Abstract

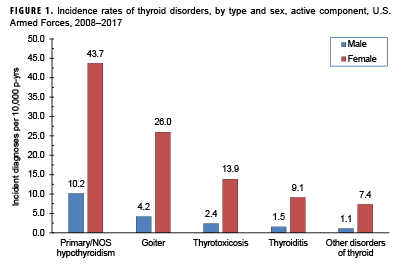

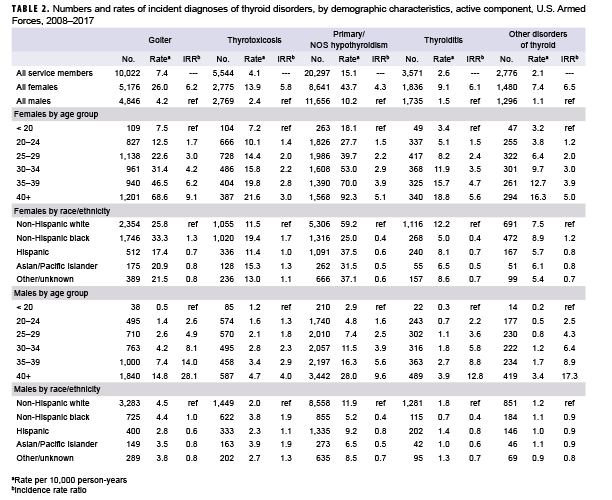

This analysis describes the incidence and prevalence of five thyroid disorders (goiter, thyrotoxicosis, primary/not otherwise specified [NOS] hypothyroidism, thyroiditis, and other disorders of the thyroid) among active component service members between 2008 and 2017. During the 10-year surveillance period, the most common incident thyroid disorder among male and female service members was primary/NOS hypothyroidism and the least common were thyroiditis and other disorders of thyroid. Primary/NOS hypothyroidism was diagnosed among 8,641 females (incidence rate: 43.7 per 10,000 person-years [p-yrs]) and 11,656 males (incidence rate: 10.2 per 10,000 p-yrs). Overall incidence rates of all thyroid disorders were 3 to 5 times higher among females compared to males. Among both males and females, incidence of primary/NOS hypothyroidism was higher among non-Hispanic white service members compared with service members in other race/ethnicity groups. The incidence of most thyroid disorders remained stable or decreased during the surveillance period. Overall, the prevalence of most thyroid disorders increased during the first part of the surveillance period and then either decreased or leveled off.

What Are the New Findings?

More than 40,000 cases of thyroid disorders were diagnosed during the 10-year surveillance period among active component service members. In contrast to previous findings, the current report indicates that the incidence of the five different thyroid disorders remained stable or decreased between 2008 and 2017.

What Is the Impact on Readiness and Force Health Protection?

Although thyroid disorders are treatable, hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism can result in periods of non-deployability, temporary duty profile, or need for medical waiver at the time of diagnosis or if there is a disruption in treatment. More severe cases of hyperthyroidism can take up to 1 year to stabilize, resulting in significant periods of limited deployability.

Background

The thyroid is an endocrine gland in the neck that secretes hormones which control the body metabolism. Disorders of the thyroid can be broadly classified into two groups: hyperthyroidism, in which the thyroid produces too much hormone, or hypothyroidism, in which the thyroid does not produce enough hormone.

The prevalence of hyperthyroidism in the U.S. is estimated to be 1.3% according to data from the NHANES-III, with the lowest prevalence observed among Mexican Americans and the highest among non-Hispanic whites.1 Hyperthyroidism can lead to thyrotoxicosis, a term that refers to having an excess of thyroid hormone in the body from any cause.2 In the U.S., thyrotoxicosis is more common among women, those with other thyroid conditions, and people over 60 years old.3,4 It is most commonly caused by Graves' disease, an autoimmune disorder affecting the thyroid. However, thyrotoxicosis can also be caused by thyroiditis (inflammation of the thyroid gland causing excess thyroid hormone to leak into the blood stream), thyroid nodules, overconsumption of iodine, or taking too much synthetic thyroid hormone.3 Symptoms of thyrotoxicosis include restlessness, rapid or irregular heartbeat, muscle weakness, anxiety, fatigue, trouble sleeping, heat intolerance, weight loss, and, in some cases, exophthalmos ("bulging eyes") and enlarged thyroid gland ("goiter"). Goiters are enlarged thyroid glands most commonly due to iodine deficiency. In the U.S., goiters are frequently caused by, and are also a symptom of, hyperthyroidism.5,6 If left untreated, large goiters can cause difficulty breathing and swallowing.

In the U.S., the prevalence of hypothyroidism is estimated to be 4.6%, with the lowest prevalence observed among non-Hispanic blacks compared to other race/ethnicity groups.1 Hypothyroidism is most commonly caused by Hashimoto's disease, an autoimmune disorder affecting the thyroid, which is much more common in women than men.7 Hashimoto's thyroiditis, also known as chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis, can cause hypothyroidism by impairing the ability of the thyroid to produce thyroid hormones. Hypothyroidism can also be caused by surgical removal of the thyroid or damage from radiation treatment. Symptoms of hypothyroidism include fatigue, depression, weight gain, dry skin, constipation, and muscle and joint pain.8

Hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism can significantly degrade the military operational capabilities of affected service members due to the various symptoms of the disorders. As a result, thyroid disorders are disqualifying conditions for entrance into the U.S. military.9 However, a 2012 MSMR analysis identified more than 37,000 incident cases of thyroid disorders among active component service members between 2002 and 2011.10 That analysis also documented a marked increase in the incidence rates of thyroid disorder diagnoses among service members during the period, particularly among males; however, this finding may have been due to increased testing for thyroid function disorders during 2002–2011.10 The current report summarizes the incidence, prevalence, and trends of thyroid disorders other than thyroid cancer among active component service members of the U.S. Armed Forces between 2008 and 2017.

Methods

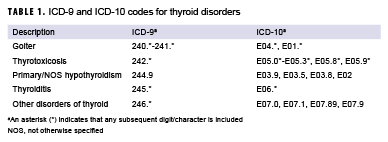

The surveillance period was Jan. 1, 2008 through Dec. 31, 2017. The surveillance population included all individuals who served in the active component of the Army, Navy, Air Force, or Marine Corps at any time during the surveillance period. Thyroid disorders were identified by diagnostic codes for "disorders of thyroid gland" recorded in standardized records of inpatient and outpatient encounters in military and non-military medical facilities documented in the Defense Medical Surveillance System (DMSS) (Table 1). Medical encounters from the Theater Medical Data Store (TMDS) were also included and were treated as outpatient encounters for the purpose of identifying incident cases. The diagnostic codes were grouped into five types of thyroid disorders based on the ICD coding system: goiter, thyrotoxicosis, primary/not otherwise specified (NOS) hypothyroidism, thyroiditis, and other disorders of thyroid. An incident case was defined by a hospitalization with a case-defining diagnostic code in any diagnostic position or two or more outpatient or in-theater diagnoses of the same thyroid disorder type between 1 and 180 days apart, with at least one of these diagnoses in a primary diagnostic position. One incident case diagnosis per individual per thyroid disorder type was counted. As such, a service member could count as a case for multiple different thyroid disorder types during the surveillance period.

Annual lifetime prevalence of each of the thyroid disorders was also ascertained. Prevalent cases were calculated as the number of service members who had ever been diagnosed with a particular thyroid disorder and who were in service during a given calendar year. Annual lifetime prevalence was calculated as the number of prevalent cases divided by the number of service members in service during a given year. Prevalence was expressed as the number of prevalent cases per 10,000 active component service members.

Individuals who met the case definition for a specific thyroid disorder prior to the surveillance period (i.e., prevalent cases) were excluded from the incidence rate calculation of that specific thyroid disorder. Among incident cases of thyroid disorders, the numbers of individuals with prior diagnoses of thyroid cancer (ICD-9: 193, 237.4; ICD-10: C73, D44.0) and of each of the four other thyroid disorder types were ascertained.

Results

Between 2008 and 2017, the most common incident thyroid disorder among male and female service members was primary/NOS hypothyroidism and the least common were thyroiditis and other disorders of thyroid (Table 2, Figure 1). During this period, primary/NOS hypothyroidism was diagnosed among 8,641 females (incidence rate: 43.7 per 10,000 person years [p-yrs]) and 11,656 males (incidence rate:10.2 per 10,000 p-yrs) (Table 2). Crude overall incidence rates of goiter and thyrotoxicosis were lower than for primary/NOS hypothyroidism but higher than for thyroiditis and other thyroid disorders.

Of the service members diagnosed with other disorders of thyroid, 26.0% of females and 19.8% of males had been previously diagnosed with goiter and 17.2% and 14.4% had been previously diagnosed with primary/NOS hypothyroidism, among females and males respectively (data not shown). In addition, 6.6% of female and 8.1% of male service members who were diagnosed with other disorders of thyroid had been previously diagnosed with thyroid cancer.

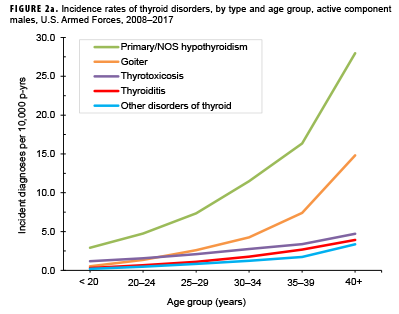

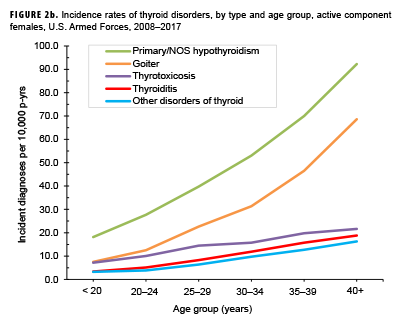

Overall incidence rates of thyroid disorders among females ranged from 4.3 (primary hypothyroidism) to 6.5 (other disorders of thyroid) times the rates of the respective conditions among males (Table 2). For both sexes, rates of thyrotoxicosis, thyroiditis, and other disorders of the thyroid increased approximately linearly with increasing age, with the greatest difference in incidence between those aged 35-39 years and those aged 40 or more. In contrast, overall rates of goiter and primary/ NOS hypothyroidism increased exponentially with increasing age (Figures 2a, 2b). For all thyroid disorder types, the median ages at incident case diagnoses were 3 to 5 years higher among males than females (data not shown).

Among both males and females, overall incidence rates of primary/NOS hypothyroidism and thyroiditis were higher among non-Hispanic white service members compared with service members in other race/ethnicity groups (Table 2). Among females, rates of goiter, thyrotoxicosis, and other disorders of thyroid were highest among non-Hispanic black service members. Among males, rates of goiter were higher among non-Hispanic black and non-Hispanic white service members, and rates of thyrotoxicosis were highest among non-Hispanic blacks and Asian/ Pacific Islanders.

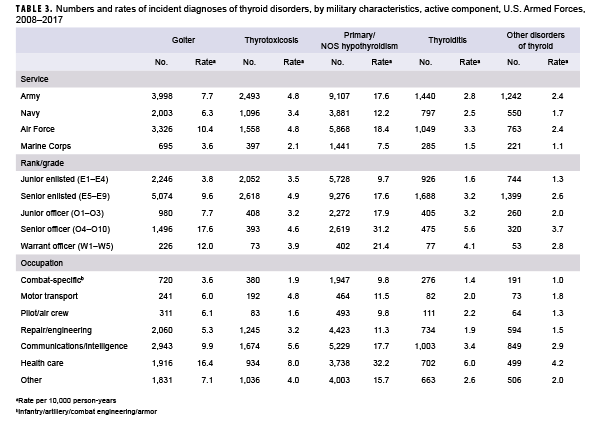

Across all thyroid disorder types, overall incidence rates were higher among service members in the Air Force compared with members of other service branches (Table 3). However, rates of thyrotoxicosis and other disorders of thyroid were similarly high among service members in the Army. Incidence rates of all thyroid disorder types, with the exception of thyrotoxicosis, were higher among senior officers and warrant officers, compared to those in other grades. Finally, service members in health care occupations had higher overall incidence rates of all thyroid disorder types compared with those in other occupations.

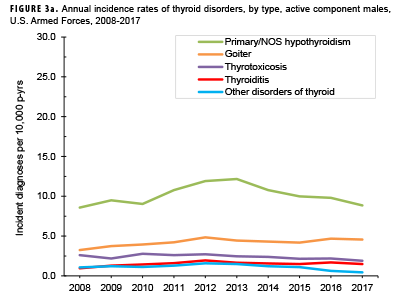

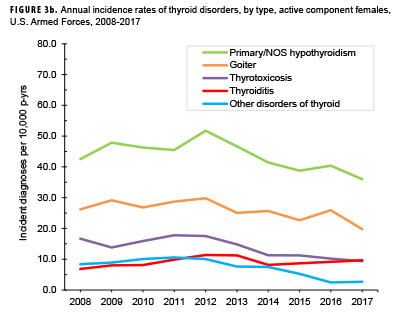

Among males, annual incidence rates for primary/NOS hypothyroidism showed the greatest variation compared to other thyroid disorders during the 10-year surveillance period, with a peak at 12.2 per 10,000 p-yrs in 2013 followed by a decrease to 8.9 per 10,000 p-yrs in 2017 (Figure 3a). Annual rates of the other thyroid disorder types among male service members were relatively low and stable during the surveillance period. Among females, with the exception of thyroiditis, crude annual incidence rates of each type of thyroid disorder decreased between 2008 and 2017 (Figure 3b). The most pronounced decrease in annual rates among female service members was observed for primary/NOS hypothyroidism (42.5 per 10,000 p-yrs in 2008 to 36.0 per 10,000 p-yrs in 2017).

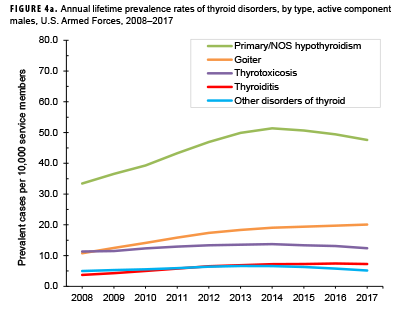

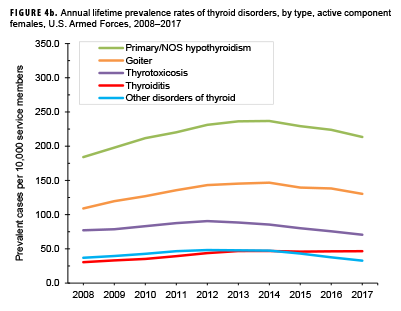

For both males and females, the prevalence of most thyroid disorders increased during the first part of the surveillance period and then either decreased slightly or leveled off (Figures 4a, 4b). Among female service members, the prevalence of primary/ NOS hypothyroidism, goiter, and thyroiditis peaked in 2014, and the prevalences of thyrotoxicosis and other disorders of thyroid peaked in 2012. Prevalences of thyrotoxicosis and primary/NOS hypothyroidism similarly peaked among males in 2014; however, the prevalence of thyroiditis peaked in 2016 and that of other disorders of thyroid peaked in 2013. Among male service members, the prevalence of goiter increased steadily throughout the 10-year surveillance period.

Editorial Comment

In contrast with a previous MSMR report documenting increases in thyroid disorder diagnoses among active component service members between 2002 and 2011, the results of the current analysis indicate that the incidence of thyroid disorders remained stable or decreased between 2008 and 2017. The 2012 MSMR report suggested that the increase in incidence during 2002–2011 may have been due, at least in part, to increased screening for thyroid disorders among service members affected by conditions with symptoms similar to those of thyroid disorders (e.g., depression, irritability, PTSD, musculoskeletal pain, sleep disorders), because incidence of these conditions increased sharply during the same period.10

Routine screening of young and healthy populations for thyroid disorders is not recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, or the American Thyroid Association.11,12 However, because many of the signs and symptoms associated with thyroid dysfunction overlap with the clinical manifestations of other conditions such as sleep, musculoskeletal, and mental health disorders, thyroid function testing is often done to rule out thyroid dysfunction as a cause or exacerbating factor for these conditions that are highly prevalent in the military. The current analysis did not assess rates of screening for thyroid disorders because there was no specific ICD-10 code for thyroid disorder screening (ICD-9 code V77.0 "screening for thyroid disorders maps to ICD-10 code Z13.29 encounter for screening for other suspected endocrine disorder"). As a result, the impact of screening for thyroid dysfunction during the 2008–2017 surveillance period is unknown.

However, a recent MSMR report documented that the incidence of mental health disorders among active component service members declined or remained stable between 2007 and 2016, which could suggest that there was decreased use of thyroid function testing to rule out thyroid dysfunction as a cause of or exacerbating factor for mental health disorders.13

McLeod and colleagues' study of U.S. military personnel during 1997–2011 demonstrated that the incidence of Graves disease, a frequent cause of thyrotoxicosis, was more common among non-Hispanic blacks and Asian/Pacific Islanders compared to non-Hispanic whites.14 This finding is consistent with the results of the current analysis, which indicate a higher incidence of thyrotoxicosis among non-Hispanic black and Asian/Pacific Islander service members. In contrast, McLeod et al.'s study also found that the incidence of Hashimoto thyroiditis, a common cause of hypothyroidism, was highest among non-Hispanic whites and lowest among non-Hispanic blacks.14 This is also consistent with the current study's finding that the incidence of thyroiditis was highest among non-Hispanic white service members and lowest among non-Hispanic black service members. Currently, it is unknown whether differences in rates of thyroid disorders by race/ethnicity are due to genetics, environmental exposures (e.g., smoking), or a combination of the two.

Similar to patterns observed in the U.S. civilian population,4 results of the current study showed that incidence and prevalence of all types of thyroid disorders were much more common among female compared to male service members. One potential risk factor among women is hormone imbalance caused by Click to closeestrogenAny of a group of steroid hormones which promote the development and maintenance of female characteristics of the body. Such hormones are also produced artificially for use in oral contraceptives or to treat menopausal and menstrual disorders.estrogen dominance.15 Estrogen receptors are widely expressed in most cells of the immune system and high estrogen levels may lead to deregulation and aberrant activation of the immune system.16 In addition, pregnancy can put stress on the thyroid gland and autoimmune thyroid disease may be triggered due to the shift in hormone levels or immune function during and after pregnancy.16,17

The finding that higher incidence of all thyroid disorders was observed among health care personnel is likely related to increased medical awareness, easier access to care, and, perhaps, older age compared to their respective counterparts in other occupations. Higher rates observed among senior enlisted personnel and officers are likely highly correlated with and confounded by age. In addition, higher rates observed among Army and Air Force service members may be related to differences in the demographic distributions of the services.

A significant limitation to this report is that the incidence rates of thyroid disorders were based on diagnoses recorded on standardized medical records. Because of this, the findings reflect the rates of thyroid functional abnormalities that were clinically detected and exclude subclinical dysfunction since not all service members are tested for thyroid disorders. Service members may be more likely to be tested for thyroid disorders as a rule-out diagnosis if they are presenting with fatigue, mental health disorders, sleeping disorders, musculoskeletal problems, etc., since these conditions may be viewed as symptoms of possible underlying thyroid disorder. As such, the incidence of thyroid disorders among service members may depend in part on the incidence of these other conditions.

Another limitation of the current analysis is related to the implementation of MHS GENESIS, the new electronic health record for the Military Health System. During 2017, medical data from sites that were using MHS GENESIS were not available in DMSS. These sites include Naval Hospital Oak Harbor, Naval Hospital Bremerton, Air Force Medical Services Fairchild, and Madigan Army Medical Center. Therefore, medical encounters and person-time data for individuals seeking care at one of these facilities during 2017 were excluded from the analysis. Findings from this report nevertheless provide useful and updated information regarding the burden of thyroid disorders on the Military Health System.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank CDR Thanh D. Hoang (Walter Reed National Military Medical Center [WRNMMC], Bethesda, MD) for his feedback on the initial manuscript. The authors also thank COL Babette C. Glister (WRNMMC) for her valuable input regarding the impact of thyroid disorders on readiness and force health protection.

References

- Hollowell JG, Staehling NW, Flanders WD, et al. Serum TSH, T(4), and thyroid antibodies in the United States population (1988 to 1994): National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(2):489–499.

- Pearce, EN. Diagnosis and management of thyrotoxicosis. BMJ. 2006; 332(7554): 1369–1373.

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Hyperthyroidism (Overactive Thyroid). https://www.niddk.nih.gov/ health-information/endocrine-diseases/hyperthyroidism. Accessed on 29 Sept. 2018.

- Golden SH, Robinson KA, Saldanha I, Anton B, Ladenson PW. Clinical review: prevalence and incidence of endocrine and metabolic disorders in the United States: a comprehensive review. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(6):1853–1878.

- Bahn RS, Burch HB, Cooper DS, et al. American Thyroid Association; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. Hyperthyroidism and other causes of thyrotoxicosis: management guidelines of the American Thyroid Association and American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. Endocr Pract. 2011;17(3):456–520. Erratum in: Endocr Pract. 2013;19(2):384.

- Surks MI, Ortiz E, Daniels GH, et al. Subclinical thyroid disease: scientific review and guidelines for diagnosis and management. JAMA. 2004;291(2):228–238.

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Hashimoto's Disease. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/endocrine-diseases/hashimotos-disease. Accessed on 29 Sept. 2018.

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Hypothyroidism (Underactive Thyroid). https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/endocrine-diseases/hypothyroidism. Accessed on 29 Sept. 2018.

- Department of Defense. Instruction 6130.03, Medical Standards for Appointment, Enlistment, or Induction into the Military Services. Change 1. 30 March 2018. http://www.esd. whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dodi/613003p.pdf. Accessed on 6 Oct. 2018.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center. Thyroid disorders among active component military members, U.S. Armed Forces, 2002-2011. MSMR. 2012;19(10):7–10.

- LeFevre ML; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for thyroid dysfunction: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(9):641–650.

- Garber JR, Cobin RH, Gharib H, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for hypothyroidism in adults: co-sponsored by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and the American Thyroid Association. Endocr Pract. 2012;18(6):988–1028.

- Stahlman S, Oetting AA. Mental health disorders and mental health problems, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2007–2016. MSMR. 2018;25(3):2–11.

- McLeod DS, Caturegli P, Cooper DS, Matos PG, Hutfless S. Variation in rates of autoimmune thyroid disease by race/ethnicity in US military personnel. JAMA. 2014 ;311(15):1563–1565.

- Santin AP, Furlanetto TW. Role of estrogen in thyroid function and growth regulation. J Thyroid Res. 2011;2011:1–7.

- Fairweather D, Frisancho-Kiss S, Rose NR. Sex differences in autoimmune disease from a pathological perspective. Am J Pathol. 2008;173(3):600–609.

- Poppe K, Velkeniers B, Glinoer D. Thyroid disease and female reproduction. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2007;66(3):309–321.