What Are the New Findings?

The crude annual incidence rates of any chronic pain diagnoses in the military increased steadily over the past decade, as has the associated burden of these conditions. Current findings also showed that the overall rates of chronic pain diagnoses varied by demographic and military characteristics.

What Is the Impact on Readiness and Force Health Protection?

Chronic pain negatively impacts the ability of service members to perform their duties and limits their readiness. By understanding the burden of chronic pain and recognizing that its upward trend will likely continue, the Department of Defense may better allocate resources to combat chronic pain from a population-based perspective that focuses on prevention and mitigation.

Abstract

In the annual Medical Surveillance Monthly Report (MSMR) burden of disease analysis, neurologic disorders represent the fifth most common category of diagnoses among active component service members within the Military Health System. One major subcategory of this disease group is "all other neurologic conditions." Incidence analysis from 2009–2018 revealed that the vast majority of diagnoses in this undefined subcategory were related to chronic pain and that such diagnoses have been increasing in burden by a considerable amount. Chronic pain diagnoses increased from a rate of 85.5 per 10,000 person-years (p-yrs) in 2009 to 261.1 per 10,000 p-yrs in 2018. Subgroup analysis by demographic characteristics demonstrated that female, non-Hispanic black, older, and enlisted personnel were at increased risk for chronic pain diagnoses. Among the branches of service, members of the Army were at the highest risk of a chronic pain diagnosis with a rate ratio of 4.8 compared to the Navy, the branch with the lowest risk. Future annual burden analyses should consider chronic pain as its own subcategory to better characterize its impact.

Background

Neurologic disorders are diseases of the central and peripheral nervous systems. In the past 5 annual burden of disease issues of the Medical Surveillance Monthly Report (MSMR), the major category "neurologic conditions" accounted for the fifth largest proportion of medical encounters among active component service members. In brief, these burden analyses classified healthcare encounters (outpatient visits and hospitalizations) by the primary (first-listed) diagnoses, which are subsequently grouped into 142 burden of disease-related conditions and 25 major categories based on a modified version of the classification system developed for the Global Burden of Disease Study.1 Since 2016, these diagnoses have been recorded using International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes. In 2018, the neurologic conditions category accounted for over 680,000 medical encounters among active component service members.2

The neurologic conditions category consists of 6 burden-related conditions, which include organic sleep disorders, "all other neurologic conditions", other mononeuritis, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, and Parkinson disease. In 2018, organic sleep disorders accounted for the most medical encounters among active component service members followed by "all other neurologic conditions." The latter grouping accounted for 113,050 medical encounters, affected 39,433 individuals, and was responsible for 3,046 bed days.2

Identifying the specific conditions that contribute to the burden of the disease-related condition category "all other neurologic conditions" would help to clarify the overarching composition of the burden of neurologic conditions within the military. A 2011 MSMR analysis evaluated the diagnostic codes associated with an observed increase in outpatient encounters for neurologic disorders among active component service members during 2005–2010.3 This analysis demonstrated that chronic pain conditions accounted for a sizable proportion of the outpatient encounters within the "all other neurologic conditions" category. In addition, the rates of incident medical encounters with a primary diagnosis related to chronic pain among active component military members increased substantially from 2007 through 2014.4

This report summarizes the types of conditions included in the subcategory "all other neurologic conditions" at the 3-digit ICD code level, describes the temporal trends in the morbidity burden of these conditions, and examines the relative proportion of diagnoses in this category contributed by chronic pain diagnoses without a specific etiology (i.e., chronic pain diagnoses not attributed to trauma or a surgical or other procedure). Lastly, the current analysis updates the prior MSMR report on the incidence of chronic pain diagnoses among active component military members4 and describes trends in the annual incidence rates of these chronic pain diagnoses in this population during 2009–2018.

Methods

The surveillance population for this retrospective cohort study included all service members who served in the active component of the U.S. Army, Navy, Air Force, or Marine Corps at any point during the interval from 1 Jan. 2009 through 31 Dec. 2018. This analysis used data available from the Defense Medical Surveillance System (DMSS). The DMSS, maintained by the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch, contains longitudinal data on service members, including medical encounter records and demographic data. Diagnoses were ascertained from the administrative records of all medical encounters of individuals who received care in military medical treatment facilities, civilian facilities in the Click to closePurchased CareThe TRICARE Health Program is often referred to as purchased care. It is the services we “purchase” through the managed care support contracts.purchased care system, or in deployed settings as documented in the Theater Medical Data Store.

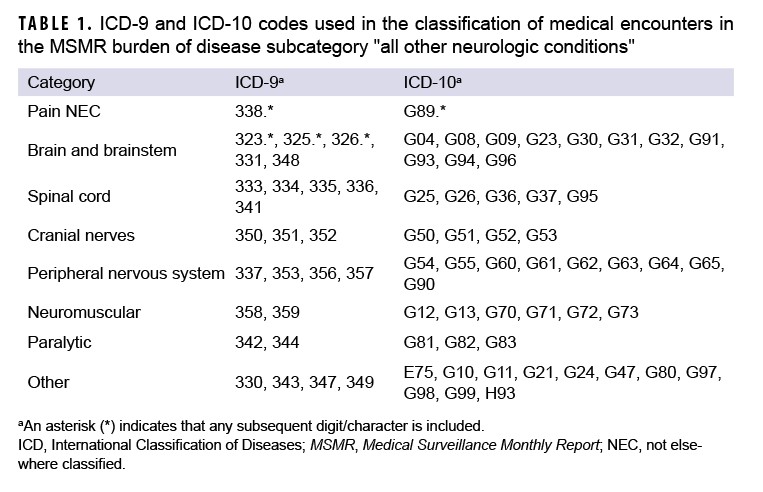

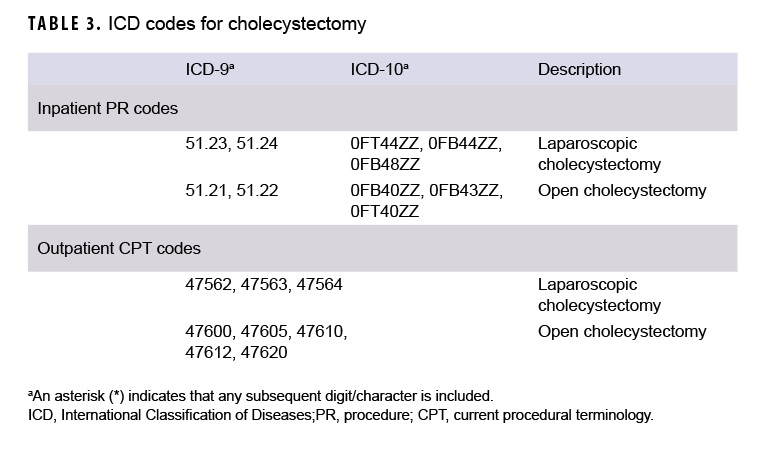

For the period between 2009 and 2018, all medical encounters were identified for which the primary listed diagnosis would have resulted in classification into the "all other neurologic conditions" subcategory of the annual MSMR burden analysis.2 In the burden analysis, ICD codes for pain that specify an etiology (e.g., chronic postthoracotomy pain, chronic pain due to trauma) are classified into relevant condition subcategories and not the "all other neurologic conditions" subcategory. Medical encounters in the "all other neurologic conditions" subcategory were then further classified into 8 distinct and mutually exclusive subgroups based on conceptual organization and the disease conditions represented (Table 1). These subgroups included pain not elsewhere classified (NEC), brain and brainstem, spinal cord, cranial nerves, peripheral nervous system, neuromuscular, paralytic, and "other". This initial classification schema provided a summary of diagnoses at the 3-digit ICD code level. For example, the pain NEC subgroup included both acute and chronic pain diagnoses that were not attributed to a specific etiology (ICD-9: 338.*; ICD-10: G89.*). In a more specific example, "other chronic pain" is represented by ICD-9 diagnosis code 338.29 and ICD-10 code G89.29. The ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes included in each subgroup are listed in Table 1. The numbers of medical encounters attributed to and individuals affected by diagnoses in each of the 8 subgroups were examined over time. Chronic pain-specific diagnoses were identified from within the subgroup of pain NEC diagnoses to determine the relative percentage of diagnoses attributable to chronic pain.

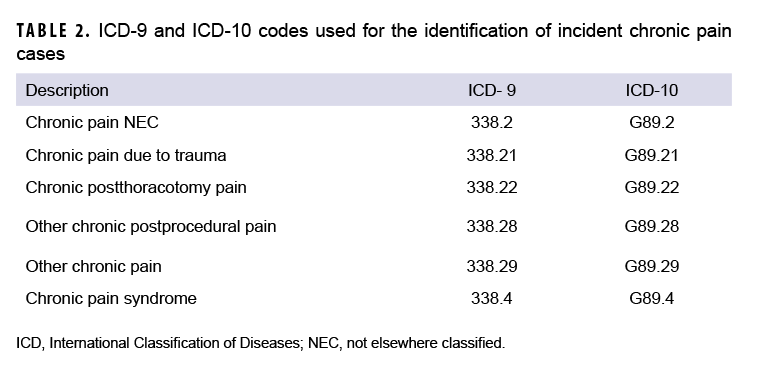

A second analysis was carried out in which the overall incidence of any chronic pain-specific diagnoses was calculated and examined by demographic and military characteristics. For this analysis, an incident case of chronic pain was defined as any inpatient or outpatient encounter with 1 of the qualifying chronic pain codes (Table 2) listed in the primary or secondary diagnostic position. An individual could only be counted as an incident case once during the surveillance period. The current analysis incorporated additional chronic pain diagnoses that were not included in the prior burden analysis, such as those attributed to a specific etiology. Annual incidence rates of any chronic pain diagnoses as well as annual rates of 6 types of chronic pain diagnoses were examined. The types of chronic pain diagnoses included chronic pain NEC, chronic pain due to trauma, chronic post-thoracotomy pain, other chronic post-procedural pain, other chronic pain, and chronic pain syndrome. Overall and annual rates of any incident chronic pain diagnoses were calculated per 10,000 person-years (p-yrs) of active component service. Annual rates of the 6 types of chronic pain-specific diagnoses were calculated in the same manner. In addition, the total number of chronic pain-related encounters was determined and used to compute the average number of encounters per affected individual. All statistical analyses were carried out using SAS/STAT software, version 9.4 (2014, SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Burden

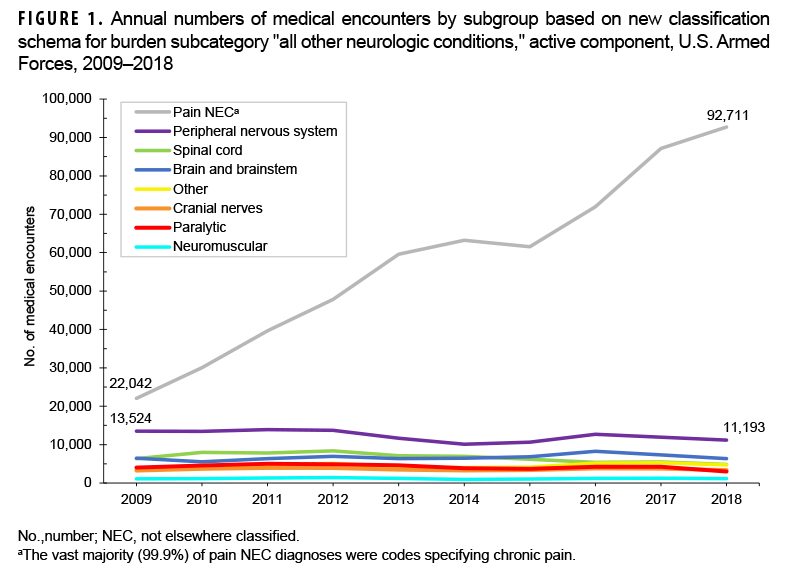

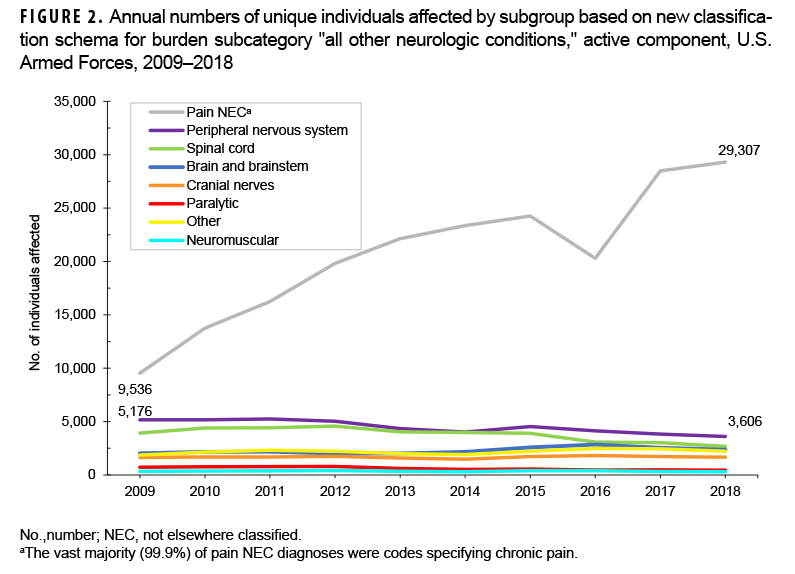

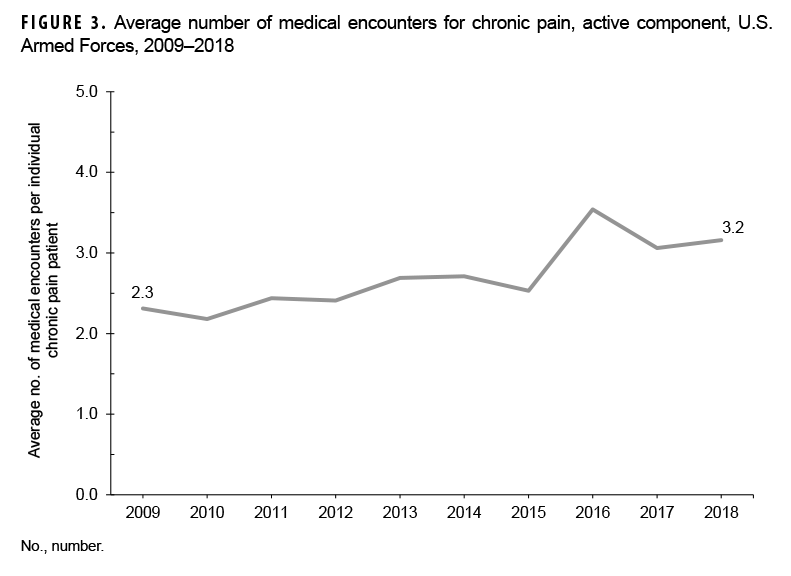

In 2018, diagnoses falling under the ICD-9/ICD-10 parent code pain NEC accounted for 79.1% (92,711/117,279) of the medical encounters related to and 73.5% (29,307/39,896) of the individuals affected by conditions within the "all other neurologic conditions" burden subcategory (Figure 1, 2). Although this group of codes included both acute and chronic pain diagnoses, almost all (99.9%) of the diagnoses were codes specifying chronic pain (data not shown). As such, references to pain NEC can hereafter be interpreted as "chronic pain". Over the 10-year period, the number of medical encounters attributed to and individuals affected by diagnoses of pain NEC increased from 22,042 to 92,711 and 9,536 to 29,307, for increases of 320.6% and 207.3%, respectively (Figures 1, 2). Moreover, the number of medical encounters per patient with chronic pain rose steadily from 2.3 in 2009 to 3.2 in 2018 (Figure 3). In contrast, the number of medical encounters related to and individuals affected by diagnoses within the other 7 subgroups remained relatively stable from 2009 through 2018, with comparatively minor fluctuations in counts. (Figures 1, 2).

Incidence

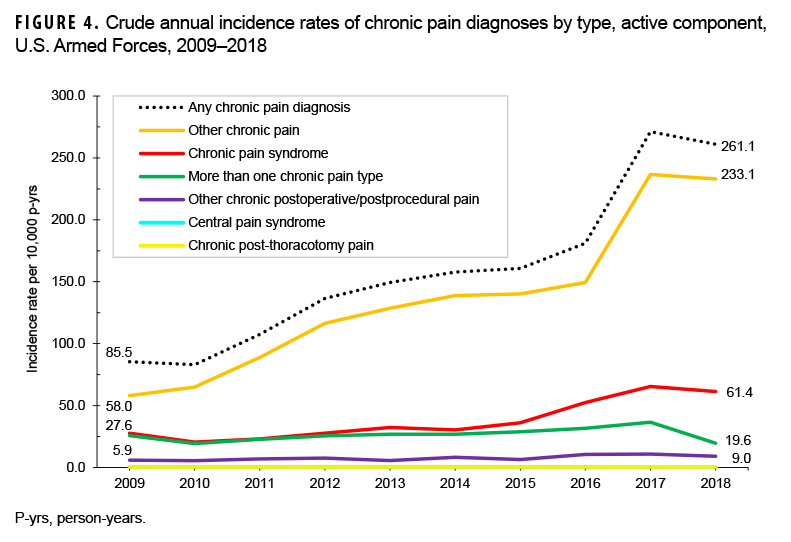

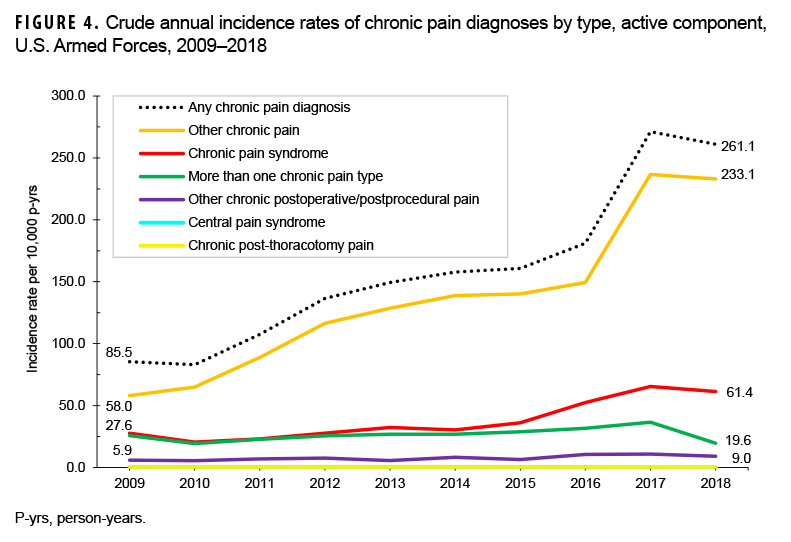

Between 2009 and 2018, 212,480 service members received an incident chronic pain diagnosis (Table 3). The most frequent chronic pain diagnosis was "other chronic pain." This diagnosis represented 85.0% of incident chronic pain diagnoses during the 10-year surveillance period (data not shown). In addition, approximately 1 in 6 service members who qualified as an incident chronic pain case received more than 1 diagnosis of the chronic pain types examined in this analysis (data not shown). The crude incidence rate of any chronic pain diagnoses increased from 85.5 per 10,000 p-yrs in 2009 to 261.1 per 10,000 p-yrs in 2018 (Figure 4). This trend was largely driven by increases in the rates of incident diagnoses of "other chronic pain,", which increased from 58.0 per 10,000 p-yrs in 2009 to 233.1 per 10,000 p-yrs in 2018 (Figure 4).

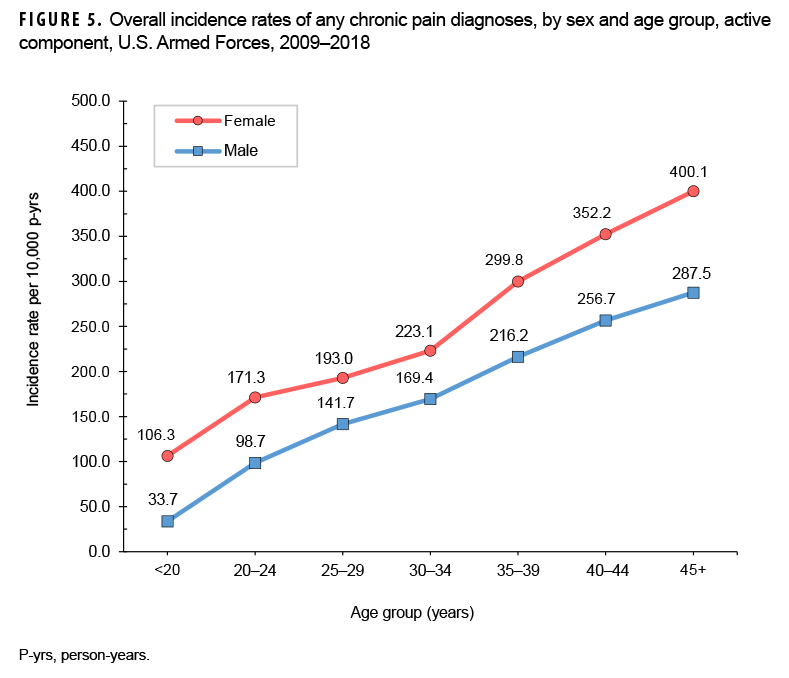

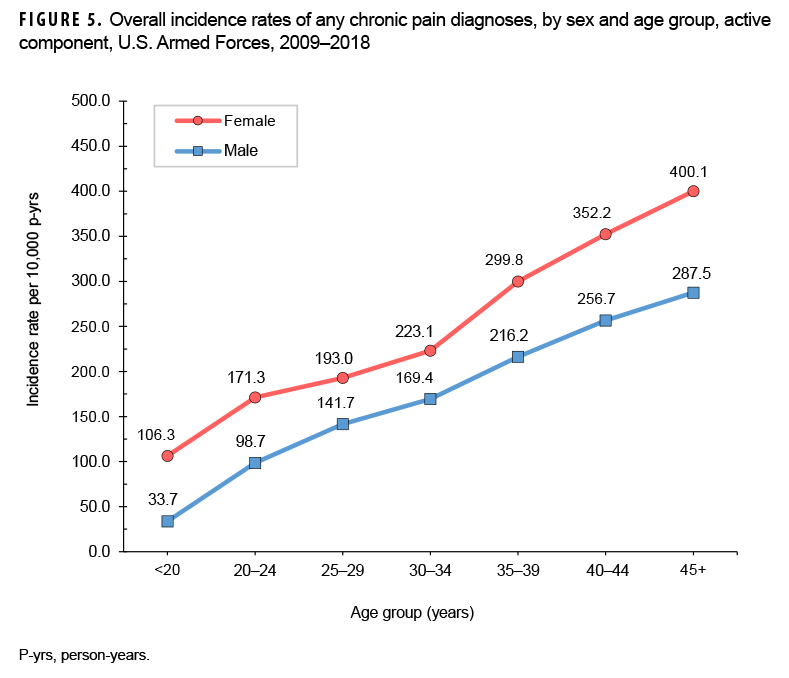

During the 10-year surveillance period, males received 79.7% (n=169,423) of incident chronic pain diagnoses during the surveillance period; however, the overall rate of chronic pain diagnoses in females was 1.4 times that of their male counterparts (211.0 cases per 10,000 p-yrs versus 147.8 cases per 10,000 p-yrs, respectively) (Table 3). In both sexes, the overall rate of any incident chronic pain diagnoses increased with increasing age (Figure 5). The elevated incidence rate of any chronic pain diagnoses in females was evident across all age groups but the largest rate differences by sex were among the 3 oldest age groups. Across race/ethnicity groups, the overall rate was highest among non-Hispanic black service members (191.9 per 10,000 p-yrs) and lowest among those of other/unknown race/ethnicity (123.8 per 10,000 p-yrs) (Table 3). The overall rate among non-Hispanic black service members was 1.2 times that of non-Hispanic white service members.

Service members in the U.S. Army had the highest overall incidence rate of chronic pain diagnoses as compared to their counterparts in other services (Table 3). The overall rate of incident chronic pain diagnoses among Army members was 4.8 times that among Navy members (284.7 and 59.2 per 10,000 p-yrs, respectively). The overall rates among Air Force members and Marine Corps members were 94.5 and 85.6 per 10,000 p-yrs, respectively (Table 3). Overall incidence rates of chronic pain diagnoses were highest among senior enlisted service members (220.3 per 10,000 p-yrs) and lowest among junior officers (108.3 per 10,000 p-yrs) (Table 3).

Editorial Comment

This analysis revealed a marked increase in the crude annual incidence rates of any chronic pain diagnoses, the numbers of chronic pain-related encounters, and the numbers of unique individuals affected by chronic pain during 2009–2018. The vast majority of encounters (79.1%) and individual patients (73.5%) associated with the burden subcategory "all other neurologic conditions" were attributable to diagnoses of chronic pain. In addition, chronic pain diagnoses were the only subgroup of diagnoses in this subcategory that demonstrated a steady and increasing trend in crude incidence rates over the 10-year period. It is uncertain whether this trend of crude rates of chronic pain diagnoses represents a true increase in the experience of chronic pain across the military over the course of the surveillance period, a change in diagnostic guidelines or methodologies, heightened awareness and acceptance for reporting chronic pain by patients, the expansion of integrated interdisciplinary pain management teams, or some other factors. However, it is notable that this increase in chronic pain diagnoses is not restricted to military populations; these trends have been documented in civilian populations in both the U.S. and globally.5–7 The existence of similar patterns in other contexts suggests that the increases seen in this analysis reflect true increases in chronic pain. Further, not only are there increasing rates of chronic pain encounters and individuals affected by chronic pain, but the mean number of encounters per chronic pain patient also increased during the surveillance period. This increasing trend of healthcare utilization related to chronic pain has also been noted in U.S. civilian populations in patients with back pain.8,9

There were pronounced differences in the overall incidence of any chronic pain diagnosis by demographic characteristics as well, though they were all generally reflective of findings noted in U.S. civilian populations. With respect to sex, females were at higher risk of having a chronic pain diagnosis than men, which is well documented in civilian populations.10 Although research on the causes of this difference is still underway, it is likely due to a combination of physiologic differences, societal conditioning, differences in healthcare interactions, and other possible factors. There was also a linear trend in the increase of rates of chronic pain diagnoses with age, a pattern that has been similarly noted in civilian literature.5 This pattern is due to greater "wear and tear" on service members' bodies, more opportunities for some trauma to occur or medical conditions associated with pain to arise, and physiologic changes associated with aging. There were also notable differences by race/ethnicity group, with non-Hispanic black service members at higher risk of a chronic pain diagnosis compared to those in other race/ethnicity groups, as has been observed in U.S. civilian populations.11

Finally, notable differences in overall rates of incident chronic pain diagnoses were also observed by service; Army members had a much higher overall rate of chronic pain than members of any of the other services. There is no clear explanation for these differences. However, some contributing factors may include the Army imposing a greater institutional focus on pain management and chronic pain identification, demographic differences across the services (e.g., age and sex), and differences in physical training methodologies. There were also differences in the overall rates between junior versus senior grades as well as enlisted personnel versus officers. The differences between enlisted and officers is likely due to the composition of their military duties, with enlisted personnel performing more physically burdensome and potentially harmful activities compared to their officer peers. The junior vs senior grade differences likely reflect the impact of age, as senior service members are more likely to be older and therefore at higher risk of chronic pain. Observed differences in overall rates of incident chronic pain diagnoses warrant further examination of adjusted (e.g., by age, sex, race/ethnicity) incidence rates among service members.

Performing surveillance epidemiology of this sort is critical, as an understanding of disease baseline rates, temporal trends, and demographic composition is vital for attempts to control chronic pain through clinical and public health measures. Management of neurologic conditions from preventive and readiness standpoints requires an understanding of the associated risk factors. Further, by examining the burden of chronic pain and recognizing that its marked upward trend will likely continue, the Department of Defense may better allocate resources to combat chronic pain from a population-based perspective with focuses on prevention and mitigation.

Author Affiliations: Department of Preventive Medicine and Biostatistics, Uniformed Services University (CPT Smith); Defense Health Agency, Armed Force Health Surveillance Branch (Dr. Taubman and Dr. Clark).

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank Dr. Tracey Beason-Serafica, CDR Shawn Clausen, Dr. Shauna Stahlman, and Dr. Clara Ziadeh of the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch for their valuable input throughout the project.

Disclaimer: The contents, views, or opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect official policy or position of Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, the Department of Defense, or Departments of the Army, Navy, or Air Force. Mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

References

- Murray CJL, Lopez AD, eds. The Global Burden of Disease: A Comprehensive Assessment of Mortality and Disability from Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors in 1990 and Projected to 2020. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1996:120–122.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Absolute and relative morbidity burdens attributable to various illnesses and injuries, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2018. MSMR. 2019;26(5):2–10.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center. Relationships between increasing outpatient encounters for neurological disorders and introductions of associated diagnostic codes, active duty military service members, 1998–2010. MSMR. 2011;18(10):2–8.

- Clark LL, Taubman SB. Incidence of diagnoses using ICD-9 codes specifying chronic pain (not neoplasm related) in the primary diagnostic position, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2007–2014. MSMR. 2015;22(12):12–15.

- Dahlhamer J, Lucas J, Zelaya C, et al. Prevalence of chronic pain and high-impact chronic pain among adults–United States, 2016. Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1001–1006.

- Mills, SEE, Nicolson KP, Smith BH. Chronic pain: a review of its epidemiology and associated factors in population-based studies. Br J Anaesth. 2019;123(2):e273–e284.

- Pitcher MH, Von Korff M, Bushnell MC, et al. Prevalence and profile of high-impact chronic pain in the United States. J Pain. 2019;20(2):146–160.

- Gaskin DJ, Richard P. The economic costs of pain in the United States. J Pain. 2012;13(8): 715–724.

- Thorpe KE, Florence CS, Joski P. Which medical conditions account for the rise in health care spending? Health Affairs. 2004; W4-437–W4-445.

- Bartley EJ, Fillingim RB. Sex differences in pain: a brief review of clinical and experimental findings. Br J Anaesth. 2013;111(1):52–58.

- Campbell CM, Edwards RR. Ethnic differences in pain and pain management. Pain Manag. 2012;2(3):219–230.