What are the new findings?

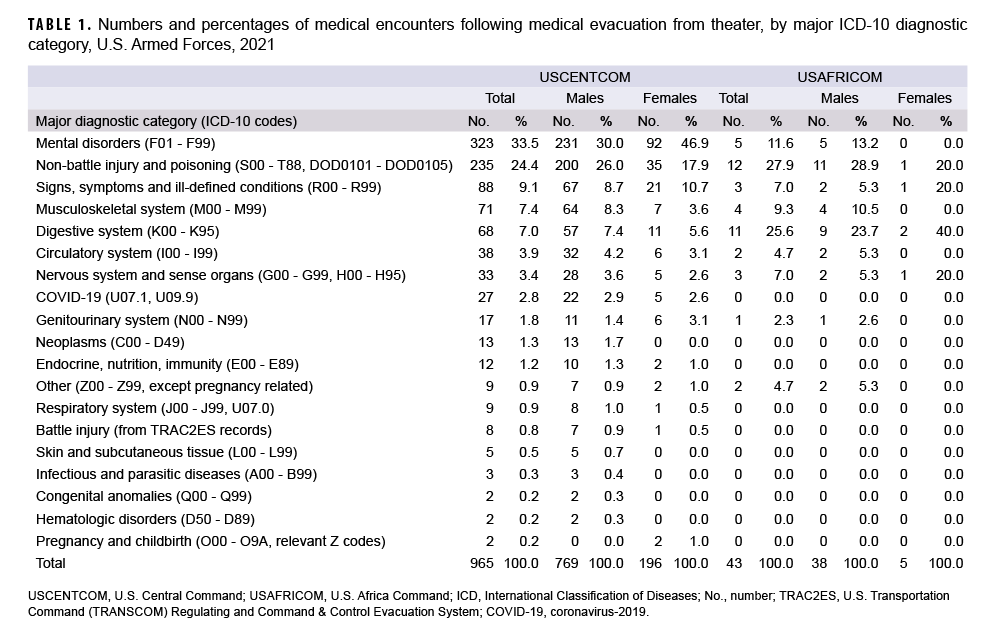

The proportions of evacuations out of USCENTCOM that were due to battle injuries declined substantially in 2021. For USCENTCOM, evacuations for mental health disorders were the most common, followed by non-battle injury and poisoning, and signs, symptoms, and ill-defined conditions. For USAFRICOM, evacuations for non-battle injury and poisoning were most common, followed by disorders of the digestive system and mental health disorders.

What is the impact on readiness and force health protection?

Only 965 service members were evacuated out of USCENTCOM and 43 out of USAFRICOM during 2021, but the process of medical evacuation of service members to Europe and CONUS is logistically demanding. The effort expended to evacuate service members to sources of definitive, modern health care is a reassuring investment in the health, welfare, and importance of the men and women serving overseas.

In recent years, there have been substantial reductions in U.S. Central Command (USCENTCOM) area of responsibility (AOR) combat operations in Southwest Asia, with the U.S. completing withdrawal from Afghanistan on 31 August 2021 and ending its combat mission in Iraq on 9 December 2021.1,2 However, the number of service members deployed to the USCENTCOM AOR remains significant, with an estimated 40,000–60,000 troops deployed to 21 different countries.3 In contrast, approximately 6,000 troops including civilians and contractors are deployed to the U.S. Africa Command (USAFRICOM), which includes all countries on the African continent except for Egypt (which is part of USCENTCOM).4 Despite this relatively small number of deployed troops, the U.S. has increased operations in some African countries as the combat missions in Iraq and Afghanistan have come to a close, and both USAFRICOM and USCENTCOM remain important AORs for counterterrorism efforts.4,5

In theaters of operation, most medical care is provided by deployed military medical personnel; however, some injuries and illnesses require medical management outside the operational theater. In these cases, the affected individuals are usually transported by air to a fixed military medical facility in Europe or the U.S. where the service members receive the specialized, technically advanced, and/or prolonged diagnostic, therapeutic, and rehabilitative care required. Medical air transports, or medical evacuations, are costly and generally indicative of serious medical conditions. Some serious conditions are directly related to participation in or support of combat operations (e.g., battle wounds); however, many other conditions are unrelated to combat and may be preventable. This report summarizes the natures, numbers, and trends of conditions for which male and female military members were medically evacuated out of USCENTCOM or USAFRICOM AOR operations during 2021 and provides historical comparisons to the previous 4 years.

Methods

The surveillance period was 1 January 2017 through 31 December 2021. The surveillance population included all members of the active and reserve components of the U.S. Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps who were deployed to the USCENTCOM or USAFRICOM AOR during the period. Medical evacuations conducted by the U.S. Transportation Command (TRANSCOM) from the USCENTCOM or USAFRICOM AOR to a medical treatment facility outside the operational theater were assessed from records maintained in the TRANSCOM Regulating and Command & Control Evacuation System (TRAC2ES). Inclusion criteria for this analysis stipulated that the medical evacuee have at least 1 inpatient or outpatient medical encounter in a permanent military medical facility in the U.S. or Europe during a time interval extending from 5 days before to 10 days after the reported evacuation date. Data for evacuations out of USCENTCOM and USAFRICOM are presented separately.

Medical evacuations included in the analyses were classified by the causes and natures of the precipitating medical conditions (based on information reported in relevant evacuation and medical encounter records). First, all medical conditions that resulted in evacuations were classified as either “battle injuries” or “non-battle injuries and illnesses” (based on entries in an indicator field of the TRAC2ES evacuation record). Evacuations due to non-battle injuries and illnesses were subclassified into 18 illness/injury categories based on International Classification of Diseases, 9th and 10th Revisions (ICD-9 and ICD-10, respectively) diagnostic codes reported on the records of medical encounters after evacuation, including 1 category specific to diagnosis of COVID-19 or a post- COVID-19 condition (ICD-10: U07.1 or U09.9).

For the purposes of this report, all records of hospitalizations and ambulatory visits from 5 days before to 10 days after the reported date of each medical evacuation were identified. In most cases, the primary (first-listed) diagnosis for either a hospitalization (if any occurred) or the earliest ambulatory visit after evacuation was considered indicative of the condition responsible for the evacuation. However, if the first-listed diagnostic code specified the external cause (rather than the nature) of an injury (ICD-9 E-code/ICD-10 V-, W-, X-, or Y-code) or an encounter for something other than a current illness or injury (e.g., observation, medical examination, or vaccination [ICD-9 V-codes/ICD-10 Z-codes other than those related to pregnancy]), then secondary diagnoses that specified illnesses and injuries (ICD-9: 001–999/ICD-10: A00–T88, U07.0, U07.1, or U09.9) were considered the likely reasons for the subject evacuations. If there was no secondary diagnosis or if the secondary diagnosis also was an external cause code, the first-listed diagnostic code of a subsequent encounter was used.

The disposition codes associated with the medical encounter were classified to document a disposition category for each medical evacuation. Inpatient disposition categories include: returned to duty (code 01), transferred/discharged to other facility (codes 02–04, 09, 21–28, 43, or 61–66), died (codes 20, 30, 40–42, 50, or 51), separated from service (codes 10–15), and other/unknown. Outpatient disposition categories include: released without limitation (code 1), released with work/duty limitation (code 2), immediate referral (code 4), sick at home/quarters (codes 3 or S), admitted/ transferred to civilian hospital (codes 7, 9, A–D, or U), died (codes 8 or G), discharged home (code F), and other/unknown.

Results

In 2021, a total of 965 medical evacuations of service members from the USCENTCOM AOR and 43 from the USAFRICOM AOR were followed by at least 1 medical encounter in a fixed medical facility outside the operational theater (Table 1). For USCENTCOM, there were more medical evacuations for mental health disorders (n=323; 33.5%) than for any other single category of illnesses or injuries. In order of decreasing frequency, the categories with the next most common medical evacuations were non-battle injuries and poisonings (n=235; 24.4%); signs, symptoms, and ill-defined conditions (n=88; 9.1%); musculoskeletal system/connective tissue disorders (n=77; 7.4%); and disorders of the digestive system (n=68; 7.0%). In USAFRICOM, medical evacuations for non-battle injuries and poisonings (n=12; 27.9%) were most common, followed by disorders of the digestive system (n=11; 25.6%) and mental health disorders (n=5; 11.6%). There were only 8 (0.8%) medical evacuations for battle injuries from USCENTCOM and there were 0 evacuations for battle injuries from USAFRICOM. The top 3 categories for USCENTCOM—mental health disorders (most frequently adjustment and depressive disorders); non-battle injuries (primarily fractures of extremities, dislocations, strains, and sprains); and signs, symptoms, and illdefined conditions (such as syncope and collapse, abnormalities of heartbeat, localized swelling, etc.)—accounted for twothirds (66.9%) of all evacuations (Table 1). Similarly in USAFRICOM, the top 3 categories— non-battle injuries (most frequently shoulder and upper arm injuries); disorders of the digestive system (e.g., inguinal hernias, appendicitis, and other diseases); and mental health disorders accounted for almost two-thirds (65.1%) of all evacuations.

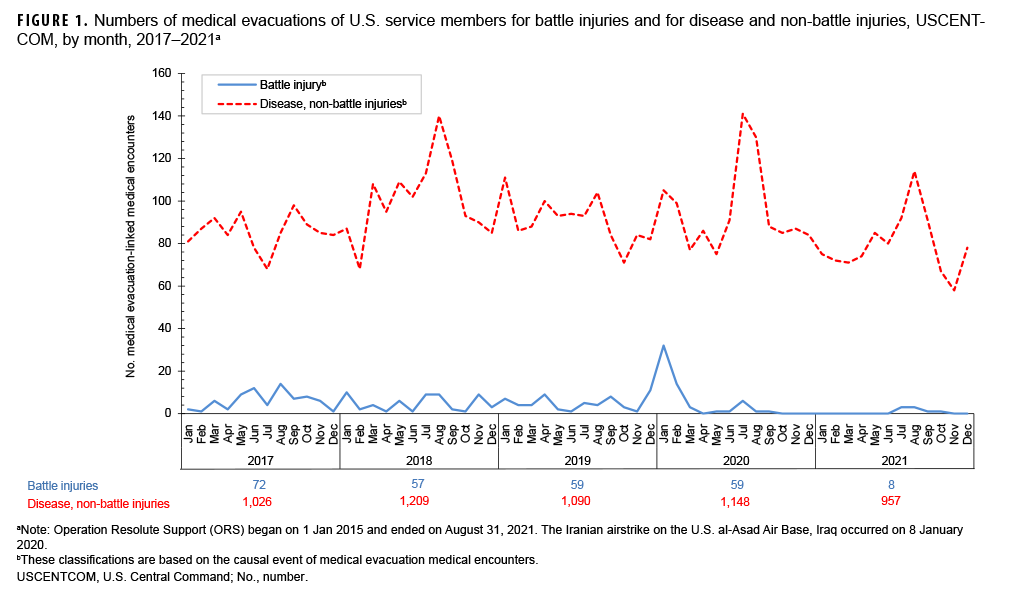

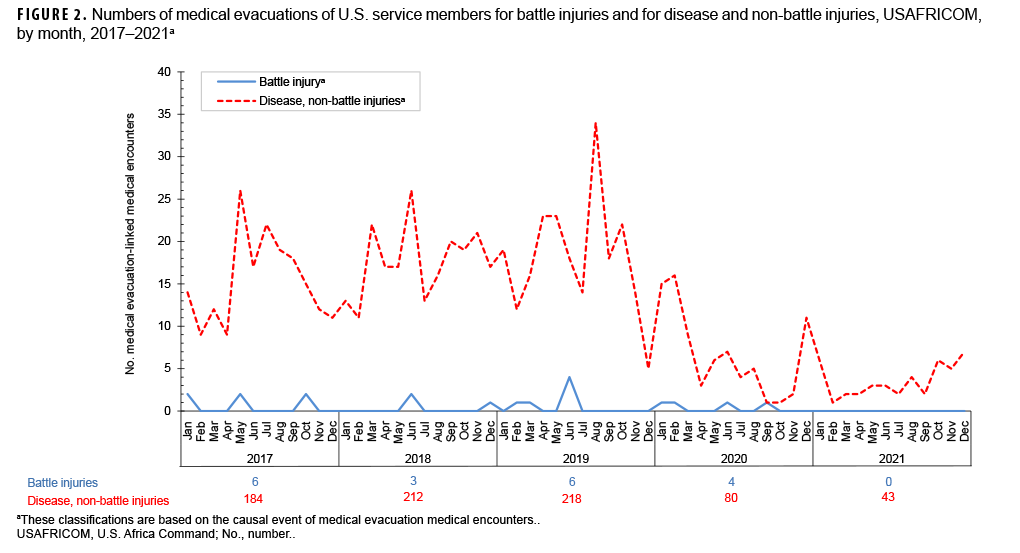

During 2017–2021, the annual number of medical evacuations out of USCENTCOM attributable to battle injuries was highest in 2017 (n=72), decreased in 2018 (n=57), remained relatively stable through 2020 (n=59), and then decreased substantially in 2021 (n=8) (Figure 1). There was a peak in the monthly number of medical evacuations out of USCENTCOM attributable to battle injuries in January 2020 (n=32) (Figure 1). The annual number of medical evacuations out of USCENTCOM attributable to non-battle injuries and diseases fluctuated between 957 and 1,209 during the 2017–2021 surveillance period. For USAFRICOM, the annual number of medical evacuations attributable to battle injuries ranged from 3 to 6 during the first 4 years of the surveillance period but then decreased to 0 in 2021 (Figure 2). The annual number of medical evacuations out of USAFRICOM attributable to non-battle injuries and diseases peaked in 2019 (n=218) and decreased through 2021 (n=43).

Demographic and military characteristics

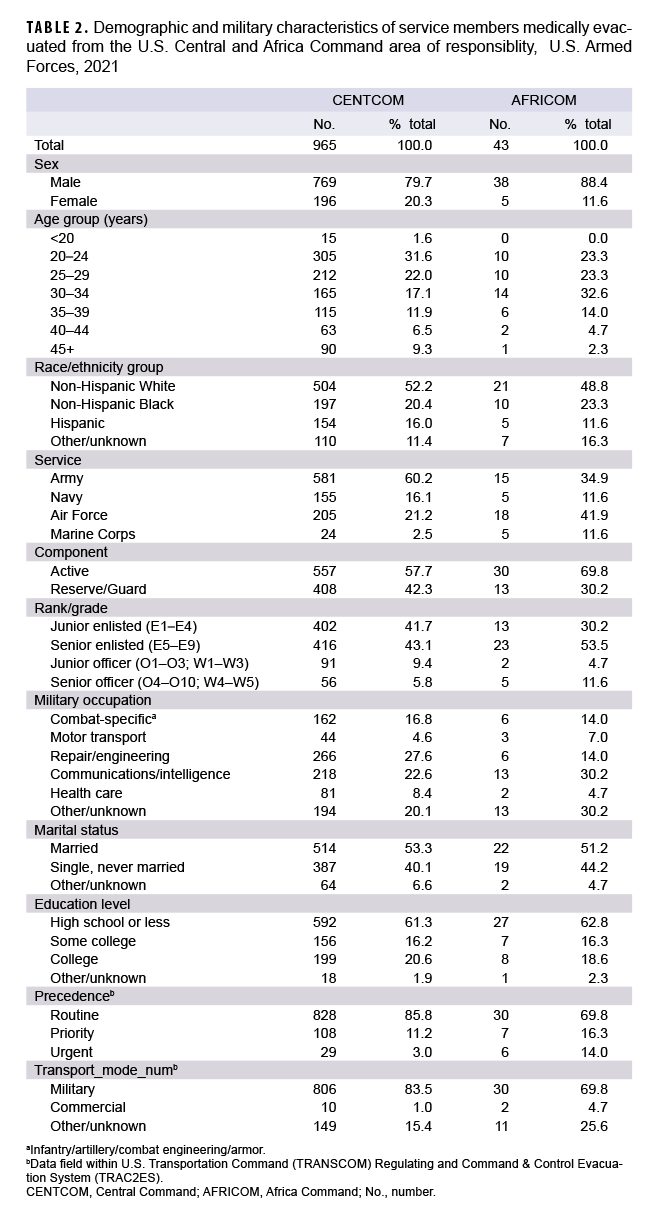

The percentage of medical evacuations in 2021 was higher among male than female service members for both USAFRICOM (88.4% vs. 11.6%) and USCENTCOM (79.8% vs. 20.3%) (Table 1, 2). The most frequent causes of medical evacuations out of USCENTCOM among male service members were mental health disorders (n=231; 30.0%); non-battle injury and poisoning (n=200; 26.0%); and signs, symptoms, and ill-defined conditions (n=67; 8.7%) (Table 1). Similarly, among female service members, the most frequent causes of medical evacuations were mental health disorders (n=92; 46.9%); non-battle injury and poisoning (n=35; 17.9%); and signs, symptoms, and illdefined conditions (n=21; 10.7%). The most frequent causes of medical evacuations out of USAFRICOM among male service members were non-battle injury and poisoning (n=11; 28.9%); digestive system disorders (n=9; 23.7%); and mental health disorders (n=5; 13.2%). There were only 5 medical evacuations out of USAFRICOM among female service members in 2021.

Compared to males, female service members had notably higher percentages of medical evacuations out of USCENTCOM for mental health disorders and genitourinary system disorders (Table 1). In contrast, male service members had higher percentages of evacuation out of USCENTCOM for non-battle related injuries, musculoskeletal system disorders, and digestive system conditions.

Within the various demographic and military characteristics of those service members who were evacuated, the largest numbers and proportions of evacuees out of USCENTCOM were among non-Hispanic White service members, those aged 20–24 years, members of the Army, junior and senior enlisted personnel, and those in repair/engineering occupations (Table 2). The largest numbers and proportions of evacuees out of USAFRICOM were among non-Hispanic White service members, those aged 30–34 years, members of the Air Force, senior enlisted personnel, and those in communications/intelligence or other or unknown occupations. In 2021, most medical evacuations out of USCENTCOM (85.8%) and USAFRICOM (69.8%) were characterized as having routine precedence. The remainder of evacuations had priority (11.2% USCENTCOM; 16.3% USAFRICOM) or urgent (3.0% USCENTCOM; 14.0% USAFRICOM) precedence. Most medical evacuations were accomplished through military transport (83.5% USCENTCOM; 69.8% USAFRICOM) (Table 2).

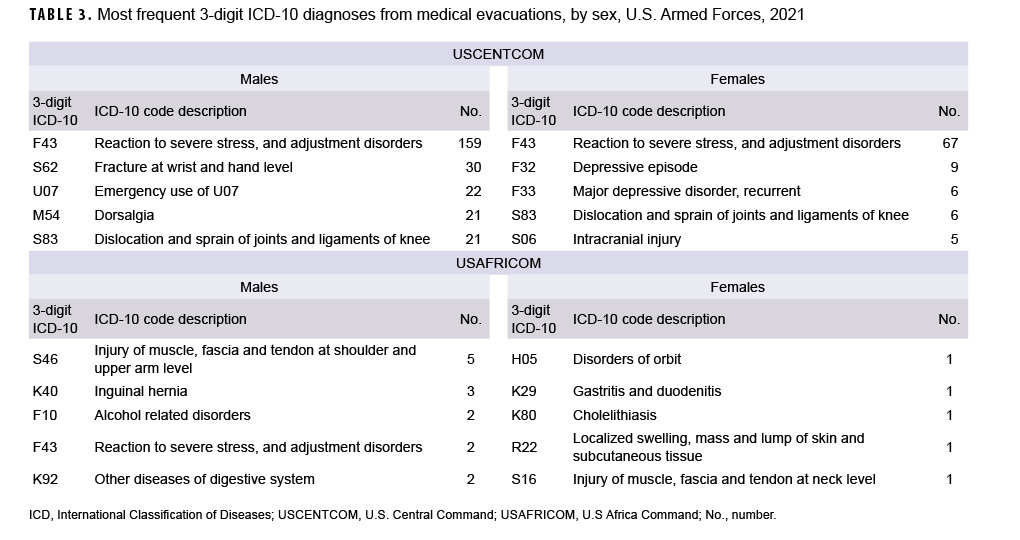

Most frequent specific diagnoses

Among both male and female service members medically evacuated out of USCENTCOM in 2021, a mental health disorder (“reaction to severe stress, and adjustment disorders”) was the most frequent specific diagnosis (3-digit ICD-10 diagnosis code: F43) during initial medical encounters after evacuations (Table 3). The next most common 3-digit diagnoses for male service members were fractures at the hand and wrist level (ICD-10: S62), and COVID-19 (ICD-10: U07.1). For female service members, the second and third most common 3-digit diagnoses were for depressive episodes (ICD-10: F32) and recurrent major depressive disorder (ICD-10: F33). Among male service members medically evacuated out of USAFRICOM in 2021, “Injury of muscle, fascia and tendon at shoulder and upper arm level” was the most frequent specific diagnosis (3-digit ICD-10 diagnosis code: S46) during initial medical encounters after evacuations.

Disposition

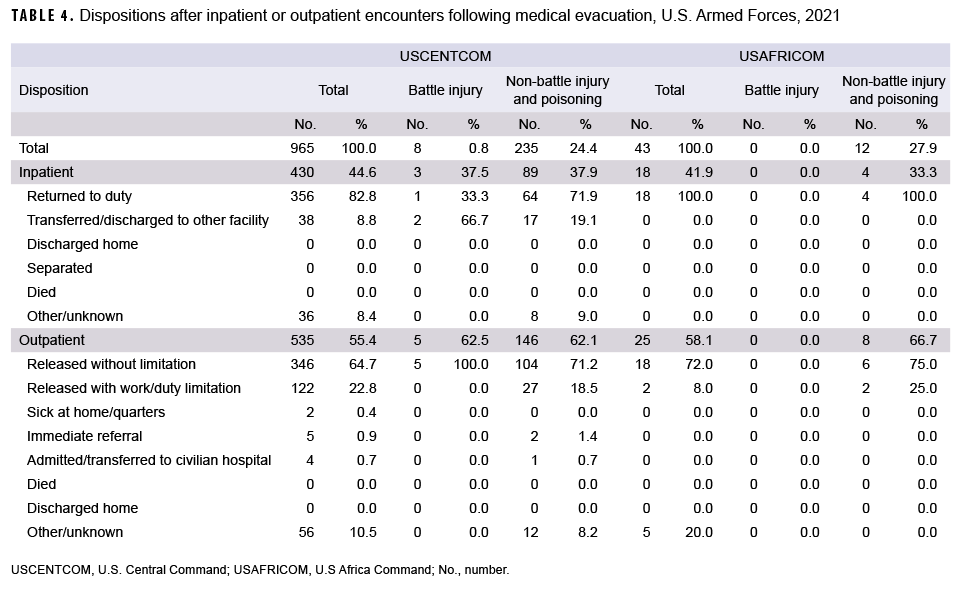

Of the 965 USCENTCOM medical evacuations and 43 USAFRICOM evacuations in 2021, a total of 430 (44.6%) out of USCENTCOM and 18 (41.9%) out of USAFRICOM resulted in inpatient encounters. About four-fifths (82.8%) of all service members who were hospitalized after medical evacuations out of USCENTCOM were discharged back to duty. All service members who were hospitalized after medical evacuations out of USAFRICOM were discharged back to duty. Less than one-tenth (8.8%) of service members who were hospitalized after medical evacuations out of USCENTCOM were transferred or discharged to other facilities (Table 4).

Among medical evacuations out of USCENTCOM, return to duty dispositions were much more likely after hospitalizations for non-battle injuries (n=64, 71.9%) than for battle injuries (n=1, 33.3%). The majority (n=2, 66.7%) of battle injury-related hospitalizations and a little more than one-fifth (n=17, 19.1%) of non-battle injury-related hospitalizations resulted in transfers/discharges to other facilities (Table 4).

Slightly more than one-half of all medical evacuations out of USCENTCOM (n=535; 55.4%) and USAFRICOM (n=25; 58.1%) resulted in outpatient encounters only. Of the service members who were treated exclusively in outpatient settings after evacuations, the majority (64.7% USCENTCOM; 72.0% USAFRICOM) were discharged back to duty without work/duty limitations or released with work/duty limitations (22.8% USCENTCOM; 8.0% USAFRICOM). Service members treated as outpatients after battle injury-related evacuations out of USCENTCOM were more likely to be released without limitations (n=5; 100%) than USCENTCOM medical evacuees treated as outpatients for non-battle injuries (n=104; 71.2%) (Table 4).

Editorial Comment

This report documented that in 2021, only 8 (0.8%) of all medical evacuations out of USCENTCOM, and 0 medical evacuations out of USAFRICOM, were associated with battle injuries. Counts of evacuations for battle injuries out of USCENTCOM decreased substantially in 2021, likely reflecting the significantly reduced amount of combat operations in the USCENTCOM AOR as compared to the prior years of Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom. However, there was a small spike in the number of medical evacuations for battle injuries in USCENTCOM in January 2020, coinciding with the Iranian ballistic missile attack on the U.S. al-Asad Air Base in Iraq.

Most evacuations out of USCENTCOM in 2021 were attributed to mental health disorders, followed by non-battle injuries and poisonings; signs, symptoms, and ill-defined conditions; and musculoskeletal disorders. Evacuations during the entire 5-year surveillance period followed a similar pattern. In USCENTCOM, during each year of the entire 5-year surveillance period, mental health disorders were the most frequent diagnosis followed by non-battle injuries; signs, symptoms and ill-defined conditions; musculoskeletal disorders; and digestive system disorders. In USAFRICOM, nonbattle injuries was the most frequent diagnosis each year of the surveillance period. Between 2017 and 2020, in terms of frequency of occurrence, non-battle injuries was followed by signs, symptoms and illdefined conditions, and mental health disorders. However, in 2021, non-battle injuries was followed by digestive system disorders and mental health disorders. In 2021, male service members had higher percentages of evacuations out of USCENTCOM for non-battle related injuries, musculoskeletal system disorders, and digestive system conditions compared to female service members. The majority of service members who were evacuated out of USCENTCOM or USAFRICOM were returned to normal duty status following their post-evacuation hospitalizations or outpatient encounters.

Overall, the changes in numbers of medical evacuations over the course of the surveillance period reflect the drawdown of combat operations in USCENTCOM and the small but increasing expansion of operations in USAFRICOM. The relatively low percentage of medical evacuations in 2021 suggests that most deployers were sufficiently healthy and ready for their deployments and received the medical care in theater necessary to complete their assignments without having to be evacuated. Moreover, the fact that very few medical evacuations were conducted for chronic conditions such as hematologic disorders and congenital anomalies also supports the idea that most deployers were sufficiently healthy for deployment. However, it is not surprising that such conditions were occasionally diagnosed among deployed service members. For example, there were 2 medical evacuations out of USCENTCOM for congenital anomalies in 2021; one for congenital diaphragmatic hernia and 1 for sinus, fistula and cyst of branchial cleft (data not shown). Because congenital anomalies may not be identified and diagnosed until later in life,6 and may also cause health issues later in life, the infrequent detection of such diagnoses during deployment is not unexpected.

The proportion of 2021 medical evacuations out of USCENTCOM attributed to mental health disorders (33.5%) represents a slight increase over the proportion reported in recent MSMR analyses of medical evacuations reported in 2020 (27.2%) and 2019 (27.1%), and considerably higher than the proportion (11.6%) reported in an earlier MSMR report examining evacuations from Iraq during a 9-year period between 2003 and 2011.7-9 However, the latter article also reported that during the last 4 years of the surveillance period (2008–2011), as the proportion of evacuations for battle injuries fell sharply, the proportions of evacuations for mental health disorders increased dramatically for both male (peak of 20.9% in 2010) and female service members (peak of 26.6% in 2010). Although some studies have indicated improved access to mental health care in deployed settings, the results from the current analysis indicate that mental health diagnoses still represent the single most common basis for medical evacuations out of the USCENTCOM AOR.10 This could be due, at least in part, to variations in the availability of mental health care in deployed settings. In these settings, the distribution of providers and clinics that deliver such services is uneven and varies according to factors such as the number of deployed personnel and the assessed needs of the particular unit.10 In addition, although the number of mental health care providers in Afghanistan increased from 2005 through 2010, this number decreased after 2013 as part of the overall drawdown of U.S. troops from the region.10

Several important limitations should be considered when interpreting the results of this analysis. Direct comparisons of numbers and percentages of medical evacuations by cause, as between male and female service members, can be misleading; for example, such comparisons do not account for differences between the groups in other characteristics (e.g., age, grade, military occupation, location, and activities while deployed) that are significant determinants of medical evacuation risk. Moreover, because data about the characteristics of the entire deployed population of service members were not available, it was not possible to determine if the members of demographic and military groups listed above were over or underrepresented among the evacuees. Also, for this report, most causes of medical evacuations were estimated from primary diagnoses that were recorded during hospitalizations or initial outpatient encounters after evacuation. In some cases, clinical evaluations in fixed medical treatment facilities after medical evacuations may have ruled out serious conditions that were clinically suspected in theater. For this analysis, the causes of such evacuations reflect diagnoses that were determined after evaluations outside of the theater rather than diagnoses—perhaps of severe disease—that were clinically suspected in theater. To the extent that this occurred, the causes of some medical evacuations may seem surprisingly minor.

Overall, the results of the current analysis highlight the continued need to tailor force health protection policies, training, supplies, equipment, and practices based on characteristics of the deployed force (e.g., combat vs. support; male vs. female) and the nature of the military operations (e.g., combat vs. humanitarian assistance).

References

- White House Briefing Room. Remarks by President Biden on the End of the War in Afghanistan. August 31, 2021. Accessed 24 March 2022. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2021/08/31/remarks-by-presidentbiden-on-the-end-of-the-war-in-afghanistan/

- Kullab, Samya. US Formally Ends Combat Mission in Iraq. Military Times. December 9, 2021. Accessed 24 March 2022. https://www.militarytimes.com/news/your-military/2021/12/09/us-formally-ends-combat-mission-in-iraq/

- Lawrence, J.P. US Troop Level Reduction in Middle East Likely as Focus Shifts Elsewhere. January 14, 2022. Accessed 24 March 2022. https://www.stripes.com/theaters/middle_east/2022-01-14/centcom-central-command-drawdown-iraq-afghanistan-kuwait-saudi-arabia-4289137.html

- Beynon, Steve. 1,000 National Guard Soldiers to Deploy to Africa as Mid East Wars Wind Down. November 29, 2021. Accessed 24 March 2022. https://www.military.com/dailynews/2021/11/29/1000-national-guard-soldiersdeploy-africa-mid-east-wars-wind-down.html

- White House Briefing Room. Letter to the Speaker of the House and President Pro Tempore of the Senate Regarding the War Powers Report. June 8, 2021. Accessed 24 March 2022. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statementsreleases/2021/06/08/letter-to-the-speaker-of-thehouse-and-president-pro-tempore-of-the-senateregarding-the-war-powers-report/

- The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and the National Center for Health Statistics. ICD-10-CM Official Guidelines for Coding and Reporting. FY 2021. Accessed 24 March 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/icd/10cmguidelines-FY2021.pdf

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center. Medical evacuations from Operation Iraqi Freedom/Operation New Dawn, active and reserve components, U.S. Armed Forces, 2003–2011. MSMR. 2012;19(2):18–21.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Division. Medical evacuations out of the U.S. Central Command, active and reserve components, U.S. Armed Forces, 2019. MSMR. 2020;27(5):27-32.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Division. Medical evacuations out of the U.S. Central Command, active and reserve components, U.S. Armed Forces, 2020. MSMR. 2021;28(5):28-33.

- United States Government Accountability Office. Report to Congressional Committees. Defense health care: DOD is meeting most mental health care access standards, but it needs a standard for follow-up appointments. April 2016. https://www.gao.gov/assets/680/676851.pdf