What are the New Findings?

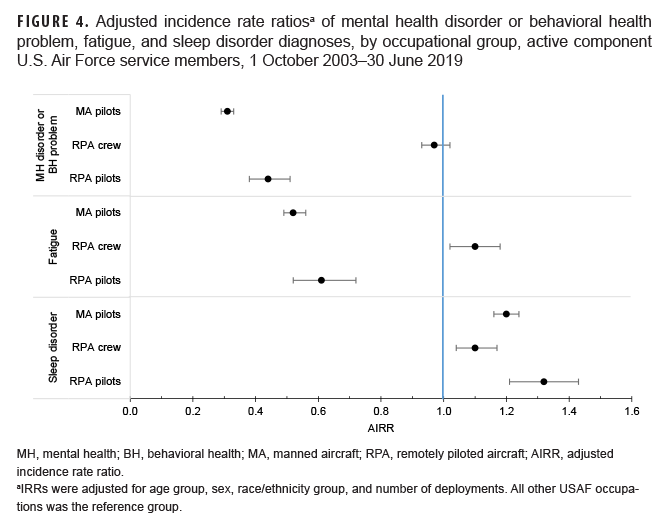

Adjusted incidence rate ratios of MH disorders, BH problems and fatigue were lower among RPA pilots and MA pilots, while fatigue was higher among RPA crew compared to other USAF occupations. All 3 groups had higher risk for sleep disorders compared to other USAF occupations.

What is the Impact on Readiness and Force Health Protection?

Understanding the burden of these outcomes is important for gauging the health of operational USAF members and to help direct actions to reduce and/or prevent the highest risk health concerns. This study can inform leadership's prioritization of resources to maximize pilot and air crew health and readiness.

Abstract

U.S. Air Force (USAF) manned aircraft (MA) pilots and remotely piloted aircraft (RPA) pilots and their non-pilot crew form part of the forward-most contingent of airpower. Limited information exists on the incidence of mental health (MH) disorders, behavioral health (BH) problems, sleep disorders, and fatigue among these groups. Incidence rates and incidence rate ratios of these conditions were calculated among all active component USAF members during the period from 1 October 2003 to 30 June 2019. Compared to those in all other USAF occupations, RPA and MA pilots had statistically significantly lower risk of MH and BH outcomes while RPA crew shared a risk similar to other USAF members, although with higher risk of post-traumatic stress disorder and lower risk of substance- and alcohol-related disorders. This pattern was similar for fatigue outcomes except RPA crew had slightly higher risk. All 3 occupational groups had elevated risk for sleep disorders, and RPA pilots had 32% higher risk compared to those in all other USAF occupations. This study highlights that pilots have lower risk and/or reporting tendency for MH disorders, BH problems, and fatigue, while sleep disorders are common among service members in all of these (RPA/MA pilot, RPA crew) occupations.

Background

In the Department of Defense (DOD), the years from 2002 through 2010 saw an increase of nearly 45-fold (167 to 7,500) in the quantity of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs).1 U.S. Air Force (USAF) remotely piloted aircraft (RPA) have increased from 21 in 2005 to a projected 318 in 2020.2 Operational USAF members, like unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) pilots and their crew members, face dynamic challenges unique to their occupations including mental and social stressors. Recent wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have precipitated a large burden of mental and behavioral health (MH/BH) conditions among U.S. military service members. Although the incidence of MH/BH conditions have decreased slightly since 2007 among all active component service members,3 it is important to conduct surveillance of trends of MH/BH conditions in specific occupational groups which may be at greater risk of these conditions due to operational demands and stressors associated with those occupations.4

The overall decreasing trend in MH/BH conditions among U.S. military personnel may not apply to the RPA community (pilots and the crew [sensor operator and mission intelligence coordinator]). The observed small overall decline in incidence rates of MH/BH conditions may be partially due to decreased deployment activity in Iraq (Operation Iraqi Freedom/OIF, Operation New Dawn/OND) and Afghanistan (Operation Enduring Freedom/OEF) in 2010 and 2014, respectively. However, such decreases in conventional deployed operations may not apply to those RPA pilots and crew who work within a "deployed-in-garrison" setting that involves long hours, shift work, and exposure to traumatic real-time events.5 In fact, the main mission of RPA teams, Combat Air Patrols (CAPs), has increased from 5 CAPs in 2004 to 65 in 2014 and have remained at high levels.6 These CAP missions can and often do operate 24 hours a day every day of the year. Furthermore, beyond elevated rates of MH disorder diagnoses, given their unique occupational setting, RPA teams may also be at greater risk of insomnia, fatigue, and occupational burnout.7 Over 6% of U.S. RPA pilots were noted to meet post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptom criteria.8 Other studies indicate that, in U.K. RPA pilots, the shift-work features of this occupation are among the greatest sources of stress and diminished functional ability.9

Like RPA pilots and crew, manned aircraft (MA) pilots are in a unique occupation compared to many other USAF service members. MA pilots constitute only a fraction of the total USAF but perform a critical mission on the forefront of the operational force. Frequent deployment demands, sometimes reaching a 1:1 combat-to-dwell ratio (the ratio of time deployed to time at home), may pose formidable demands on the MH of these aviators. Related conditions such as fatigue and sleep disorders are also historically common concerns among MA pilots.10

Studies on the incidence of MH/BH and fatigue-related conditions in USAF pilots and crew are limited. In a relevant prior study, Otto and Webber investigated rates of incident MH disorder diagnoses and BH outcomes among MA and RPA pilots in the USAF between Oct. 1, 2003 and Dec. 31, 2011.11 Their findings indicated similar rates of MH disorder diagnoses among MA pilots and their RPA pilot counterparts, both of whom had lower rates than those in other USAF occupations (as designated by Air Force Specialty Code [AFSC]). Changes in the nature of USAF missions since the Otto and Webber study and the ability to include other diagnoses and outcomes (i.e., sleep disorders and fatigue) make the current study a more inclusive characterization of the health risks of this population.

This study describes the demographic and military characteristics of RPA pilots, RPA crew, and MA pilots as well as the incidence rates and rate ratios of MH/BH conditions, sleep disorders, and fatigue among these 3 groups of pilots and crew compared to service members in all other USAF occupations during the surveillance period.

Methods

The surveillance period was Oct. 1, 2003 (the inception date for the RPA pilot AFSC) through June 30, 2019. The surveillance population included all active component (AC) Air Force members serving at any time from Oct. 1, 2003 through Dec. 31, 2018. Diagnoses were ascertained from administrative medical records maintained in the Defense Medical Surveillance System (DMSS) that document outpatient and inpatient encounters of active component service members. Such records reflect care in fixed military treatment facilities of the Military Health System (MHS) and in civilian health care settings where care is paid for by the MHS. Health care encounters of deployed service members were obtained from the Theater Medical Data Store (TMDS).

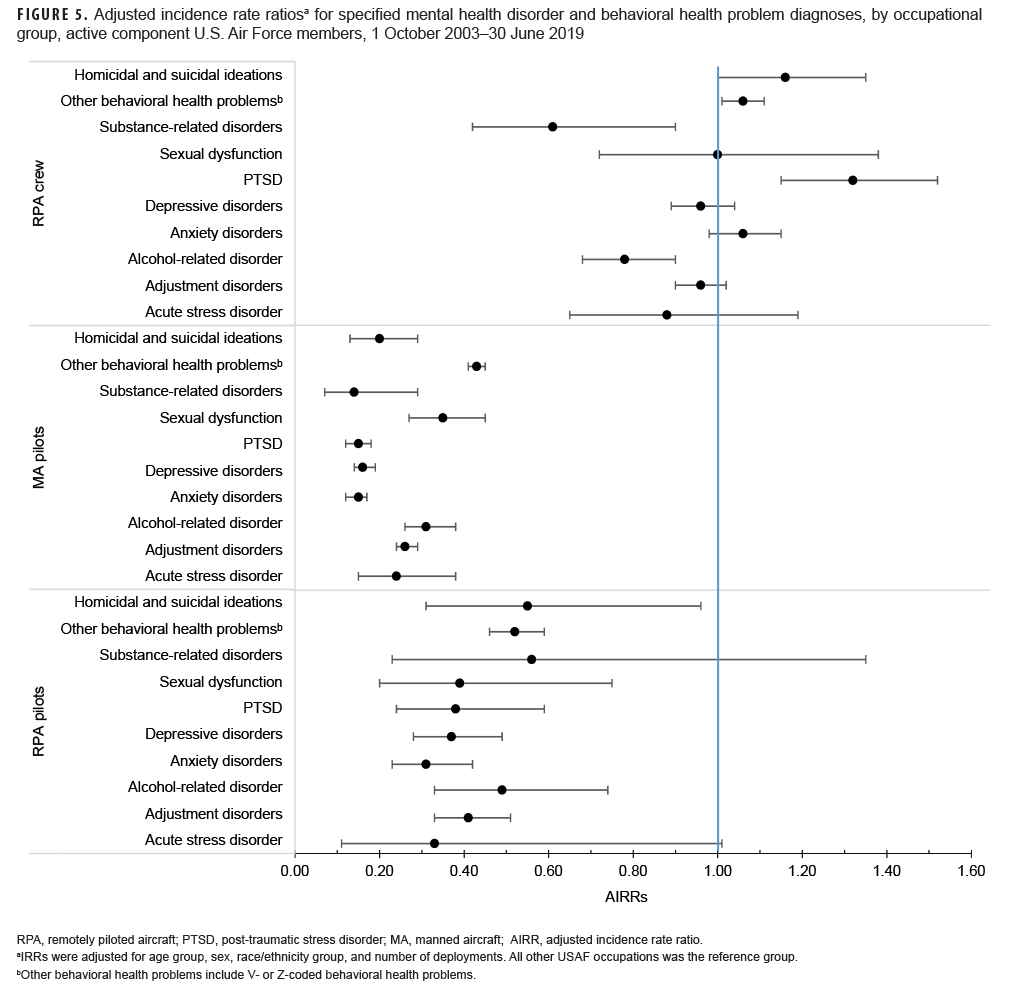

This analysis included service members in 1 of 4 occupational groups (categorized by AFSC): RPA pilots, MA pilots, RPA crew, and all other USAF occupations (Table 1). If service members served in multiple AFSCs during their military career, they were assigned to the highest AFSC they had held, as designated by a ranking of the 4 AFSC groups (highest to lowest): RPA pilot, MA pilot, RPA crew, all other USAF. For example, if a service member had served as an RPA crew member, other USAF occupation, and an RPA pilot during the course of his/her career, then that person was designated as an RPA pilot for the purposes of this study. Only MA pilots with a history of having deployed for at least 30 days to OEF, OIF, or OND were included in the analysis.

The follow-up period for RPA/MA pilots, RPA crew, or other USAF members began after completion of 30 days of service (person-time began at this point). They were censored from observation at separation from active duty or at the end of the surveillance period. Prevalent cases were excluded but an incident case in one outcome category did not preclude persons from being incident cases in another outcome category. For example, an incident case of PTSD would not preclude that same person from being counted as an incident case of depression.

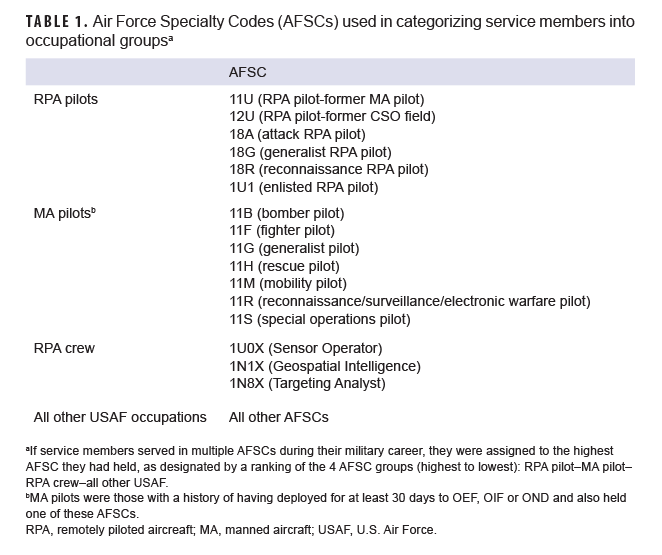

There were 4 main categories of outcomes: MH disorders (acute stress disorder, adjustment disorders, alcohol-related disorders, anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, PTSD, sexual dysfunction not due to substance/physiologic condition, and substance-related disorders), behavioral health problems (suicidal/homicidal ideation, family/support group problems, maltreatment-related, lifestyle problems, and substance abuse counseling), sleep disorders (excluding sleep apnea and other physiologic etiologies), and fatigue. To meet the case definition for a MH disorder, a person must have had either 1 hospitalization with a defining International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD-9)/International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) diagnosis code (Table 2) in the first or second diagnostic position or 2 or more outpatient or TMDS encounters occurring within 180 days (not on same day) or 1 outpatient encounter in a psychiatric or mental health care specialty setting defined by Medical Expense and Performance Reporting System (MEPRS) code starting with "BF", with a case-defining diagnosis in the first or second diagnostic position. To meet the case definitions for a BH problem, sleep disorder, or fatigue, 1 encounter (inpatient or outpatient/TMDS) with the defining diagnosis in any diagnostic position was required. The case definitions used in this analysis are generally consistent with the AFHSD surveillance case definitions for mental heath conditions; however, a notable difference is the exclusion of ICD-10 code F10.11 which represents alcohol use disorders in remission.

Incidence rates (IRs) per 1,000 person-years (p-yrs) and adjusted incidence rate ratios (AIRRs) with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using all other USAF occupations as the reference group. For the purposes of examining IRs over time, the IRs of MH disorders and BH problems were combined as 1 outcome and also broken down into specific categories. IRRs were calculated using a multivariable Poisson regression model that adjusted for age group, sex, race/ethnicity group, and number of deployments. Data analysis was carried out using SAS/STAT software, version 9.4 (2014, SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R, version 3.6.2 (2019, R Core Team).

Results

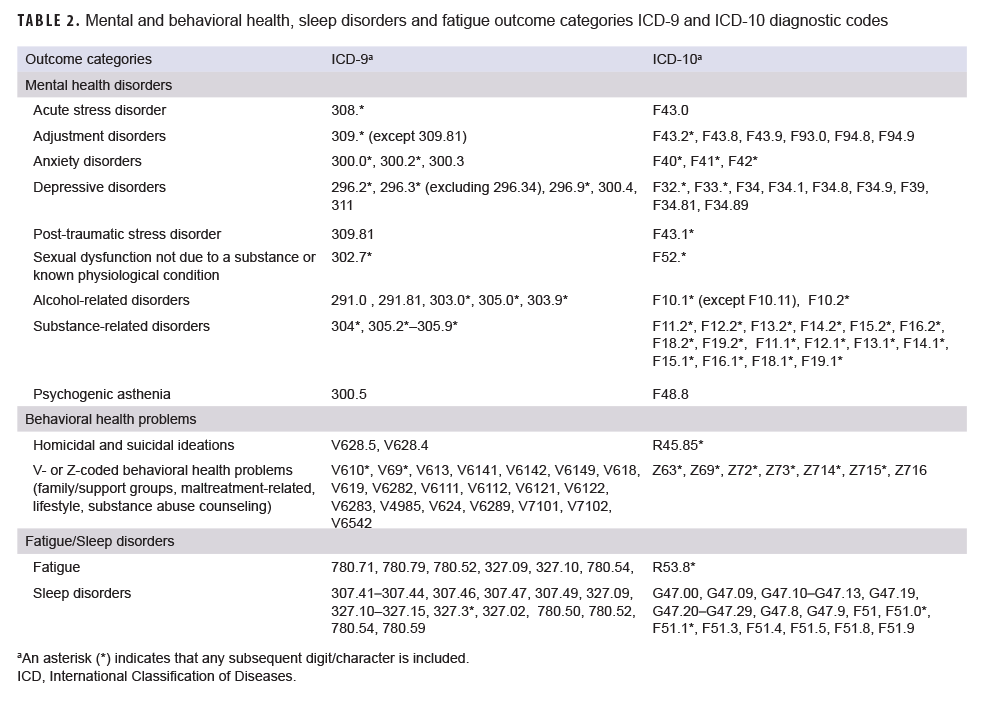

USAF members in service during the surveillance period included 2,687 RPA pilots, 13,384 MA pilots (with at least 1 deployment), 6,793 RPA crew, and 840,812 service members in other occupations (Table 3). Several differences in demographic and military characteristics were apparent between these occupational groups. Both RPA and MA pilots were predominately male (94.0% and 94.5%, respectively) while RPA crew and other USAF were less so (71.5% and 78.7%, respectively). RPA pilots tended to be older (46.7% aged 30 years or older) than other occupational groups: MA pilots (26.5%); RPA crew (12.6%); and other USAF (19.1%). RPA and MA pilots were predominantly non-Hispanic White (82.7% and 86.6%, respectively) and RPA crew and other USAF less so (69.8% and 66.8%, respectively). More than one-third (35.3%) of MA pilots had 3 or more deployments followed by RPA pilots (18.8%), other USAF (4.5%), and RPA crew (2.6%).

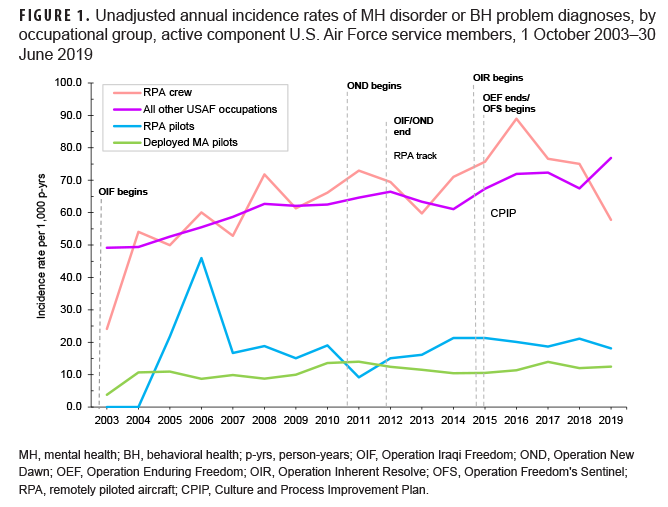

Over the course of the surveillance period, crude (unadjusted) annual rates of incident MH disorder and BH problem diagnoses were consistently higher among service members working as RPA crew and those in all other USAF occupations compared to RPA and MA pilots (Figure 1). Incidence rates of MH disorder and BH problem diagnoses among all other USAF occupations showed a pronounced and relatively steady increase over time from 49.2 per 1,000 p-yrs in 2003 to 76.9 per 1,000 p-yrs in 2019. Rates for RPA crew also increased over time, but with greater year-to-year fluctuations. Compared to all other USAF occupations and RPA crew, rates among MA pilots remained relatively low and the absolute increase in rates was relatively small over the period (3.8 per 1,000 p-yrs in 2003 to 12.5 per 1,000 p-yrs in 2019).

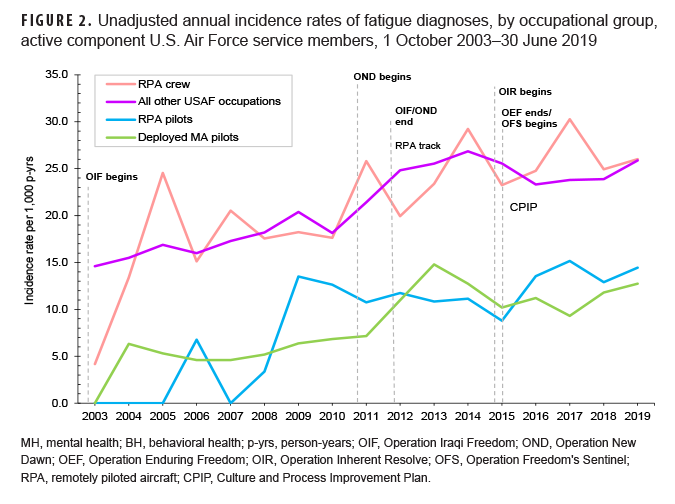

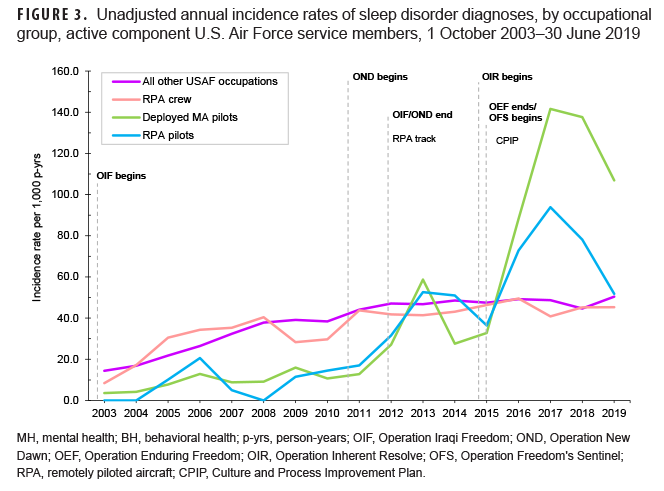

Patterns of rates of incident fatigue diagnoses over time were similar to those observed for MH disorder and BH problem diagnoses in that rates were consistently higher among RPA crew and those in all other USAF occupations compared to RPA and MA pilots (Figure 2). All occupational groups showed steady increases in fatigue incidence over the surveillance period. Crude annual rates of incident sleep disorder diagnoses showed a different pattern by occupational group in which RPA crew and other USAF occupations demonstrated slight increases over the course of the surveillance period (Figure 3). In contrast, there were marked increases in the rates of sleep disorder diagnoses in both pilot groups beginning in 2010. Rates in these groups peaked in 2013 and again more dramatically in 2017 followed by declines through 2019.

Multivariable regression analysis using all other USAF occupations as the reference group revealed that AIRRs for MH disorder or BH problem diagnoses were lowest among MA pilots (AIRR=0.31; 95% CI: 0.29–0.33) followed by RPA pilots (AIRR=0.44; 95% CI=0.38–0.50) (Figure 4). The adjusted incidence rate of this outcome category among RPA crew showed no difference compared to the rate for those in all other USAF occupations (AIRR=0.97; 95% CI: 0.93–1.02). Fatigue diagnoses followed a similar pattern with MA pilots (AIRR=0.52; 95% CI: 0.49–0.56) and RPA pilots having lower risk (AIRR=0.61; 95% CI: 0.52–0.72) compared to those in all other USAF occupations, and RPA crew showing mildly elevated risk (AIRR=1.10; 95% CI: 1.02–1.18). Sleep disorders demonstrated a different pattern in which all groups showed elevated risk compared to those in all other USAF occupations, with RPA pilots at highest risk: RPA pilots (AIRR=1.32; 95% CI: 1.21–1.43); MA pilots (1.20; 95% CI: 1.16–1.24); and RPA crew (1.10; 95% CI: 1.04–1.16).

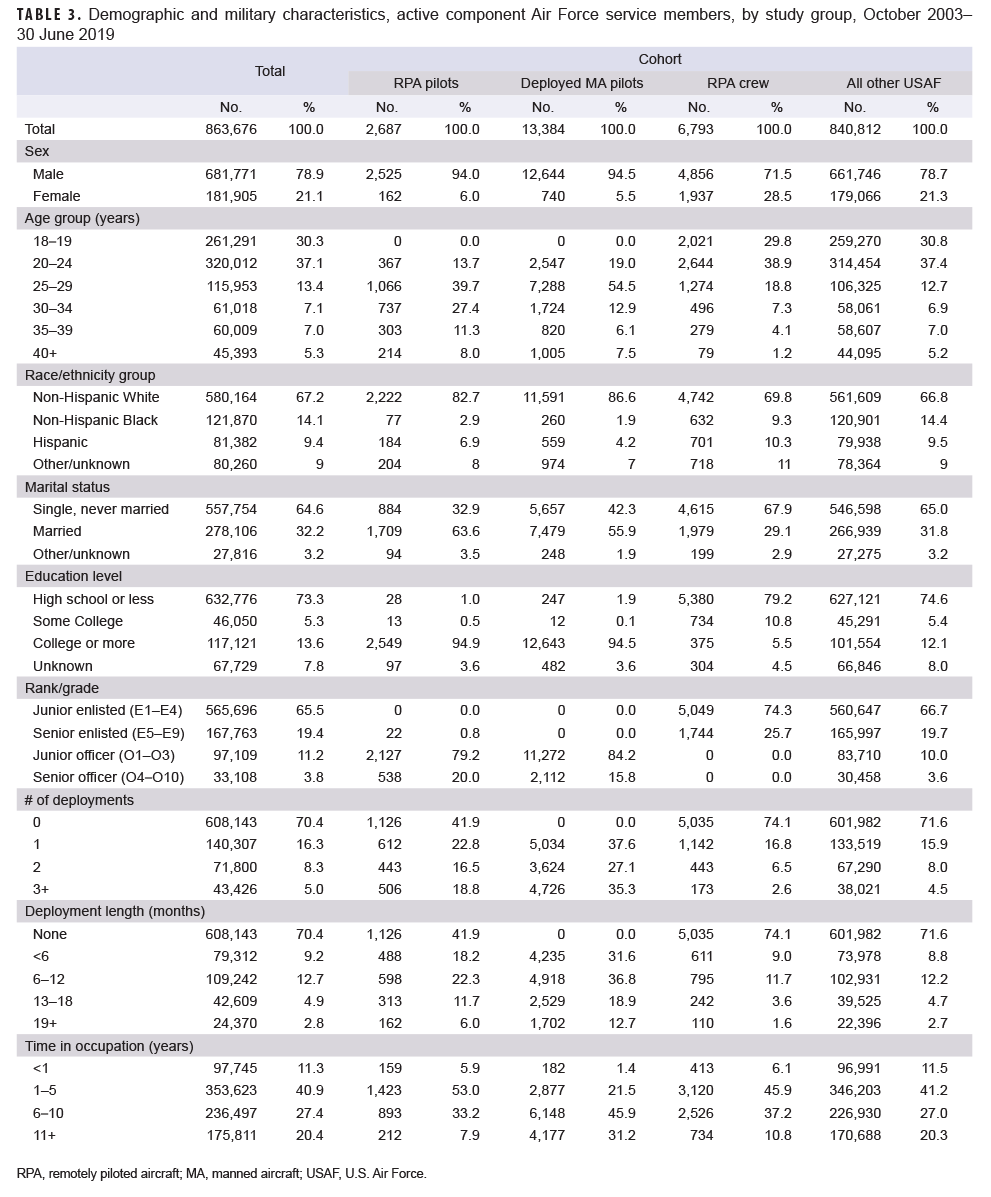

Analysis of AIRRs for specific MH disorder and BH problem diagnoses by occupational group yielded patterns broadly similar to those observed for the overall outcome categories (Figure 5). Compared to those in all other USAF occupations, RPA and MA pilots were at lower risk of all of the specific conditions examined. Patterns of specific MH and BH conditions among RPA crew were more varied, however, with RPA crew having significantly higher risk of PTSD (AIRR=1.32; 95% CI: 1.15–1.52), and other behavioral health problems (AIRR=1.06; 95% CI: 1.01–1.11) compared to those in all other USAF occupations, and significantly lower risk of alcohol- (AIRR=0.78; 95% CI=0.68–0.90) and substance-related disorders (AIRR=0.61; 95% CI=0.42–0.90).

Editorial Comment

This study found that MA pilots and RPA pilots had lower adjusted incidence rates of MH disorder and BH problem diagnoses compared to those of other USAF service members, and RPA crew did not have a statistically significantly different adjusted incidence of these outcomes compared to USAF service members in other occupations. MA and RPA pilots had lower adjusted incidence rates of fatigue diagnoses while RPA crew had higher incidence than other USAF members. Interestingly, with regard to sleep disorder diagnoses, pilots of both types and RPA crew had higher adjusted incidence rates compared to those in all other USAF occupations.

Findings of lower incidence rates of MH/BH conditions among pilots compared to all other USAF members were not entirely unexpected; a previous study also reported a lower risk of MH/BH outcomes among USAF pilots compared to USAF members overall.11 Several explanations for these lower rates are conceivable. Flying duty, unsurprisingly, is the defining feature of the pilot occupation and is centrally important to pilots and their careers. Diagnosis of a MH disorder results in revocation of a pilot's flying status until they are able to receive a waiver after successful treatment and resolution of the condition.

However, even if a waiver is granted, there is often a period ranging from 3 months to 1 year during which the pilot is not allowed to perform flying duties.12 This threat of losing flying status and the potential harm to career may make seeking help for MH conditions less common among pilots and may partially explain these results. Another factor, the so-called healthy flyer effect, may also contribute to the lower rates of incident mental health disorder diagnoses and behavioral health problems observed in pilots. Mental and physical requirements to become a pilot are more stringent than for other USAF occupations which may screen out potential pilot candidates at higher risk of these outcomes. Since the creation of the RPA pilot AFSC in 2003, 2 notable changes have occurred within the pilot career field. In 2010, the USAF created an independent AFSC for RPA pilots. Additionally, the first enlisted RPA pilots also came into the USAF for the 2017–2018 fiscal year. In the context of these recent changes, this study's results were consistent with the previous study of pilots in 2013.11

RPA crew had similar incidence rates of MH/BH outcomes compared with other USAF personnel. This finding persisted even after adjusting for age group, sex, race/ethnicity group, and number of deployments. The persistence of this finding is not entirely unexpected given similar demographic characteristics between RPA crew and the rest of the non-pilot USAF. However, for several specific MH/BH outcomes, RPA crew did demonstrate a significant difference in incidence rates compared to those in all other USAF occupations. RPA crew had lower adjusted incidence rates of substance- and alcohol-related disorder diagnoses but higher rates of PTSD and BH problems which is consistent with a study of RPA intelligence personnel between 2006 and 2010.13 It may be that interventions targeted for the RPA crew occupational field could help reduce their elevated incidence of these 2 conditions.

Notably, all groups had elevated risk for sleep disorders compared to those in other USAF occupations. One possible explanation for the elevated incidence of sleep disorders among pilots may be that they feel more at ease reporting to medical professionals for a sleep-related complaint than for a potential underlying MH disorders or BH problems. This elevated risk of sleep disorders among RPA pilots, MA pilots, and RPA crew may be an accurate reflection of increased sleep-related complaints in pilots and crew compared to those in other USAF occupations. This elevated risk may be partly attributable to deployment and/or shift work which can disrupt normal sleep cycles. Sleep complaints could also be a proxy for MH disorders or BH problems. RPA pilot, MA pilot, and RPA crew occupations have features which elevate risk of related concerns such as burnout and exhaustion. This finding is consistent with prior studies of RPA and MA pilots and RPA crews.7,8,14

The higher risk of sleep disorders in pilots highlights the potential for adverse long-term outcomes such as burnout, early attrition, and poorer operational performance.14 Work is already underway to improve USAF service member sleep and reduce fatigue by the Air Force Research Laboratory 711th Human Performance Wing, where researchers are studying sleep with a focus on aircrew.15

The current study may inform other efforts such as the Culture and Process Improvement Plan (CPIP) which was developed by USAF leadership in 2015 to improve morale among the RPA community. Heavy workloads combined with manning challenges spurred this effort along with the finding that the top concern among the RPA community was insufficient time outside of work duties.16 CPIP may have played a role in some of the trends observed in this study by encouraging service members to seek help for these conditions. Unadjusted incidence rates of fatigue in 2015 increased by over 60% among RPA pilots and rates of sleep disorders jumped by 100% in RPA pilots and by nearly 170% in MA pilots. Sleep disorder incidence rates continued to increase until 2018 when they began to fall back towards previous levels.

Several limitations are present in this study. First, the choice to only include MA pilots who have been deployed means that some MA pilots were excluded from the analysis and not considered for the outcomes of interest. The number of MA pilots who have never deployed is likely to be small, but there should be further investigation into the extent of never-deployed pilots and whether they differ in these outcomes. A second limitation of this analysis is related to the classification of exposure. Individuals were only allowed to contribute person-time (and outcomes) towards a single exposure group (RPA pilot, MA pilot, or RPA crew) regardless of whether they served in other groups. Choosing this method aims to most closely represent the final career path of the member to reflect that RPA pilot and MA pilot are more likely to be the most recent AFSC category. This approach was taken given the difficulty of assigning outcomes occurring at different times in a member serving in more than 1 AFSC category. This choice would tend to result in bias towards increased incidence of outcomes assigned to RPA pilots and slightly less so MA pilots. However, except in the sleep outcome, the opposite trend was seen with MA and RPA pilots demonstrating lower incidence than other groups. Therefore, these findings may be slight overestimates of actual incidence. Finally, the low annual case counts for some occupational groups, particularly during the first years of the surveillance period, likely contributed to the pronounced fluctuations in IR estimates observed.

In conclusion, this study provides a longitudinal perspective on an expanded set of operationally-relevant outcomes among RPA/MA pilots and RPA crew. Future operational health studies may explore whether under-reporting of MH/BH outcomes among pilots is a significant concern and may be able to examine methods of reducing sleep disorders among all air crew.

Author Affiliations: Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, MD (Capt Kieffer); Armed Forces Health Surveillance Division (Dr. Stahlman).

Acknowledgements: Dr. Clara Ziadeh and Ms. Zheng Hu (Armed Forces Health Surveillance Division) was instrumental in performing data abstraction and statistical analysis.

Disclaimer: The contents, views or opinions expressed in this publication or presentation are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect official policy or position of Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, the Department of Defense (DOD), or Departments of the Army, Navy, or Air Force. Mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

References

- Weatherington D. Current and Future Potential for Unmanned Aircraft Systems. 2010.

- Cancian M. U.S. Military Forces in FY 2020: Air Force. Cent Strateg Int Stud. 2019. Accessed 31 March 2020. https://www.csis.org/analysis/us-military-forces-fy-2020-air-force

- Stahlman S, Oetting AA. Mental health disorders and mental health problems, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2007–2016. MSMR. 2018;25(3):2–11.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Absolute and relative morbidity burdens attributable to various illnesses and injuries, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2018. MSMR. 2019;26(5):2–10.

- Bryan C, Goodman T, Chappelle W, Thompson W, Prince L. Occupational Stressors, Burnout, and Predictors of Suicide Ideation Among U.S. Air Force Remote Warriors. Mil Behav Heal. 2018;6(1):3–12.

- Hardison, Chaitra M., Aharoni E, Larson C, Trochlil S, Hou AC. Stress and Dissatisfaction in the Air Force's Remotely Piloted Aircraft Community. Santa Monica, CA; 2017.

- Armour C, Ross J. The Health and Well-Being of Military Drone Operators and Intelligence Analysts: A Systematic Review. Mil Psychol. 2017;29(2):83–98.

- Chappelle W, Goodman T, Reardon L, Prince L. Combat and operational risk factors for post-traumatic stress disorder symptom criteria among U.S. Air Force remotely piloted aircraft "Drone" warfighters. J Anxiety Disord. 2019;62:86–93.

- Phillips A, Sherwood D, Greenberg N, Jones N. Occupational stress in Remotely Piloted Aircraft System operators. Occup Med (Lond). 2019;69(4):244–250.

- Neville KJ, Bisson RU, French J, Boll PA, Storm WF. Subjective Fatigue of C-141 Aircrews during Operation Desert Storm. Hum Factors J Hum Factors Ergon Soc. 1994;36(2):339–349.

- Otto JL, Webber BJ. Mental health diagnoses and counseling among pilots of remotely piloted aircraft in the U.S. Air Force. MSMR. 2013;20(3):3–8.

- Department of the Air Force. USAF Medical Service. Aerospace Medicine Waiver Guide. Air Force Waiver Guide. 2 Dec 2020. Accessed March 31, 2020. https://www.afrl.af.mil/Portals/90/Documents/711/USAFSAM/USAF-waiver-guide-201202.pdf?ver=CfL6CVKyrAbqyXS7A-OX_A%3D%3D

- Ostrowski, Kris Anthony, Psychological Health Outcomes Within USAF Remotely Piloted Aircraft Support Career Fields. Scholarly Commons. 2016; PhD Dissertations and Master's Theses. 203.

- Chappelle W, McDonald K, Prince L, Goodman T, Ray-Sannerud BN, Thompson W. Assessment of Occupational Burnout in U.S. Air Force Predator/Reaper "Drone" Operators. Mil Psychol. 2014;26(5–6):376–385.

- Bedi S. Air Force studies fatigue, sleep to enhance readiness. Air Force Surgeon General Public Affairs. Accessed March 31, 2020. https://www.af.mil/News/Article-Display/Article/2047256/air-force-studies-fatigue-sleep-to-enhance-readiness/

- Everstine BW. Don't Fear the Reaper. Air Force Mag. 2016. Accessed 31 March 2020. https://www.airforcemag.com/article/dont-fear-the-reaper/