What Are the New Findings?

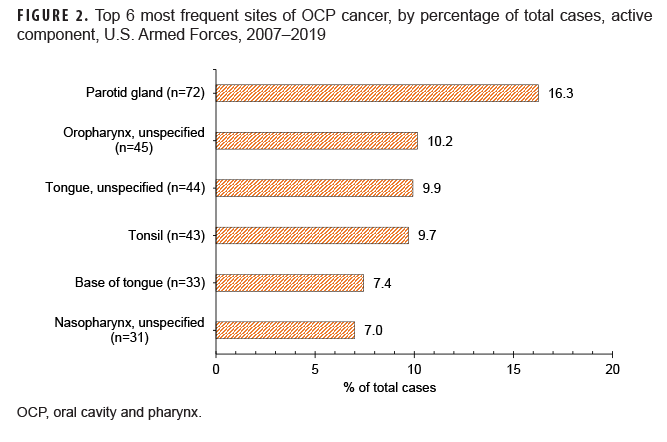

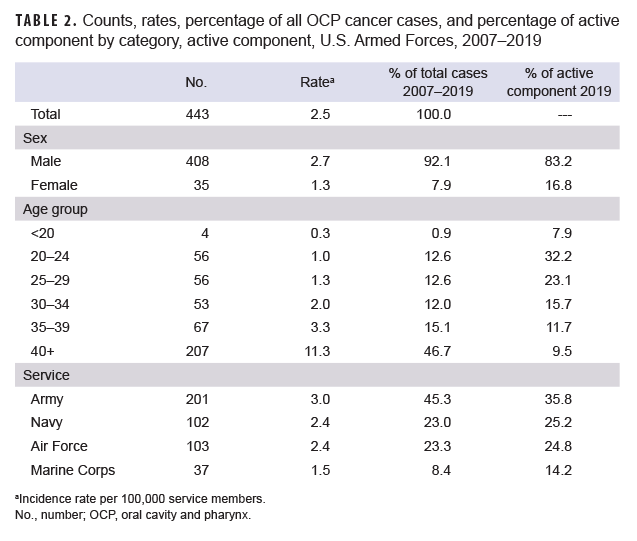

There were 443 cases of OCP cancer among active component service members from 2007 through 2019. Rates increased with advancing age. The Army had the greatest number of cases (n=201), as well as the highest 13- year incidence rate (3.0 per 100,000 service members); the Marine Corps had the lowest incidence rate (1.5 per 100,000 service members). The most common site of OCP cancer was the parotid gland (n=72).

What Is the Impact on Readiness and Force Health Protection?

OCP cancer often progresses with little to no pain or symptoms in the beginning, and is not discovered until it has metastasized to another location. These cancers may be accompanied by severe esthetic and debilitating functional complications, as well as a poor prognosis, thereby threatening service member readiness.

Abstract

The purpose of this study was to determine the incidence of oral cavity and pharynx (OCP) cancer among service members in the active component military (i.e., Army, Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps) from 2007 through 2019, and to provide an overview of the rates and trends throughout this period. There were 443 cases of oral cavity and pharynx cancer in the active component during those 13 years. The overall male incidence rate (2.7 per 100,000 service members) was greater than the female incidence rate (1.3 per 100,000 service members). Service members 40 years or older had the highest overall incidence rate (11.3 per 100,000 service members) which was 3.4 times the next highest rate (3.3 per 100,000 service members) observed among those aged 35–39. The Army had the greatest number of cases (n=201) followed by the Air Force (n=103), Navy (n=102), and Marine Corps (n=37). The Army had the highest overall 13-year incidence rate (3.0 per 100,000 service members) when compared to the Air Force (2.4 per 100,000 service members), Navy (2.4 per 100,000 service members), and Marine Corps (1.5 per 100,000 service members). By anatomical location, cancer of the parotid gland accounted for the highest percentage of cases (16.3%).

Background

Oral cavity and pharynx (OCP) cancers are known collectively as head and neck cancers1–4 and represent 2.9% of all new cancer cases in the U.S.2 Among the estimated 53,260 new cases of OCP cancer in the U.S. in 2020, roughly half will survive 5 years.1,2 Men are twice as likely as women to be diagnosed with OCP cancer,1,2 and it is most common among those aged 55 to 64.1,2,4 OCP cancer is not very common compared to other forms of cancer; however, the OCP-related death rate is particularly high because it is usually not discovered until late in its development.1,2

Almost all OCP cancers begin in the thin, flat squamous cells of the mouth.1–3 The oral cavity includes the lip, floor of the mouth, salivary glands, and other sites such as the palate, buccal mucosa, alveolar ridges, anterior two-thirds of the tongue, and retromolar trigone (the area behind the last mandibular molars).1–3 The pharynx includes the nasopharynx, oropharynx, and hypopharynx.1–3 Surveillance reports tend to present data on cancers of the salivary gland, nasopharynx, and hypopharynx separately from those of the other sites listed previously because they are etiologically and biologically distinct and may present with different prognoses and treatment options.1–4 In order to provide a broad overview of OCP cancer in the active component service member population, cancer of any site anatomically located in the oral cavity or pharynx was included in this report.

OCP cancer is an extremely troubling form of cancer because it can be overlooked easily in its early stages.1,5 It often progresses with little to no pain or symptoms in the beginning and is not discovered until it has metastasized to another location, usually the lymph nodes of the neck.1,5 In addition, head and neck cancers have a high risk of producing a second primary tumor, usually in the lungs, esophagus, neck, or head.1

The most common risk factors for OCP cancer include a history of combustible or smokeless tobacco product use, heavy alcohol consumption, and infection with human papillomavirus (HPV).1,6,7 HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection in the U.S. and can spread through direct sexual contact to genital areas as well as the mouth and throat;7 virtually all sexually active men and women will be infected with at least 1 type of HPV during their lifetimes.8 It is estimated that HPV causes 70% of oropharyngeal cancers in the U.S.7

Examples of signs and symptoms of OCP cancer in its earlier stages include sudden tooth mobility, pain, unusual oral bleeding, persistent red and/or white patches inside the mouth, non-healing oral ulcers, and unusual intraoral surface changes.9,10 In the later stages of OCP cancer, a patient might experience airway obstruction, paresthesia (tingling, prickling, or burning sensation), altered vision, hardened areas, numbness, persistent pain, swollen lymph nodes in the neck, or referred pain.9,10

The stage of OCP cancer at diagnosis refers to the extent of the disease, which is associated with the 5-year survival rate.2 OCP cancer is characterized by 3 stages, localized, regional, and distant.2 If the stage is determined to be regional or distant, the cancer has spread to another location of the body.2 Localized OCP cancer has the highest 5-year survival rate of 85.1%, regional 66.8%, and distant 40.1%.2

The approach to treatment of OCP cancer is usually a combination of surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy, which will vary from patient to patient.11,12 When OCP cancer is not detected until a later stage, treatment may result in severe complications which can impact both function and esthetics. Some complications include infection, pain, bleeding, and muscle damage, as well as difficulty speaking, breathing, and swallowing.1,2,9 Any disease capable of causing such impairment has the potential to threaten military readiness and should be monitored. The purpose of this report is to determine the incidence of OCP cancer among active component service members from 2007 through 2019 and to provide an overview of the rates and trends of these cancers throughout the study period.

Methods

The U.S. Army Public Health Center (APHC) Public Health Review Board approved this study. It was assigned project #18-676 under the Disease Epidemiology Program Umbrella Plan. The data presented were obtained from the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Division, which manages the Defense Medical Surveillance System (DMSS). The DMSS is the central repository of medical surveillance data for the U.S. Armed Forces. It contains current and historical data on diseases and medical events, as well as longitudinal data on personnel and deployments.

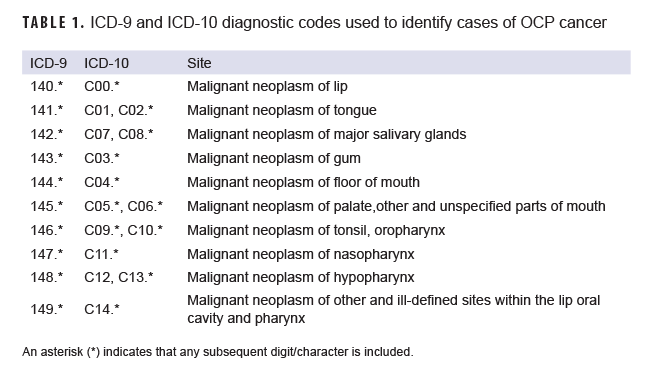

This investigation obtained and analyzed data on active component service members of the Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps for the years 2007 through 2019. Diagnoses were classified using the International Classification of Diseases, 9th and 10th Revisions (ICD-9 and ICD10) (Table 1). For surveillance purposes, a case of OCP cancer was defined as: 1) one hospitalization with any of the defining diagnoses of OCP cancer in the primary diagnostic position; or 2) one hospitalization with a Z- or V-code indicating a radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or immunotherapy treatment procedure in the primary diagnostic position; and any of the defining diagnoses of OCP cancer in the secondary diagnostic position; or 3) three or more outpatient medical encounters, occurring within a 90-day period, with any of the defining diagnoses of OCP cancer in the primary or secondary diagnostic position. The incidence date was the date of the first qualifying hospitalization or outpatient medical encounter that included a diagnosis of OCP cancer. An individual was considered an incident case only once per lifetime. Additional variables employed in the analysis included year of diagnosis, age at diagnosis, rank, military service, and sex. Annual incidence rates were calculated for each service by dividing the number of OCP cancer cases by the number of active component service members reported in the Defense Medical Epidemiology Database (DMED) for that particular service and year.

Results

There were 443 cases of OCP cancer among active component service members from 2007 through 2019, for a crude overall incidence rate of 2.5 per 100,000 service members (Table 2). Overall, the number of OCP cancer cases (n=408) and the incidence rate (2.7 per 100,000 service members) among male service members exceeded that among female service members (n=35 and 1.3 per 100,000 service members, respectively). Male service members accounted for 92.1% of all cases during the study period and, as of 2019, 83.2% of the active component. The largest proportion of all cases (46.7%) occurred among active component service members 40 years or older; in 2019, this age group made up only 9.5% of the active component. Service members 40 years or older had the highest 13-year rate of incident OCP cancer (11.3 per 100,000 service members) which was 3.4 times the next highest rate (3.3 per 100,000 service members) observed among service members 35–39 years of age. The greatest number of cases was in the Army (n=201) followed by the Air Force (n=103), Navy (n=102), and the Marine Corps (n=37). The Army constitutes the greatest proportion of the active component (35.8% in 2019), and made up an even greater proportion of all cases (45.3%) during the 13-year study period. Similarly, the Marine Corps constitutes the smallest proportion of the active component (14.2% in 2019), and made up the smallest proportion of all cases (8.4%). The Army had the highest overall 13-year incidence rate of OCP cancer (3.0 per 100,000 service members), followed by the Air Force (2.4 per 100,000 service members), the Navy (2.4 per 100,000 service members), and the Marine Corps (1.5 per 100,000 service members) (Table 2).

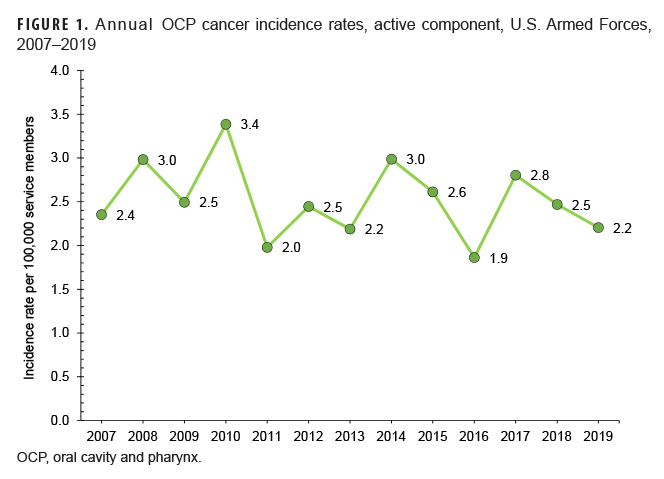

During 2007 through 2019, crude annual rates of incident OCP cancer fluctuated between 1.9 per 100,000 service members and 3.4 per 100,000 service members (Figure 1). Small case counts precluded the examination of trends over time by sex.

The majority of all cases (60.5%) occurred in the following 6 sites: parotid gland, oropharynx (unspecified), tongue (unspecified), tonsil, base of tongue, and nasopharynx (unspecified). The greatest number of cases (n=72; 16.3%) occurred in the parotid gland (Figure 2).

Editorial Comment

This study used surveillance data to estimate the incidence of OCP cancer in the active component military from 2007 through 2019. Previously, this group of cancers had not been investigated by the APHC.

Men in the U.S. general population are known to be at a greater risk of developing OCP cancer than women; the same pattern was apparent for the active component. The vast majority of the OCP cancer cases (92.1%) were among male service members and the rate of incident OCP cancer among male service members was twice that of female service members.

In the U.S. general population, OCP cancer is most frequently diagnosed among those aged 55 to 64.2 Service members 40 years or older made up the smallest proportion of the active component (9.5% in 2019), yet out of the 6 age groups observed in this study, this category contained the greatest proportion of cases (46.7%) and the highest incidence rates per 100,000 service members.

Given the size distribution of the services, the distribution of cases among them throughout the study period was as expected. The greatest proportion of cases was among Army members (45.3%); the smallest proportion of cases was among Marine Corps members (8.4%).

Incidence rates per 100,000 service members were calculated for each service by year to compare risk between the services. Although these populations differ by size, they share similarities in sex distribution, diet, physical fitness, access to health care, etc. Nevertheless, there still seems to be an OCP cancer disparity between the services. The Army had the highest overall 13-year incidence rate which was 2.1 times that of the Marine Corps, 1.3 times the Navy rate, and 1.2 times the Air Force incidence rate. This finding may be explained by the differing age distributions of the services. Active component service members 40 years or older constituted the greatest proportion of cases (46.7%) and their risk of diagnosis was more than 3.4 times that of any other age group. The percentage of Army service members in the 40 years or older age group (9.1%) exceeded that of the Navy (8.6%), Air Force (7.4%), and Marine Corps (3.9%) (data not shown).

The higher incidence of OCP cancer among Army members may also be due to dissimilar contributing risk factors across the services (e.g., tobacco use, alcohol use, HPV infection). However, according to the 2015 Department of Defense Health Related Behaviors Survey (HRBS), use of all types of tobacco products was more common among Marine Corps service members than among members of any other service; such use was least common among members of the Air Force.13 Incidence rates of OCP in the Marine Corps may be higher if service members remained in service comparatively as long as the Army (and therefore, were older in age).

The primary limitation of this study was the use of de-identified data. Names, social security numbers, etc. did not accompany the case list provided by AFHSD. Therefore, linking individual risk factors available in alternate databases was not possible. Another limitation was the small number of cases of OCP cancers. Rates based on such small case counts are unstable, which precluded the examination of trends over time by service or sex. Additionally, when compared to other health conditions among active component service members, OCP cancer accounts for an extremely small percentage of the overall disease burden.

Although this study did examine demographic risk factors of OCP cancer, it did not examine those lifestyle factors that are well known (i.e., tobacco use, alcohol abuse, and HPV infection). Because these risk factors are modifiable, behavior changes may play a significant role in decreasing risk. Dental providers, as well as service members themselves, contribute considerably to the prevention and detection of OCP cancer. Yearly dental examinations provide dentists with an opportunity to assess service members' risk of OCP cancer. However, given the importance of early detection, it is highly recommended that service members conduct their own monthly self-screenings—a process of examining one's own mouth for any signs of oral cancer.

Author Affiliations: U.S. Army Public Health Center, Disease Epidemiology Branch, Aberdeen Proving Ground, MD, U.S. (MAJ Goodwin).

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense, Department of the Army, or the U.S. Government.

- The Oral Cancer Foundation. Oral cancer facts. https://oralcancerfoundation.org/facts/. Accessed 20 August 2020.

- The National Cancer Institute, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer stat facts: oral cavity and pharynx cancer. Accessed 20 August 2020. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/oralcav.html

- American Cancer Society. What are oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancers? Accessed 20 August 2020. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/oral-cavity-and-oropharyngeal-cancer/about/what-is-oral-cavity-cancer.html

- The National Cancer Institute. Cancers by body location/system. Accessed 20 August 2020. https://www.cancer.gov/types/by-body-location

- American Cancer Society. Can oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancers be found early? Accessed 24 August 2020. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/oral-cavity-and-oropharyngeal-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/detection.html

- The National Cancer Institute, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Lip and oral cavity cancer treatment. Accessed 24 August 2020. https://www.cancer.gov/types/head-and-neck/patient/adult/lip-mouth-treatment-pdq#_1

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HPV and oropharyngeal cancer. Accessed 24 August 2020.https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/basic_info/hpv_oropharyngeal.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About HPV. Accessed 24 August 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/parents/about-hpv.html

- The Oral Cancer Foundation. Early detection, diagnosis, and staging. Accessed 24 August 2020. https://oralcancerfoundation.org/cdc/early-detection-diagnosis-staging/

- American Cancer Society. Signs and symptoms of oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancer. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/oral-cavity-and-oropharyngeal-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/signs-symptoms.html. Accessed 24 August 2020.

- The Oral Cancer Foundation. Treatment. Accessed 20 August 2020.https://oralcancerfoundation.org/treatment/

- American Cancer Society. Treating oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancer. Accessed 24 August 2020. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/oral-cavity-and-oropharyngeal-cancer/treating.html

- Meadows S, Engel C, Collins R, et al. 2015 Department of Defense Health Related Behaviors Survey (HRBS). Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2018.