovirus (NoV) infections are a leading cause of acute gastroenteritis outbreaks in both the U.S. and worldwide.1 Although most cases of NoV illness are mild and self-resolving, NoV outbreaks can cause significant morbidity in military personnel and have a significant operational impact on affected units.2,3

NoV outbreaks are difficult to prevent because of several characteristics. NoVs are highly contagious and transmitted through multiple routes, including person-to-person direct contact and exposure to contaminated food, water, aerosols, and fomites. NoVs have demonstrated long-term stability in the environment and resistance to temperature extremes and standard disinfection methods. Human infections with NoV are associated with a prolonged shedding period that promotes secondary transmission. Finally, previous NoV infection often does not confer lasting immunity to reinfection with the same NoV strain or to different strains.4

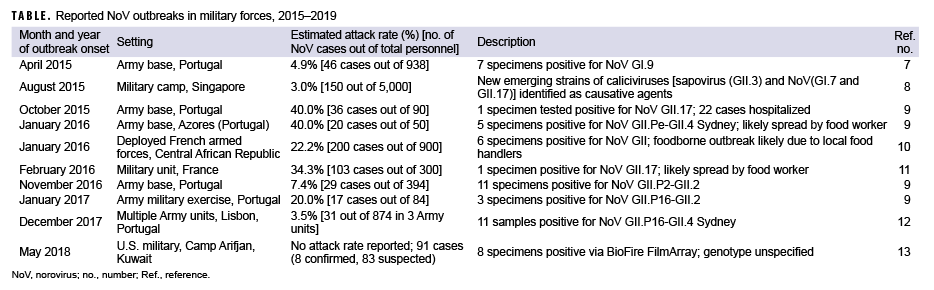

Previously, the MSMR has summarized published reports of NoV outbreaks in military forces.5,6 This update captures NoV outbreak reports in military forces published in the 5-year period between 2015 and 2019 (Table).7–13 The surveillance period included the years 2015 and 2016 (covered in a previous report) in order to identify NoV outbreak reports published since the last MSMR summary. Attack rates are provided when explicitly stated or when they could be derived from the data provided in published reports. This summary includes only outbreaks in military settings where the authors explicitly reported NoVs as a primary cause of the outbreak.

Several of the published reports documented significant operational impacts due to the NoV outbreak. Notably, the Camp Arifjan outbreak (and the public health response to contain it) resulted in the shutdown of a key personnel transit station in the U.S. Central Command for approximately 10 days,13 while the 2016 outbreak among French military personnel resulted in the cancellation of a field exercise because of a lack of personnel able to participate.11

The number of military-associated NoV outbreaks reported in peer-reviewed literature likely represents only a small fraction of all NoV outbreaks in military populations. During the surveillance period in this update, several large, military-associated NoV outbreaks were also reported in the press. Notable examples include a 2017 NoV outbreak originating in base child care centers at Hurlburt Field (the headquarters of the Air Force's 1st Special Operation Wing) that resulted in more than 100 cases14 and a 2019 outbreak at the U.S. Air Force Academy that affected about 400 cadets.15 Military enteric disease surveillance programs also routinely identify NoV outbreaks that are not published in the peer-reviewed literature. For example, between 2011 and 2016, the Naval Health Research Center's Operational Infectious Disease Directorate identified 18 NoV GI- and 26 NoV GII-associated outbreaks in U.S. military recruits.16 This finding highlights the importance of enteric disease surveillance programs in accurately quantifying the burden of NoV outbreaks in military populations.

References

- Division of Viral Diseases, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated norovirus outbreak management and disease prevention guidelines. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2011;60(RR-3):1–18.

- Delacour H, Dubrous P, Koeck JL. Noroviruses: a challenge for military forces. J R Army Med Corps. 2010;156(4):251–254.

- Queiros-Reis L, Lopes-João A, Mesquita JR, Penha-Goncalves C, Nascimento MSJ. Norovirus gastroenteritis outbreaks in military units: a systematic review [published online ahead of print 13 May 2020]. BMJ Mil Health.

- Glass RI, Parashar UD, Estes MK. Norovirus gastroenteritis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(18):1776–1785.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center. Historical perspective: norovirus gastroenteritis outbreaks in military forces. MSMR. 2011;18(11):7–8.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Surveillance snapshot: Norovirus outbreaks among military forces, 2008–2016. MSMR. 2017;24(7):30–31.

- Lopes-João A, Mesquita JR, de Sousa R, Oleastro M, Penha-Gonçalves C, Nascimento MSJ. Acute gastroenteritis outbreak associated to norovirus GI.9 in a Portuguese army base. J Med Virol. 2017;89(5):922–925.

- Neo FJX, Loh JJP, Ting P, et al. Outbreak of caliciviruses in the Singapore military, 2015. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):719.

- Lopes-João A, Mesquita JR, de Sousa R, et al. Country-wide surveillance of norovirus outbreaks in the Portuguese Army, 2015–2017. J R Army Med Corps. 2018;164(6):419–422.

- Watier-Grillot S, Boni M, Tong C, et al. Challenging investigation of a norovirus foodborne disease outbreak during a military deployment in Central African Republic. Food Environ Virol. 2017;9(4):498–501.

- Sanchez MA, Corcostégui SP, De Broucker CA, et al. Norovirus GII.17 outbreak linked to an infected post-symptomatic food worker in a French military unit located in France. Food Environ Virol. 2017;9(2):234–237.

- Lopes-João A, Mesquita JR, de Sousa R, Oleastro M, Penha-Gonçalves C, Nascimento MSJ. Simultaneous norovirus outbreak in three Portuguese army bases in the Lisbon region, Dec. 2017 [published online ahead of print 4 July 2019]. J R Army Med Corps. 2019;jramc-2019-001242.

- Kebisek J, Richards EE, Buckelew V, Hourihan MK, Finder S, Ambrose JF. Norovirus outbreak in Army service members, Camp Arifjan, Kuwait, May 2018. MSMR. 2019;26(6):8–13.

- Thompson J. More than 100 norovirus cases at Hurlburt. North West Florida Daily News. 16 Dec. 2017. https://www.nwfdailynews.com/news/20171216/more-than-100-norovirus-cases-at-hurlburt. Accessed 12 April 2020.

- Roeder T. Hundreds of Air Force Academy cadets sickened in norovirus outbreak. Colorado Springs Gazette. 20 Nov. 2019. https://gazette.com/military/hundreds-of-air-forceacademy-cadets-sickened-in-norovirus-outbreak/article_118b372a-0be7-11ea-8384-6f631e8afc31.html. Accessed 19 April 2020.

- Brooks KM, Zeighami R, Hansen CJ, McCaffrey RL, Graf PCF, Myers CA. Surveillance for norovirus and enteric bacterial pathogens as etiologies of acute gastroenteritis at U.S. military recruit training centers, 2011–2016. MSMR. 2018;25(8):8–12.