Background

The post-9/11 U.S. military conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan lasted over a decade and yielded the most combat casualties since the Vietnam War.1 While patient survivability increased to the highest level in history, a changing epidemiology of combat injuries emerged whereby focus shifted to addressing an array of long-term sequelae, including physical, psychological, and neurological issues.2,3 The long-term effects of combat injury can adversely impact well-being and exact a significant burden on the health care system.4–6

Physical pain is common among military personnel returning from deployment, particularly those injured in combat,7–9 and is associated with detrimental effects such as medical discharge10 and substance use disorders.11 Pain has also been linked to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which is common in veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts.12 The mutual maintenance model posits that PTSD symptoms may exacerbate chronic pain and, in turn, pain may contribute to or enhance existing PTSD symptoms.13 PTSD is associated with negative outcomes among veterans with chronic pain, including disability, decreased functioning, and sleep disturbances,14 making the study of pain and PTSD essential for improved patient care and rehabilitation.

Previous research on the co-occurrence of pain and PTSD in wounded service members has been limited by small sample sizes, specific injuries, or short follow-up periods.15–17 The present study adds to the existing literature by examining the association between pain and PTSD screening outcomes nearly a decade after combat injury among a large, national sample of service members and veterans who were injured during deployment and experienced a wide range of injuries.

Methods

Data were collected from the Wounded Warrior Recovery Project (WWRP).4 Participants are identified from the Expeditionary Medical Encounter Database (EMED), a deployment health repository maintained by the Naval Health Research Center that includes clinical records of service members injured in overseas contingency operations since 2001.18 Individuals whose data are in the EMED are approached via postal mail and email to provide informed consent for participation in the WWRP and to complete biannual assessments of patient-reported outcomes for 15 years. Enrollment is conducted on a rolling basis, and data collection is ongoing.

The present study utilized cross-sectional data from the seventh wave of the WWRP (i.e., 36 months post-baseline survey), when participants were asked to report on their pain during the past 6 months using the Chronic Pain Grading Scale.19 The measure was introduced into the WWRP in 2015 and was asked of all participants only at the seventh wave. Standardized scoring procedures were used to calculate (1) pain intensity (a composite variable derived from current pain, worst pain in the past 6 months, and average pain in the past 6 months), (2) frequency of pain interference (number of days in the past 6 months that the respondent has been kept from their usual activities such as work, school, or housework because of pain), and (3) level of pain interference (a composite variable of how much pain has interfered with daily activities; recreational, social, and family activities; and ability to work, including housework).

PTSD screening status was measured using the PTSD Checklist–Civilian version (PCL-C) and PTSD Checklist for the DSM-5 (PCL-5). Both versions of the PCL are comparable in military personnel and veterans.20 WWRP measures and procedures were updated in late 2018 to remain consistent with current standards of measurement of PTSD symptoms. Scores were summed for each PCL-related measure. Standard cutoffs of 44 and 33 indicated positive screens for PTSD using the PCL-C and PCL-5, respectively.21,22

Data from 2,649 combat-injured service members and veterans who participated in the WWRP between 1 December 2015 and 30 September 2021 were included in the analysis. Injury date, Injury Severity Scores (ISS), and demographics were obtained from the EMED. The ISS is a scoring system that accounts for multiple injuries in a patient and provides an overall measure of injury severity that ranges from 0 (no injury) to 75 (fatal injury). ISS was categorized as mild (1–3), moderate (4–8), and serious/severe (ISS 9+). Independent sample t-tests were used to examine mean differences in pain variables by PTSD screening status. An alpha level of .05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics, version 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

Results

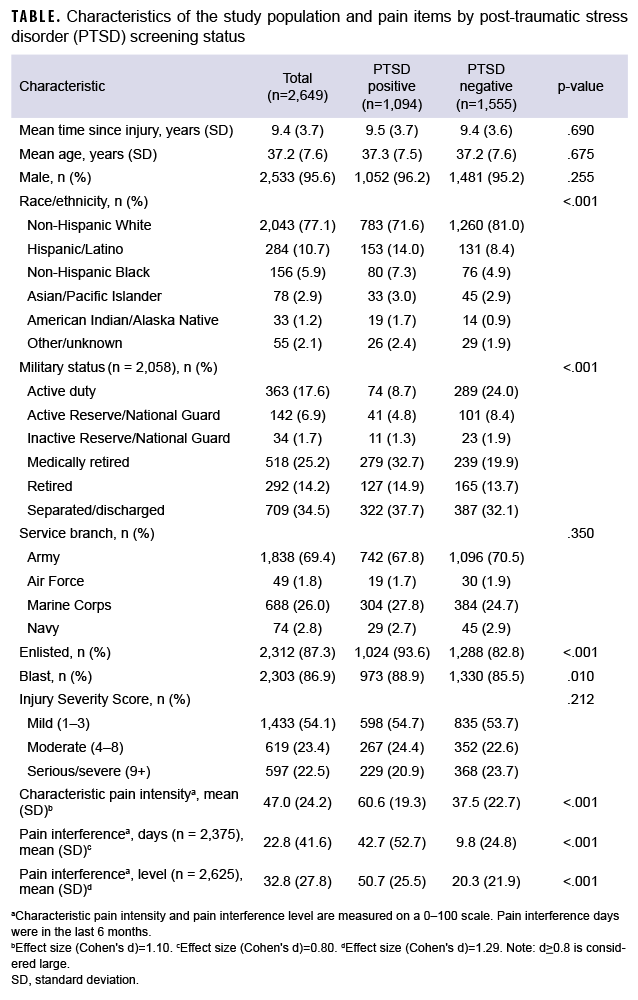

Participants were mostly enlisted, non-Hispanic White males in the Army (Table). At the time of the WWRP assessment, mean age was 37.2 years (standard deviation [SD]=7.6) and average time since injury was 9.4 years (SD=3.7). A majority of participants (86.9%) were injured in a blast and over one-half (54.1%) sustained mild injuries overall. Injury severity was not associated with PTSD screening status (p=.212). Participants who screened positive for PTSD had higher average pain intensity (60.6 vs. 37.5, p<.001, d=1.10), days of pain interference (42.7 vs. 9.8, p<.001, d=0.80), and level of pain interference (50.7 vs. 20.3, p<.001, d=1.29) than those who screened negative.

Editorial Comment

This study describes a significant association between PTSD screening outcomes and pain following combat injury. These results are consistent with previous literature and reaffirm that psychological and physical health issues can overlap and potentially complicate patient management.3 In a report by Shipherd et al.,23 66% of veterans who sought treatment for PTSD had comorbid chronic pain. Another study found that diagnosis of PTSD yielded 5 times greater odds of persistent pain complaints,24 and other research suggests a link between greater pain severity after combat injury and PTSD risk.25 Further, the polytrauma clinical triad (co-occurrence of concussion, pain, and PTSD) was found in 42% of military polytrauma patients.8 Sharp and Harvey13 highlighted several possible pathways whereby pain and PTSD could be mutually maintaining, including pain acting as a reminder of the trauma, reduced activity levels, and increased pain perception due to elevated anxiety. Notably, injury severity in the present study was not associated with PTSD screening status. This finding is consistent with previous research17 and can be explained by ISS being a measure of mortality risk, which may not be directly related to other outcomes, such as mental health. Future studies are needed to elucidate the etiological pathways of comorbid pain and PTSD after combat injury. Because pain and PTSD can co-occur many years after injury, the early recognition and identification of these conditions in primary care settings and through periodical health assessments may be important to refine clinical practice and, ultimately, improve the overall public health of the military.

Furthermore, the use of multidisciplinary health care teams should be examined and considered for use in future military conflicts to address co-occurring physical and psychological issues, which negatively impact long-term quality of life.3 A similar model was successfully employed to increase return-to-duty rates following concussion and could be adapted to address other injuries.26 Such interventions should be considered for veterans in long-term care and also during the early phase following combat injury, as recent research demonstrated that symptom complaints in the initial year post-injury predicted mental and physical health years later.27

This analysis has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. A key limitation is due to the cross-sectional design of this study; because PTSD and pain were measured at a single point in time, their temporality could not be assessed. Elucidating this relationship could be useful in developing targeted intervention and treatment strategies. Further, measures were obtained on average 9 years after injury, and other factors unaccounted for in the present study (e.g., depression, sleep problems, concussion) may influence the relationship between pain and PTSD. Additional research is needed to examine this relationship over time and include an assessment of confounders. Nevertheless, the findings suggest that pain is associated with PTSD years after injury and could inform medical providers involved in the treatment and rehabilitation of military personnel after combat injury.

Author Affiliations

Naval Health Research Center, San Diego, CA (Dr. MacGregor, Dr. Jurick, Dr. McCabe, Dr. Harbertson, Ms. Dougherty, and Mr. Galarneau); Leidos, Inc., San Diego, CA (Dr. Jurick, Dr. McCabe, Dr. Harbertson, Ms. Dougherty); Axiom Resource Management, Inc., San Diego, CA (Dr. MacGregor).

Disclaimer

The authors are military service members or employees of the U.S. Government. This work was prepared as part of their official duties. Title 17, U.S.C. §105 provides that copyright protection under this title is not available for any work of the U.S. Government. Title 17, U.S.C. §101 defines a U.S. Government work as work prepared by a military service member or employee of the U.S. Government as part of that person’s official duties. Report No. 22-19 was supported by the U.S. Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery under work unit no. 60808. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, nor the U.S. Government. The study protocol was approved by the Naval Health Research Center Institutional Review Board in compliance with all applicable Federal regulations governing the protection of human subjects. Research data were derived from an approved Naval Health Research Center Institutional Review Board protocol, number NHRC.2009.0014.

References

- Goldberg MS. Casualty rates of US military personnel during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Defence Peace Econ. 2018;29(1):44–61.

- Cannon JW, Holena DN, Geng Z, et al. Comprehensive analysis of combat casualty outcomes in U.S. service members from the beginning of World War II to the end of Operation Enduring Freedom. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2020;89(suppl 2):S8–S15.

- MacGregor AJ, Zouris JM, Watrous JR, et al. Multimorbidity and quality of life after blast-related injury among US military personnel: a cluster analysis of retrospective data. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):578.

- Watrous JR, Dougherty AL, McCabe CT, Sack DI, Galarneau MR. The Wounded Warrior Recovery Project: a longitudinal examination of patient-reported outcomes among deployment-injured military personnel. Mil Med. 2019;184(3-4):84–89.

- Dalton MK, Jarman MP, Manful A, Koehlmoos TP, Cooper Z, Weissman JS, Schoenfeld AJ. The hidden costs of war: healthcare utilization among individuals sustaining combat-related trauma (2007–2018). Ann Surg. Published online ahead of print (2 March 2021).

- Geiling J, Rosen JM, Edwards RD. Medical costs of war in 2035: long-term care challenges for veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan. Mil Med. 2012;177(11):1235–1244.

- Wilkie R. Fighting pain and addiction for veterans. October 26, 2018. https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/articles/fighting-pain-addiction-veter

ans/. Accessed March 4, 2022.

- Lew HL, Otis JD, Tun C, Kerns RD, Clark ME, Cifu DX. Prevalence of chronic pain, posttraumatic stress disorder, and persistent postconcussive symptoms in OIF/OEF veterans: polytrauma clinical triad. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2009;46(6):697-702.

- Mazzone B, Farrokhi S, Hendershot BD, McCabe CT, Watrous JR. Prevalence of low back pain and relationship to mental health symptoms and quality of life after a deployment-related lower limb amputation. Spine. 2020;45(19):1368–1375.

- Benedict TM, Singleton MD, Nitz AJ, Shing TL, Kardouni JR. Effect of chronic low back pain and post-traumatic stress disorder on the risk for separation from the US Army. Mil Med. 2019;184(9-10):431–439.

- Dembek ZF, Chekol T, Wu A. The opioid epidemic: challenge to military medicine and national security. Mil Med. 2020;185(5-6):e662–e667.

- Peterson AL. General perspective on the U.S. military conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan after 20 years. Mil Med. 2021.

- Sharp TJ, Harvey AG. Chronic pain and posttraumatic stress disorder: mutual maintenance? Clin Psychol Rev. 2001;21(6):857–877.

- Benedict TM, Keenan PG, Nitz AJ, Moeller-Bertram T. Post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms contribute to worse pain and health outcomes in veterans with PTSD compared to those without: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Mil Med. 2020;185(9-10):e1481–e1491.

- Giordano NA, Richmond TS, Farrar JT, Buckenmaier III CC, Gallagher RM, Polomano RC. Differential pain presentations observed across post-traumatic stress disorder symptom trajectories after combat injury. Pain Med. 2021;22(11):2638–2647.

- Castillo R, Carlini AR, Doukas WC, et al. Extremity trauma among United State military serving in Iraq and Afghanistan: Results from the Military Extremity Trauma and Amputation/Limb Salvage Study. J Ortho Trauma. 2021;35(3)e96–e102.

- Soumoff AA, Clark NG, Spinks EA, et al. Somatic symptom severity, not injury severity predicts probable posttraumatic stress disorder and major depressive disorder in wounded service members. J Trauma Stress. 2021;35(1):210–221.

- Galarneau MR, Hancock WC, Konoske P, et al. The Navy-Marine Corps Combat Trauma Registry. Mil Med. 2006;171(8):691–697.

- Von Korff M, Ormel J, Keefe FJ, Dworkin SF. Grading the severity of chronic pain. Pain. 1992;50(2):133–149.

- LeardMann CA, McMaster HS, Warner S, et al. Comparison of posttraumatic stress disorder checklist instruments from Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition vs fifth edition in a large cohort of US military service members and veterans. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(4):e218072.

- Hoge CW, McGurk D, Thomas JL, Cox AL, Engel CC, Castro CA. Mild traumatic brain injury in U.S. soldiers returning from Iraq. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(5):453–463.

- Blevins CA, Weathers FW, Davis MT, Witte TK, Domino JL. The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): development and initial psychometric evaluation. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28(6):489–498.

- Shipherd JC, Keyes M, Jovanovic T, et al. Veterans seeking treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder: what about comorbid chronic pain? J Rehabil Res Dev. 2007;44(2):153–166.

- Higgins DM, Kerns RD, Brandt CA, et al. Persistent pain and comorbidity among Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom/Operation New Dawn veterans. Pain Med. 2014;15(5):782–790.

- Giordano NA, Bader C, Richmond TS, Polomano RC. Complexity of the relationships of pain, posttraumatic stress, and depression in combat-injured populations: an integrative review to inform evidence-based practice. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2018;15(2):113–126.

- Spooner SP, Tyner SD, Sowers C, Tsao J, Stuessi K. Utility of a sports medicine model in military combat concussion and musculoskeletal restoration care. Mil Med. 2014;179(11):1319–1324.

- MacGregor AJ, Dougherty AL, D’Souza EW, et al. Symptom profiles following combat injury and long-term quality of life: a latent class analysis. Qual Life Res. 2021;30(9):2531–2540.