What are the New Findings?

Annual incidence rates of at least 1 mental health disorder decreased between 2016 and 2018, then increased in 2019 and decreased again in 2020. Patterns of incidence rates among demographic subgroups and the most commonly occurring types of mental health disorder diagnoses are similar to findings reported in previous MSMR reports.

What is the Impact on Readiness and Force Health Protection?

Although the incidence of mental health disorders remained relatively stable in the past 5 years, mental health disorders continue to affect a large number of service members and account for a significant burden of medical care. Ongoing efforts are needed to promote help-seeking behavior to improve the psychological and emotional well-being of service members.

Abstract

Mental health disorders have historically accounted for significant morbidity, health care utilization, disability, and attrition from military service. From 2016 through 2020, a total of 456,293 active component service members were diagnosed with at least 1 mental health disorder and 84,815 were diagnosed with mental health problems related to family/support group problems, maltreatment, lifestyle problems, substance abuse counseling, or social environment problems. Crude annual incidence rates of at least 1 mental health disorder decreased between 2016 and 2018, then increased in 2019 and decreased again in 2020. Most of the incident mental health disorder diagnoses were attributable to adjustment disorders, anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, "other" mental health disorders, alcohol-related disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Similar to the last MSMR update, rates of incident mental health disorders were generally higher among female service members and Army members and declined with increasing age. Ongoing efforts to assist and treat service members should continue to promote help-seeking behavior to improve the psychological and emotional well-being of service members and reduce the burden of mental health disorders.

Background

In 2020, mental health disorders accounted for the largest total number of hospital bed days and the second highest total number of medical encounters for members of the active component of the U.S. Armed Forces.1 Prior MSMR reports have documented the increasing incidence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, adjustment disorders, and other mental health disorders from 2003 through 2011, followed by decreasing incidence through 2016 most notably for alcohol- and substance-related disorders, personality disorders, and depressive disorders.2,3 Between 2007 and 2016, the highest incidence rates of mental health disorders diagnosed among active component service members were for adjustment disorders, depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, "other" mental health disorders, and alcohol-related disorders, respectively.3 In general, crude incidence rates of mental health disorders have been observed to be highest among service members in the Army, females, and in younger age groups.2,3

Psychosocial and behavioral health problems related to difficult life circumstances (e.g., marital, family, other interpersonal relationships) are also important to consider for comprehensive surveillance of service members' mental health; these are often documented using International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD-9) V-codes and Z-codes in ICD-10. For example, 1 study found that service members who received mental health care (documented with V-coded diagnoses) were at greater risk of attrition from military service than those treated for only physical health conditions but at less risk of attrition than those who received mental health disorder-specific diagnoses.4 In addition, many studies have focused on the impact of mental health disorders such as PTSD among military-serving parents and their associations with increased problems in the family environment.5 However, family problems can also have independent associations with adverse outcomes such as suicide or medical evacuation from overseas deployments.6,7

This report summarizes the numbers, natures, and rates of incident mental health disorder diagnoses among active component U.S. service members over a 5-year surveillance period. It also summarizes the numbers, natures, and rates of incident "mental health problems" (documented with mental health-related V- or Z-codes in ICD-9 or ICD-10, respectively) among active component service members during the same period.

Methods

The surveillance period was 1 January 2016 through 31 December 2020. The surveillance population included all individuals who served in the active component of the Army, Navy, Air Force, or Marine Corps at any time during the surveillance period. All data used to determine incident mental health disorder-specific diagnoses and mental health problems were derived from records routinely maintained in the Defense Medical Surveillance System (DMSS). These records document both ambulatory encounters and hospitalizations of active component members of the U.S. Armed Forces in fixed military and civilian (if reimbursed through the Military Health System[MHS]) treatment facilities. Diagnoses were also derived from records of medical encounters of deployed service members that were documented in the Theater Medical Data Store (TMDS) in DMSS.

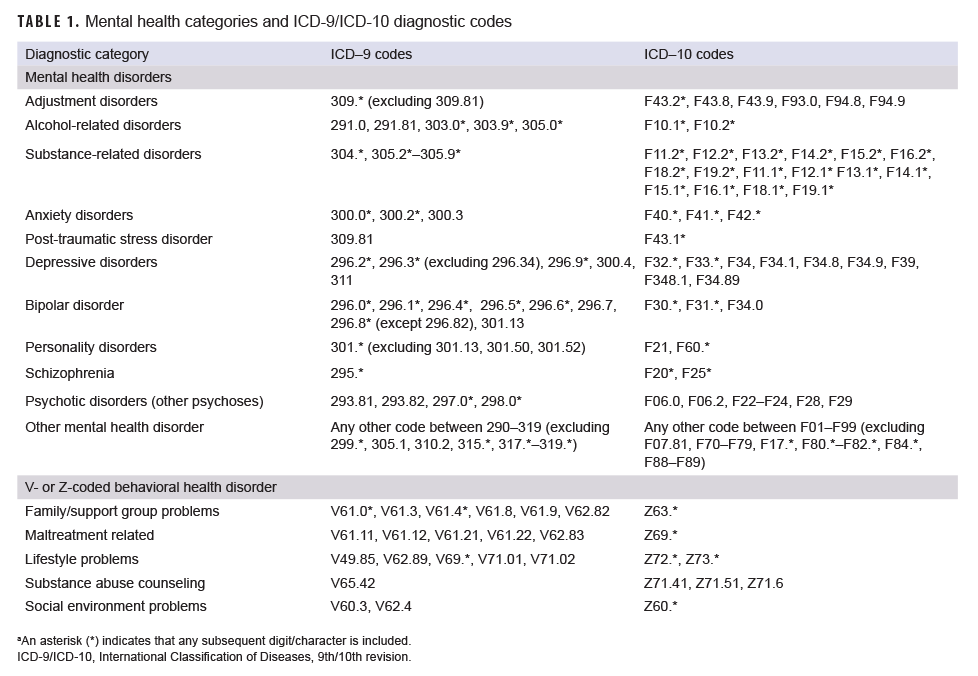

For surveillance purposes, "mental health disorders" were ascertained from records of medical encounters that included mental health disorder-specific diagnoses (ICD-9: 290–319; ICD-10: F01–F99 [Table 1]) in the first or second diagnostic position. It should be noted that although the MHS transitioned to ICD-10 on 1 October 2015, ICD-9 codes were included in this analysis because some TMDS encounters still contain ICD-9 diagnoses and ICD-9 diagnoses were needed to identify and exclude prevalent cases documented in records from before 1 October 2015. Diagnoses of pervasive developmental disorder (ICD-9: 299.*; ICD-10: F84.*), specific delays in development (ICD-9: 315.*; ICD-10: F80.*–F82.*, F88–F89), mental retardation (ICD-9: 317.*–319.*; ICD-10: F70–F79), tobacco use disorder/nicotine dependence (ICD-9: 305.1; ICD-10: F17.*), and post-concussion syndrome (ICD-9: 310.2; ICD-10: F07.81) were excluded from the analysis. Diagnoses of "mental health problems" were ascertained from records of health care encounters that included V- or Z-coded diagnoses indicative of psychosocial or behavioral health issues in the first or second diagnostic position (Table 1). "Family/support group problems" included family disruption, health problems within the family, bereavement, and other family problems; "maltreatment" included counseling and other encounters for victims or perpetrators of abuse; "lifestyle problems" included lack of exercise, high-risk sexual behavior, sleep deprivation, and other psychological or physical stress; "substance abuse counseling" included counseling encounters for substance use and abuse; and "social environment problems" included social maladjustment, social exclusion and rejection, target of (perceived) adverse discrimination and abuse, problems of adjustment to life cycle transitions, and other problems related to social environment.

Each incident diagnosis of a mental health disorder or a mental health problem was defined by a hospitalization with an indicator diagnosis in the first or second diagnostic position; 2 outpatient or TMDS visits within 180 days documented with indicator diagnoses (from the same mental health disorder or mental health problem–specific category) in the first or second diagnostic positions; or a single outpatient visit in a psychiatric or mental health care specialty setting (defined by Medical Expense and Performance Reporting System [MEPRS] code beginning with "BF") with an indicator diagnosis in the first or second diagnostic position. The case definition for schizophrenia required either a single hospitalization with a diagnosis of schizophrenia in the first or second diagnostic position or 4 outpatient or TMDS encounters with a diagnosis of schizophrenia in the first or second diagnostic position. Schizophrenia cases who remained in the military for more than 2 years after becoming incident cases were excluded as these cases were assumed to have been misdiagnosed.

Service members who were diagnosed with 1 or more mental health disorders prior to the surveillance period (i.e., prevalent cases) were not considered at risk of incident diagnoses of the same conditions during the period. Service members who were diagnosed with more than 1 mental health disorder during the surveillance period were considered incident cases in each category in which they fulfilled the case-defining criteria. Service members could be incident cases only once in each mental health disorder-specific category. Only service members with no incident mental health disorder-specific diagnoses (ICD-9: 290–319; ICD-10: F01–F99) diagnosed during or prior to the surveillance period were eligible for inclusion as cases of incident mental health problems (selected V- or Z-codes).

Results

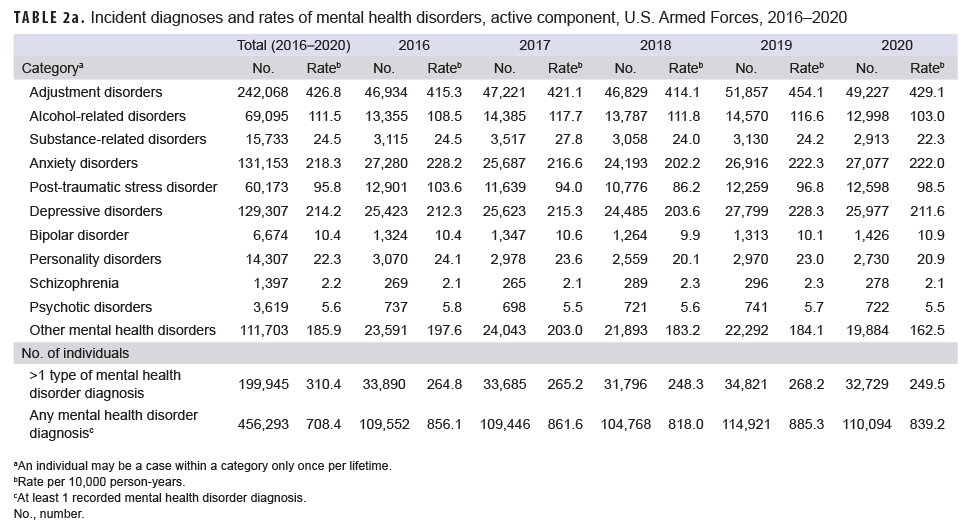

During the 5-year surveillance period, 456,293 active component service members were diagnosed with at least 1 mental health disorder; of these individuals, 199,945 (43.8%) were diagnosed with mental health disorders in more than 1 diagnostic category (Table 2a). Overall, there were 785,229 incident diagnoses of mental health disorders in all diagnostic categories. Annual numbers and rates of incident diagnoses of at least 1 mental health disorder decreased from 856.1 cases per 10,000 person-years (p-yrs) in 2016 to 818.0 cases per 100,000 p-yrs in 2018, peaked at 885.3 cases per 100,000 p-yrs in 2019, and then decreased to 839.2 cases per 100,000 p-yrs in 2020.

Over the entire period, 94.7% of all incident mental health disorder diagnoses were attributable to adjustment disorders (n=242,068; 30.8%), anxiety disorders (n=131,153; 16.7%), depressive disorders (n=129,307; 16.5%), "other" mental health disorders (n=111,703; 14.2%); alcohol-related disorders (69,095; 8.8%), and PTSD (60,173; 7.7%) (Table 2a). In comparison, relatively few incident diagnoses were attributable to substance-related disorders (n=15,733; 2.0%), personality disorders (14,307; 1.8%), bipolar disorder (6,674; 0.8%), psychotic disorders (3,619; 0.5%), and schizophrenia (1,397; 0.2%).

It was common for individuals who were diagnosed with alcohol- or substance-related disorders to also be diagnosed with other mental health disorders during the period. Among individuals who were diagnosed with alcohol-related disorders, 37.6% were also diagnosed with incident adjustment disorder and 27.6% with depressive disorder (data not shown). Among those diagnosed with substance-related disorders, 50.2% were diagnosed with alcohol-related disorders and 38.9% were diagnosed with adjustment disorders (data not shown). Adjustment disorders, depressive disorders, and personality disorders were also common co-occurring conditions. Among those diagnosed with personality disorders, 59.4% were also diagnosed with incident adjustment disorders and 51.9% were also diagnosed with incident depressive disorders (data not shown).

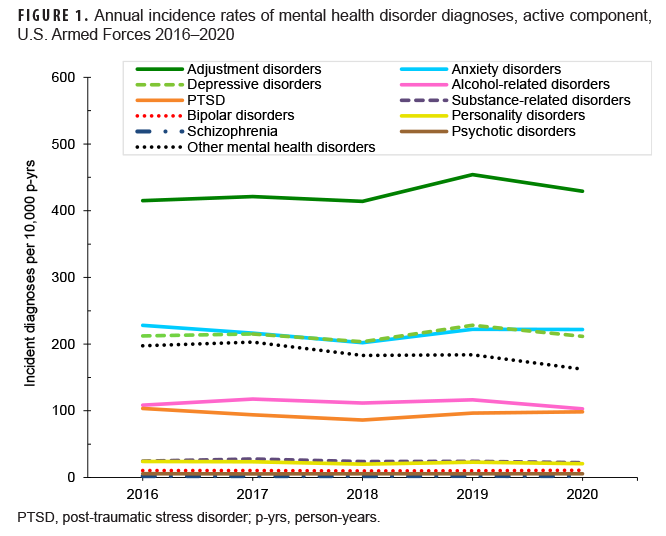

Crude annual rates of incident diagnoses of adjustment disorders, anxiety disorders, and depressive disorders followed a general pattern of decreasing or remaining stable from 2016 through 2018, increasing in 2019, and then decreasing or remaining stable in 2020 (Table 2a, Figure 1). Annual incidence of PTSD decreased during 2016 through 2018 but then increased through 2020. Rates of "other" mental health disorders decreased from 2017 through 2020. In contrast, crude annual incidence rates of diagnoses of alcohol-related disorders, substance-related disorders, personality disorders, bipolar disorders, psychotic disorders, and schizophrenia remained relatively stable through the surveillance period (Table 2a, Figure 1).

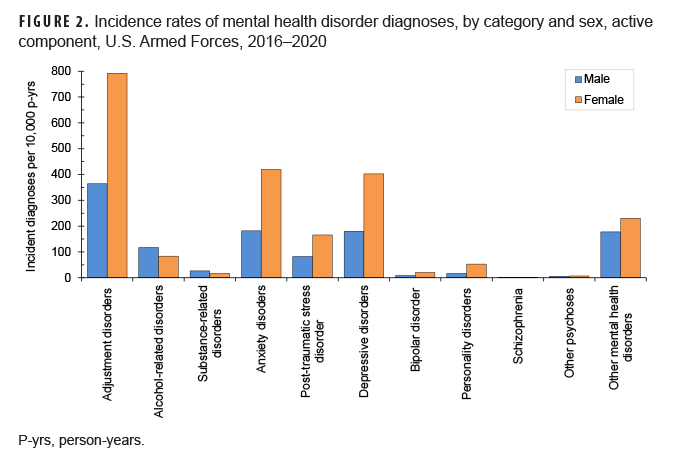

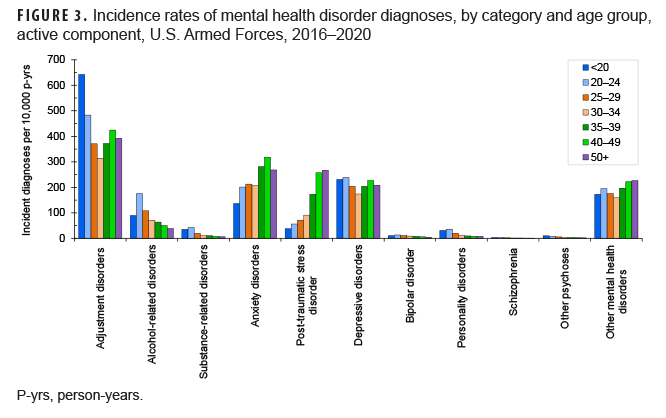

In general, overall rates of most incident mental health disorder diagnoses were higher among female than male service members. Exceptions were for schizophrenia, for which rates were similar between the sexes and alcohol- and substance-related disorders for which rates were higher among male service members (Figure 2). Rates of most mental health disorder diagnoses declined with increasing age (Figure 3). In particular, crude overall incidence rates of adjustment and psychotic disorders were higher among the youngest (less than 20 years old) service members, compared to any older age group. Rates of alcohol- and substance-related disorders, depressive disorders, bipolar disorders, personality disorders, and schizophrenia were highest among service members aged 20–24 years (Figure 3). In contrast, the rates of PTSD, anxiety disorders, and "other" mental health disorders were highest among service members in their 40s and 50s.

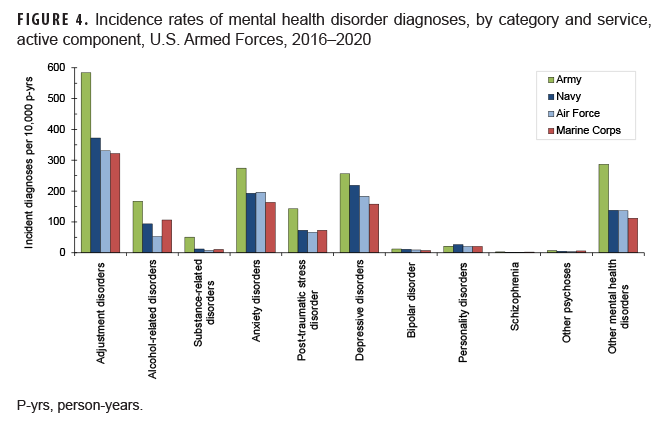

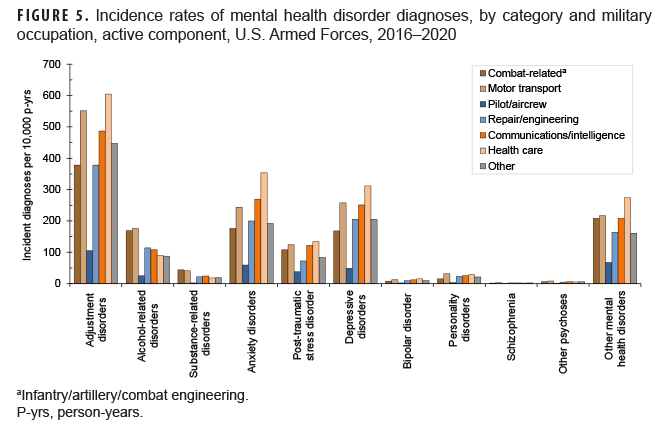

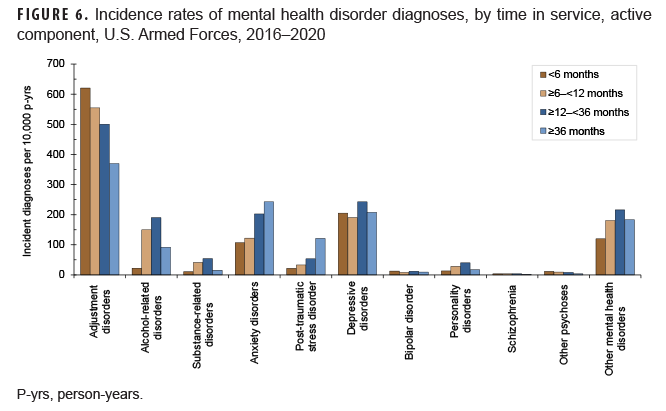

Overall incidence rates of all mental health disorders were higher in the Army than in any of the other services except for personality disorders, which were higher in the Navy (Figure 4). Crude incidence rates for alcohol-related disorders, personality disorders, schizophrenia, and other psychotic disorders were higher among those in motor transport occupations than any other category of occupation (Figure 5). In contrast, crude overall incidence rates of adjustment disorders, anxiety disorders, PTSD, depressive disorders, bipolar disorders, and "other" mental health disorders were highest among those in health care occupations. There were some differences in rates of mental health disorder diagnoses by time in service. Rates of adjustment disorders, psychotic disorders, and bipolar disorders were highest during the first 6 months of military service, whereas rates of PTSD and anxiety disorders were highest among those with at least 36 months of service (Figure 6). However, rates of all other mental health disorders were highest between 12 and 36 months of service. Finally, rates of incident anxiety disorders, PTSD, and "other" mental health disorders were higher among service members who had ever deployed to a U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM) area of responsibility (AOR) (data not shown).

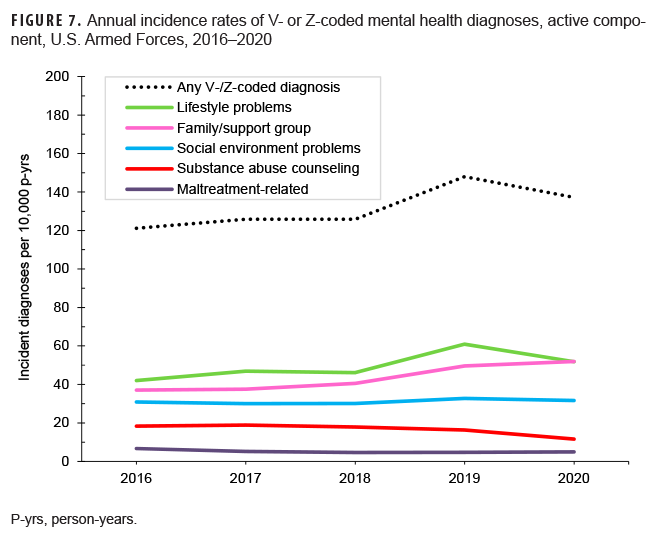

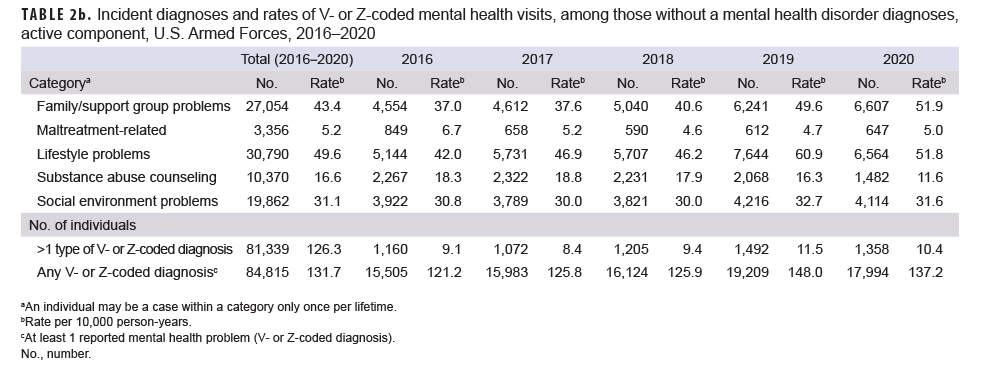

During the surveillance period, there were 91,432 records documenting mental health problems related to family/support group problems, maltreatment, lifestyle problems, or substance abuse counseling (documented with ICD-9 and ICD-10 V- and Z-codes, respectively) among 84,815 active component members who were never diagnosed with a mental health disorder (ICD-9: 290–319; ICD-10: F01–F99) (Table 2b). During the period, one-third (33.7%) of all incident reports of these mental health problems were related to lifestyle problems; almost one-third (29.6%) were related to family/support group problems; slightly more than one-fifth (21.7%) were related to social environment problems; 11.3% were related to substance abuse counseling; and 3.7% were related to maltreatment (i.e., counseling and encounters for victims or perpetrators of abuse) (Table 2b).

Crude annual rates of any V- or Z-coded mental health problems were relatively stable from 2016 through 2018, increased in 2019, and then decreased slightly in 2020 (Figure 7). The increase between 2018 and 2019 was primarily driven by lifestyle problems and family/support group problems. Rates of substance abuse counseling decreased steadily from 2017 through 2020, whereas maltreatment-related problems decreased from 2016 to 2018 and then remained relatively stable in 2019 and 2020. Overall incidence of family/support group problems and maltreatment-related problems were higher among Army members, female service members, non-Hispanic Black service members, those aged 20–24 years, enlisted members, those in motor transport occupations, and those who were in service for 12–36 months (data not shown). Overall incidence of lifestyle problems had similar demographic patterns with the exception that incidence was higher among males compared to females (data not shown). Incidence of substance abuse counseling was highest among Air Force members, male service members, those aged 20–24 years, non-Hispanic Black service members, those in repair/engineering occupations, and those who were in service for 6–12 months(data not shown). Finally, overall incidence of social environment problems was highest among Army members, female service members, non-Hispanic Black service members, those less than 20 years of age, those in motor transport occupations, and those who were in service for less than 6 months (data not shown).

Editorial Comment

This report provides an update on incident diagnoses for mental health disorders among active component service members of the U.S. Armed Forces. Similar to previous MSMR reports, rates of most incident mental health disorders were generally higher among female than male service members and among Army members, but rates declined with increasing age.2,3 In addition, adjustment disorders were the most commonly diagnosed incident mental health disorder, and anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, alcohol-related disorders, and "other" mental health disorders were also relatively common.2,3 The data presented here demonstrate a continuation of the trends in crude incidence of mental health disorders from 2007 to 2016, in which trends for many mental health disorder categories remained relatively stable during the 2016 to 2020 surveillance period. Of note, the drop in crude incidence of any mental health disorder diagnoses from 2019 through 2020 was a reversal of an increasing trend observed between 2018 and 2019.

The relative stability in rates of incident mental health disorder diagnoses observed during the surveillance period is likely related to reduced combat operations as well as prior and ongoing Department of Defense (DOD) anti-stigma campaigns. There was a significant reduction of U.S. Armed Forces in Iraq from 2011 through 2016, with an official end to combat operations in Afghanistan at the end of 2014. In this report and in several previous studies, mental health disorders such as anxiety and PTSD have been found to be significantly higher among service members with histories of deployment to a CENTCOM AOR, and the relative stability in mental health disorder diagnoses could be related to low and stable levels of deployment and combat exposure during this period.8,9 DOD anti-stigma campaigns such as the "Real Warriors" campaign launched in 2009, seek to encourage individuals to seek treatment and link service members and their families to care and other confidential resources.10

The decrease in incidence of mental health disorder diagnoses between 2019 and 2020 corresponds with the beginning of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, which was declared an international pandemic on 11 March 2020. This decreasing trend is somewhat unexpected, given that multiple studies reported negative mental health impacts of the pandemic, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports of increases in adverse mental health conditions associated with COVID-19.11,12 However, the decrease may instead be related to service members choosing to defer care due to the pandemic, which was a trend observed in the U.S. population.13 This is of particular concern given that the number of active component suicide deaths have been increasing steadily over the past 5 years, and increased 10% between 2019 and 2020, from 350 to 385 deaths according to quarterly reports from the Defense Suicide Prevention Office.14 Therefore, the trends observed in the present study warrant further investigation to determine whether they are related to a true decrease in mental health disorders or changes in health care seeking behavior, and whether service members are receiving needed mental health care services particularly during the pandemic.

Incidence of any V- or Z-coded mental health problem followed the same general trend as incident mental health disorder diagnosis rates, remaining relatively stable but with an increase in 2019 followed by a decline in 2020. The reasons for this trend may be related to the factors previously described regarding trends in mental health disorder diagnoses. These mental health problems are important to monitor as they may serve as early indicators for mental health disorders and may also act as indicators for social determinants of mental health. In particular, the World Health Organization (WHO) has described social determinants of mental health as a framework that requires understanding risk and protective factors of mental health at different levels including the individual, family, community, and society.15

There are significant limitations to this report that should be considered when interpreting the results. For example, incident cases of mental health disorders and mental health problems were ascertained from ICD-9-/ICD-10-coded diagnoses that were reported on standardized administrative records of outpatient clinic visits and hospitalizations. Such records are not completely reliable indicators of the numbers and types of mental health disorders and mental health problems that actually affect military members. For example, the numbers reported here are underestimates to the extent that affected service members did not seek care or received care that is not routinely documented in records that were used for this analysis (e.g., private practitioner, counseling or advocacy support center, chaplains); that mental health disorders and mental health problems were not diagnosed or reported on standardized records of care; and/or that some indicator diagnoses were miscoded or incorrectly transcribed on the centrally transmitted records.

On the other hand, some conditions may have been erroneously diagnosed or miscoded as mental health disorders or mental health problems (e.g., screening visits). The accuracy of estimates of the numbers, natures, and rates of illnesses and injuries of surveillance interest depend to a great extent on specifications of the surveillance case definitions that are used to identify cases. If case definitions with different specifications were used to identify cases of nominally the same conditions, the resultant estimates of numbers, rates, and trends might vary from those reported here. In addition, the analyses reported here summarize the experiences of individuals while they were serving in an active component of the U.S. military; as such, the results do not include mental health disorders and mental health problems that affected members of reserve components or veterans of recent military service who received care outside of the MHS.

Although the incidence of mental health disorders has remained relatively stable in the past 5 years, mental health disorders continue to affect a large number of service members and account for a significant burden of medical care. Ongoing efforts to assist and treat service members should continue to promote help-seeking behavior to improve the psychological and emotional well-being of service members in the U.S. Armed Forces.

References

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Division. Absolute and relative morbidity burdens attributable to various illnesses and injuries, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2020. MSMR. 2021;28(6):2–9.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center. Mental disorders and mental health problems, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2000–2011. MSMR. 2012;19(6):11–17.

- Stahlman, S and Oetting AA. Mental health disorders and mental health problems, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2007–2016. MSMR. 2018;25(3):2–11.

- Garvey Wilson A, Messer S, Hoge C. U.S. military mental health care utilization and attrition prior to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2009;44(6):473–481.

- Kritikos TK, Comer JS, He M, et al. Combat experience and posttraumatic stress symptoms among military-serving parents: a meta-analytic examination of associated offspring and family outcomes. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2019;47(1):131–148.

- Skopp N, Trofimovich L, Grimes J, et al. Relations between suicide and traumatic brain injury, psychiatric diagnoses, and relationship problems, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2001–2009. MSMR. 2012; 19(2):7–11.

- Rupp BL, Ying S, and Stahlman S. Psychiatric medical evacuations in individuals with diagnosed pre-deployment family problems, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2002–2014. MSMR. 2018; 25(10):9–15.

- Vasterling JJ, Proctor SP, Friedman MJ, et al. PTSD symptom increases in Iraq-deployed soldiers: Comparison with nondeployed soldiers and associations with baseline symptoms, deployment experiences, and postdeployment stress. J Traum Stress. 2010;23(1):41–51.

- Hoge CW, Auchterlonie JL, Milliken CS. Mental health problems, use of mental health services, and attrition from military service after returning from deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. JAMA. 2006;295(9):1023–1032.

- Real Warriors Campaign. Accessed 31 July 2021. https://www.health.mil/Military-Health-Topics/Centers-of-Excellence/Psychological-Health-Center-of-Excellence/Real-Warriors-Campaign

- Xiong J, Lipsitz O, Nasri F, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:55–64.

- Czeisler MÉ, Lane RI, Petrosky E, et al. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 Pandemic - United States, June 24-30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(32):1049–1057.

- Czeisler MÉ, Marynak K, Clarke KEN, et al. Delay or avoidance of medical care because of COVID-19-related concerns - United States, June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(36):1250–1257.

- Department of Defense (DoD) Quarterly Suicide Report (QSR) 1st Quarter, CY 2021. Accessed 31 July 2021. https://www.dspo.mil/QSR/

- World Health Organization and Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation. Social determinants of mental health. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2014.