ABSTRACT

The COVID-19 pandemic brought with it concerns for the effects on mental health, from both the disease itself and the steps taken to combat it. Given the readiness ramifications of those effects, it is necessary to understand them as they apply to members of the U.S. Armed Forces and their families. This study aimed to analyze temporal trends in mental health-related emergency room (ER) visits before and during the COVID-19 pandemic among active duty service members (ADSMs) and dependents. A total of 5,205,259 health care visits in an ER setting between 1 January 2017 to 31 March 2021 were included. Multivariate logistic regressions showed significantly increased odds of ER visits related to mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic when compared to a 3 year period before, both among active duty service members and adult dependents (adjusted odds ratio, AOR: 1.13, 95%CI: 1.12, 1.14), and dependents under 18 years of age (AOR: 1.44, 95%CI: 1.42, 1.48). These findings document significant increases in demand for emergency mental health services during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially within younger cohorts.

What are the new findings?

During the COVID-19 pandemic, monthly emergency room (ER) visits decreased by 30% but those related to mental health increased by 24.3% among ADSMs and dependents. Dependents under 18 years of age had 1.44 times the odds of an ER visit relating to mental health during the pandemic when compared to the 3 years prior.

What is the impact on readiness and force health protection?

An increase in the frequency of ADSM and dependent populations seeking mental health care can increase the burden on military health systems and decrease readiness. Understanding the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health of both ADSMs and dependents may better prepare the U.S. Armed Forces to respond quickly should another pandemic arise.

BACKGROUND

Concerns over the psychological effects of the COVID-19 pandemic1-3 are increasing.4-8 Surveys of the general population following stay-at-home orders and social distancing precautions show increased levels of psychological distress,6,7 with 78% of respondents feeling that their mental health worsened since the outbreak.6 To date, these effects are less understood in active duty service members (ADSMs) and their family members (dependents).

Mental health disorders among the U.S. Armed Forces contribute to morbidity, health care utilization, and attrition.9-11 Therefore, it is important to fully understand the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in order to prevent, target, intervene, and mitigate negative health outcomes among ADSMs and dependents. The objective of this analysis was to evaluate temporal trends in the proportion of emergency room (ER) visits for mental health among ADSMs and dependents, in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic compared to previous years.

METHODS

This was a secondary, cross-sectional analysis using medical encounter data from the Comprehensive Ambulatory/Professional Encounter Record (CAPER) and Tricare Encounter Data, Non-Institutional (TED-NI). Visits that occurred in an ER setting from 1 January 2017 to 31 March 2021 for ADSMs or dependents aged 60 years or younger were included for this analysis. Visits generated from military hospitals and clinics that transitioned record management to Military Health System (MHS) GENESIS were excluded from the entire analysis.

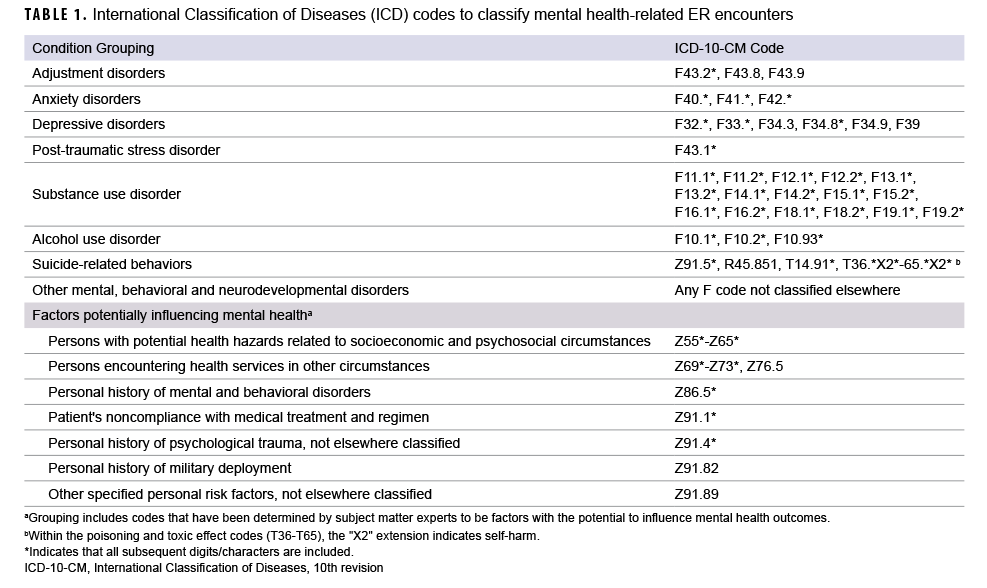

ER visits were grouped into periods as pre-COVID-19 (1 January 2017 to 29 February 2020) or during the COVID-19 pandemic (1 March 2020 to 31 March 2021). Mental health-related ER visits, the outcome of interest, were defined by the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes indicating diagnosis for disorders related to adjustment, anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress, substance or alcohol use, suicide-related behaviors, other mental, behavioral and neurodevelopmental disorders, or a visit documenting specific symptoms or factors potentially influencing mental health (Table 1). Mental, behavioral, and neurodevelopmental disorders outside the 6 specific disorder categories listed above were pooled into an additional category designated “other,” as these codes reflect a wide-ranging number of disorders but are still applicable to the intended objective of this study. The selected codes for symptoms or factors potentially influencing mental health included visits with documentation of potential hazards related to socioeconomic and psychosocial circumstances (e.g., problems related to employment, housing and economic circumstances, psychosocial circumstances, etc.); visits for mental health services for other circumstances such as abuse, sexual behavior/orientation, lifestyle, and life management; personal history of mental and behavioral disorders; patient non-compliance with a medical treatment regimen; personal history of psychological trauma; personal history of military deployment; and other specified personal risk factors, not elsewhere classified. The specific ICD-10 codes and groupings were selected based on guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC),12 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V),13 and advice from Navy behavioral health providers.

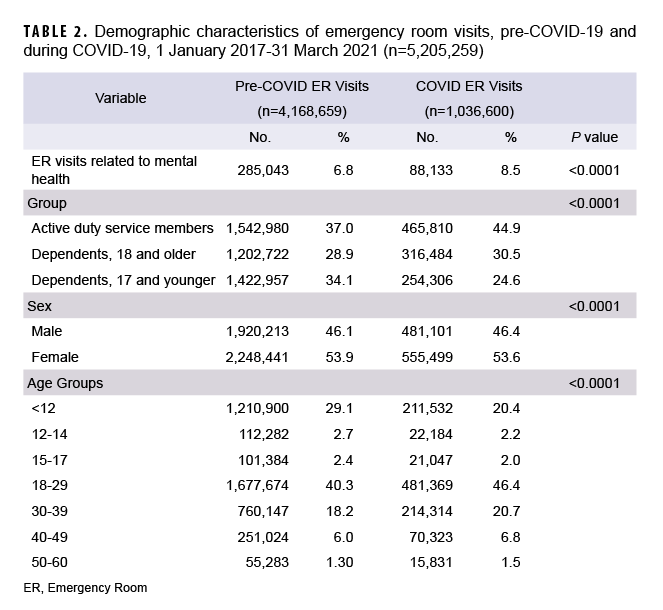

Demographic characteristics were analyzed and compared for ER visits taking place before and during the COVID-19 pandemic period, displayed in frequencies and tested for significance using a chi-square test. Data were stratified into three groups: ADSMs, dependents ages 18 years and older, and dependents less than 18 years of age. A multivariate logistic regression was used to explore the differences between the periods before and during the COVID-19 pandemic with respect to ER visits related to mental health, accounting for relevant demographic variables. Results were reported as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals. This regression analysis was stratified into two models: 1 for adults (ADSMs and dependents ages 18 years and older) and 1 for dependents under 18 years of age. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc.).

RESULTS

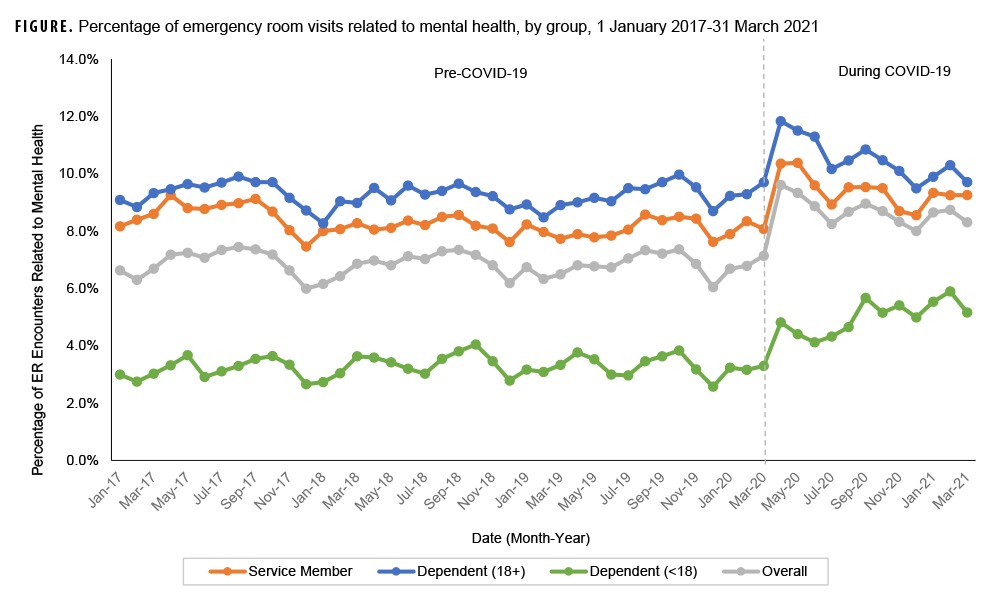

Overall, 5,205,259 ER visits for all causes were included in this analysis, 20% of which occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic. Average monthly ER visits (for any cause) decreased from 109,702 before the pandemic to 79,739 during the COVID-19 pandemic, representing a 27% decrease in monthly visits (data not shown). The proportion of ER visits within the adult population increased during the pandemic, with a higher percentage from ADSMs (Table 2). Monthly ER visits related to mental health averaged 7,502 visits pre-COVID-19 and dropped to an average of 6,780 during the pandemic, representing a 10% decrease (data not shown). Despite this decrease, the proportion of all ER visits related to mental health saw a relative increase of 11.4% among ADSMs, 12.2% among dependents 18 years of age and older, and 48.4% among dependents less than 18 years of age, with an upward monthly trend throughout the COVID-19 timeframe (Figure).

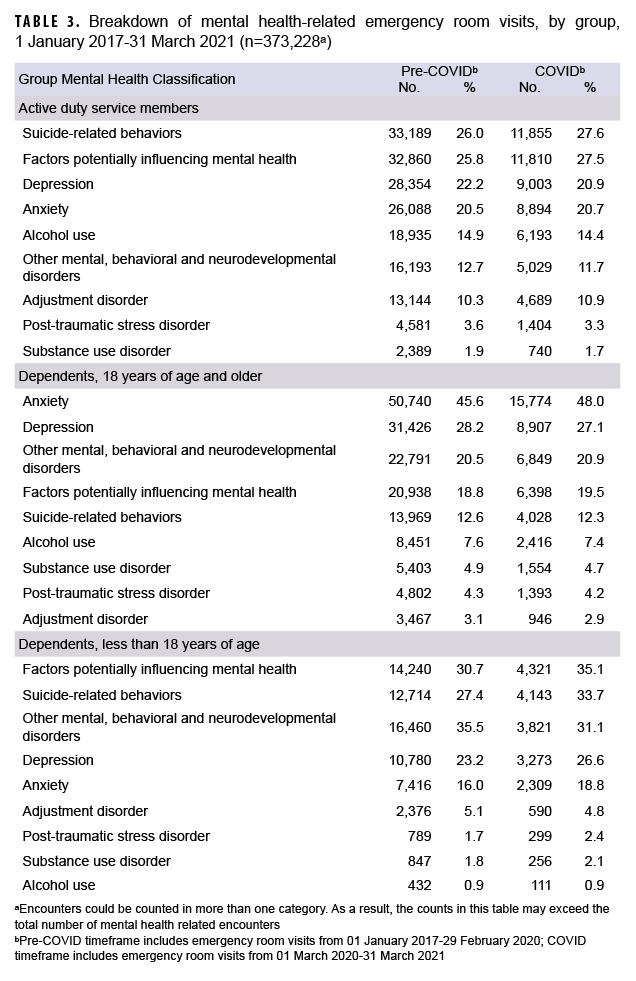

Consistent for both time periods, the most common conditions cited for mental health-related ER visits among ADSMs were suicide-related behaviors, for factors potentially influencing mental health (lifestyle-related problems [64%]; counseling and medical advice, not elsewhere classified [19%]; and problems related to primary support group [4%]; data not shown), and depression. Anxiety and depression were cited in over half the mental health-related ER visits among dependents 18 years of age and older, with an increase in anxiety-related visits during the pandemic. Among dependents under 18 years of age, factors potentially influencing mental health (counseling/medical advice, not elsewhere classified [70%]; problems related to primary support group [6%]; and problems related to upbringing [5%]; data not shown), suicide-related behaviors, and other mental, behavioral and neurodevelopmental disorders (behavioral/emotional disorders [52%]; pervasive/specific developmental disorders [10%]; mental disorders due to known physiological conditions [6%]; data not shown) were associated with 83% of the ER visits related to mental health. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the proportion of visits related to mental health behaviors and suicide-related behaviors among dependents under 18 years of age increased by 14.3% and 23.0%, respectively (Table 3).

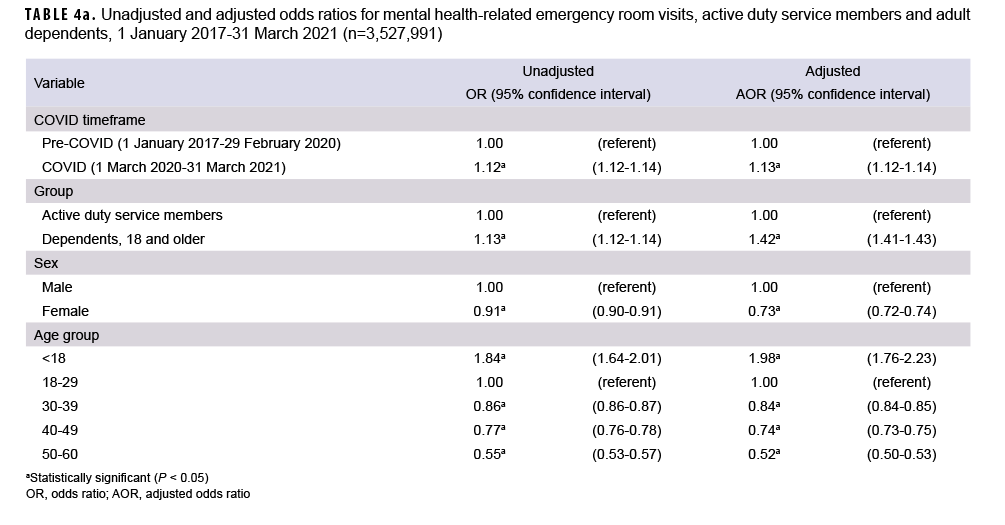

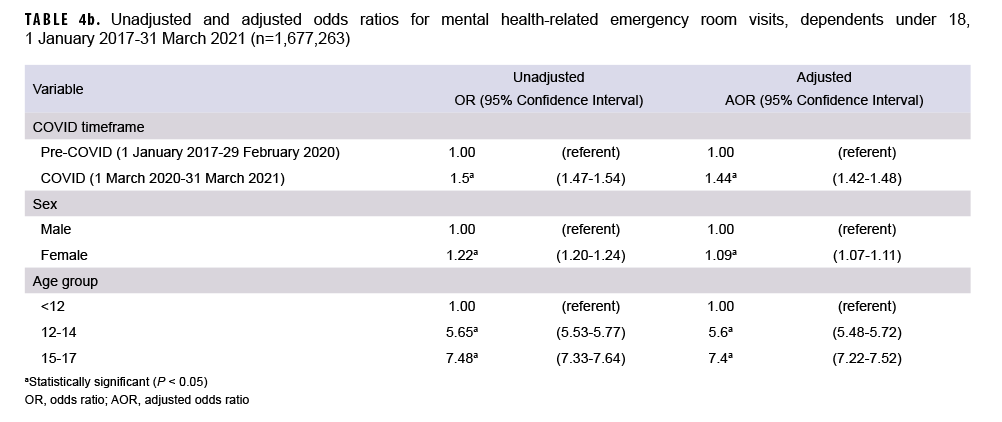

For both service member/adult dependents and dependents under age 18, the odds of mental health-related ER visits being higher during COVID compared to the pre-COVID period were statistically significant (P<0.05). Among the combined group of ADSMs and dependents 18 and older, the COVID-19 timeframe’s higher odds for mental health-related ER visits remained significant after adjustment for age, sex, and beneficiary group (OR: 1.13, 95%CI: 1.12, 1.14) (Table 4a). The same was true for dependents under 18 years, after adjustment for age and sex (OR: 1.44, 95%CI: 1.42, 1.48) (Table 4b).

EDITORIAL COMMENT

These findings build on previously published studies that show increases in self-reported mental health symptoms during the pandemic.5-7 Observed increases in the proportions of ER visits related to mental health among ADSMs and their dependents in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic were modest yet significant. During COVID-19, ERs restricted access to only those most in need of urgent care, including those seeking mental health care, thus impacting the proportions in this analysis. Although monthly average ER visits decreased by 30%, the proportion of visits related to mental health experienced a relative increase of 24.3%. It is indeterminable if this difference was due to increased mental health concerns caused by the pandemic or to the altered access to care within ERs and associated triage efforts; however, results in this study point to changes in the mental health of the population during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Similar to previous findings, this study showed that ER visits during COVID-19 were 1.44 times more likely to relate to mental health among dependents under 18 years of age compared to the pre-COVID-19 period, after adjustments for age and sex.5,8 During the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, this younger cohort experienced a relative increase in the proportion of mental health-related ER visits citing depression (+14.7%), anxiety (+17.5%), and most notably, suicide-related behaviors (+23%), reproducing a similar trend noted by other research in the immediate aftermath of the pandemic.5

The main limitations of this study come from its cross-sectional nature. The same individual could not be followed over time, limiting the ability to draw causal conclusions. Due to the nature of these data, one cannot definitively identify the primary reason for a visit. Additionally, the codes within the “factors potentially influencing mental health” grouping are typically used to indicate the presence of an issue, short of a diagnosable condition, but variation in coding practices could have influenced the outcomes of interest.14 Data from facilities transferring to MHS GENESIS during the study timeframe were excluded from this analysis, due to known data gaps and lack of data validation, which might have biased results. Lastly, due to the large sample size being analyzed in this study, even small differences will be statistically significant. Consequently, it is important to delineate between results that are statistically significant and clinically significant.

Poor mental health of ADSMs and their families negatively affects force readiness. The COVID-19 pandemic illustrates the importance of considering all types of external stressors when supporting service members and their families.

Author Affiliations

General Dynamics Information Technology, Inc. (Mr. Dinkeloo); Navy and Marine Corps Public Health Center (Mr. Dinkeloo, Ms. Luse).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the contributions of Ernest Williams, Emmyrose Khan, and Nancy Blowe of the Navy and Marine Corps Public Health Center for input and guidance on statistical analysis and editing.

Disclaimers

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, nor the U.S. Government. The authors are military Service Members or employees of the U.S. Government. This work was prepared as part of their official duties. Title 17, U.S.C., §105 provides that copyright protection under this title is not available for any work of the U.S. Government. Title 17, U.S.C., §101 defines a U.S. Government work as a work prepared by a military Service Member or employee of the U.S. Government as part of that person’s official duties.

REFERENCES

- Hossain MM, Tasnim S, Sultana A, et al. Epidemiology of mental health problems in COVID-19: a review. F1000Res. 2020;9:636.

- Singh S, Roy D, Sinha K, Parveen S, Sharma G, Joshi G. Impact of COVID-19 and lockdown on mental health of children and adolescents: a narrative review with recommendations. Psychiatry Res. 2020;293:113429.

- Lancet Public Health. COVID-19: From a PHEIC to a public mental health crisis? Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(8):e414.4.

- Clark L, Fan M, Stahlman S. Surveillance of mental and behavioral health care utilization and use of telehealth, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 1 January 2019–30 September 2020. MSMR. 2021;28(8):22-27.

- Czeisler ME, Lane RI, Petrosky E, et al. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic—-United States, June 24-30, 2020. MMWR. 2020;69(32):1049-1057.

- Newby JM, O'Moore K, Tang S, Christensen H, Faasse K. Acute mental health responses during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia. PLoS One. 2020;15(7):e0236562.

- Pierce M, Hope H, Ford T, et al. Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(10):883-892.

- Ridout KK, Alavi M, Ridout SJ, et al. Emergency department encounters among youth with suicidal thoughts or behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(12):1319-1328.

- Update: mental health disorders and mental health problems, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2016-2020. MSMR. 2021;28(8):2-9.

- Defense Health Agency. DOD Health of the Force 2019. https://health.mil/Reference-Center/Reports/2020/11/24/DoD-Health-of-the-Force-2019. Accessed November 15, 2022.

- Stahlman S, Oetting AA. Mental health disorders and mental health problems, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2007-2016. MSMR. 2018;25(3):2-11.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Social Determinants of Health. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/icd/social-determinants-of-health.pdf. Accessed November 15, 2022.

- Association Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th Edition 2013.

- Truong HP, Luke AA, Hammond G, Wadhera RK, Reidhead M, Joynt Maddox KE. Utilization of social determinants of health ICD-10 z-codes among hospitalized patients in the United States, 2016-2017. Med Care. 2020;58(12):1037-1043.