Abstract

Prior studies have found a higher risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes due to COVID-19 infection; however, recent literature documents few adverse impacts to younger and otherwise healthy populations, but with limited information about military members. The study population comprised active component service women with a singleton delivery between 2021 and 2023. Adverse pregnancy outcomes were evaluated by COVID-19 infection and vaccination history, as well as by demographics and pre-existing comorbidities. During the surveillance period, 39,355 active component U.S. service women had a singleton delivery. After controlling for potential confounders in the adjusted logistic regression analysis, COVID-19 infection during pregnancy was associated with eclampsia (OR 2.18, p<0.05) and antepartum hemorrhage (OR 1.11, p<0.05), and COVID-19 infection prior to the start of pregnancy was associated with antepartum hemorrhage (OR 1.18, p<0.05). In comparison, after adjustment, COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy and prior to start of pregnancy was not associated with increased odds of any adverse pregnancy outcome in active component service women. COVID-19 vaccines are recommended for pregnant women by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and, previously, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

What are the new findings?

This analysis found no significant difference in adverse pregnancy outcomes among those who received a COVID-19 vaccine prior to delivery compared to women who did not, between 2021 and 2023. COVID-19 infection prior to start of pregnancy was associated with antepartum hemorrhage whereas COVID-19 infection during pregnancy was associated with eclampsia and antepartum hemorrhage.

What is the impact on readiness and force health protection?

The findings from this analysis suggest there is a benefit to vaccinating pregnant active component service women against COVID-19. There was no increased risk of these adverse pregnancy outcomes associated with receipt of a COVID-19 vaccine in this study population. In contrast, COVID-19 infection may be associated with increased occurrence of some adverse pregnancy events.

Background

COVID-19 infection during pregnancy has been associated with an increased risk of certain pregnancy complications such as pre-eclampsia and pre-term birth.1,2 Severity of COVID infection may also play a role, as more severe infections have been more strongly linked to pre-term premature rupture of membranes.3 The increased risk for stillbirth and pre-eclampsia could be due to inflammatory changes affecting the placenta, and the need for intensive care associated with severe disease could result in the increased rates of pre-term delivery.4

In 1 cohort study of electronic health care records in southeastern Texas, COVID-19 infection before and during pregnancy were associated with spontaneous abortion.5 Other studies, however, found no association between COVID-19 infection and risk of miscarriage.6 One matched retrospective cohort study of over 170,000 pregnancies found a 12% higher risk for gestational diabetes following COVID-19 infection during the first 21 weeks of pregnancy.7 This association could be due to inflammation increasing insulin resistance, damage to the pancreas, or shared risk factors for more severe COVID-19 infection.8,9 In contrast, studies of COVID-19 vaccination in pregnant women have not revealed increased risk of adverse maternal or neonatal outcomes including stillbirth, pre-term birth, hypertensive disorders, congenital malformations, or other conditions due to vaccination.10-12 In fact, some studies have indicated that COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy can reduce risk of stillbirth and pre-term birth.13,14 Consequently, during the pandemic the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended that all pregnant patients remain up-to-date with COVID-19 vaccines before and during pregnancy.15 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists also recommends that patients receive an updated COVID-19 vaccine or ‘booster’ at any point during pregnancy.16

Healthy women infected with COVID-19 during pregnancy primarily experience mild illness with limited or no significant adverse effects on the mother or neonate.4,17 Women in active duty military service must maintain physical fitness standards and represent a relatively young and healthy population; as a result, it would be expected that COVID-19 infection would not increase risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes, in most situations. The objective of this study was to evaluate associations between COVID-19 infection during pregnancy and certain adverse pregnancy outcomes in active component U.S. service women who had a delivery between 2021 and 2023, with a review of any change in this association for women who received a COVID-19 vaccine during or prior to their pregnancy start dates. This study focused on adverse conditions that would be coded in the maternal record, since data from neonatal medical records were not available.

Methods

Methods

Study population

This cross-sectional study used inpatient and outpatient direct and Click to closePurchased CareThe TRICARE Health Program is often referred to as purchased care. It is the services we “purchase” through the managed care support contracts.purchased care medical encounter records from the Defense Medical Surveillance System (DMSS). The study population included U.S. active component service women who had a singleton delivery, either live or still birth outcome, from January 1, 2021 through December 31, 2023. International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes were used to determine singleton live (Z370) or still births (Z371). The first birth event in this surveillance period was used if a woman had multiple delivery events during the period. Deliveries were included if a woman was on active component duty during the 280 days preceding the delivery date. The pregnancy start date was calculated as the date 280 days prior to the delivery event.

Outcomes

The outcomes for this study were specific adverse pregnancy events diagnosed within 280 days preceding the first singleton delivery event during the surveillance period. Outcomes included antepartum hemorrhage or threatened abortion (ICD-10: O20* or O46*), gestational diabetes (O24.4*), eclampsia (O15*), pre-eclampsia (O14*), pre-term labor or delivery (O60*), premature rupture of membranes (O42*), and stillbirth (Z37.1). For the gestational diabetes analysis, individuals were excluded from the study population if they had an inpatient or outpatient diagnosis of ICD-10: E10* (type 1 diabetes), E11* (type 2 diabetes), O24.4* (gestational diabetes), or O24.9* (unspecified diabetes) prior to the start of pregnancy.

Exposures of interest

The exposures of interest in this study were COVID-19 infection before or during pregnancy and COVID-19 vaccination before or during pregnancy. The Armed Forces Health Surveillance Division (AFHSD) maintains a master list of COVID-19 cases for active component service members. These COVID-19 cases were identified from reports of positive antigen, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and confirmed or probable tests that were entered into the Disease Reporting System internet (DRSi) prior to January 2023, and Electronic Surveillance System for the Early Notification of Community-based Epidemics (ESSENSE) positive antigen and PCR tests that occurred on or after January 2023.

Anyone with multiple positive COVID-19 tests or reports was counted as 1 infection if both tests were within a 90-day period, consistent with guidelines from the CDC.18 A woman was categorized as having a COVID-19 infection during pregnancy if there was a documented COVID-19 infection within 280 days prior to her delivery event, and categorized as having COVID-19 infection prior to pregnancy if it occurred more than 280 days prior to the delivery event.

DMSS immunization data were utilized to determine COVID-19 vaccination status. A single dose of any of the following CVX codes met criteria for receiving a COVID-19 vaccination: 207, 208, 212, 221, 217, 211, 229, 300, 309, 312, 313, 510, 511, 502, or 210.19 These data are provided to DMSS from the MHS Information Platform (MIP) Immunizations Tracking System. DMSS only receives immunizations data for U.S. military service members.

Covariates

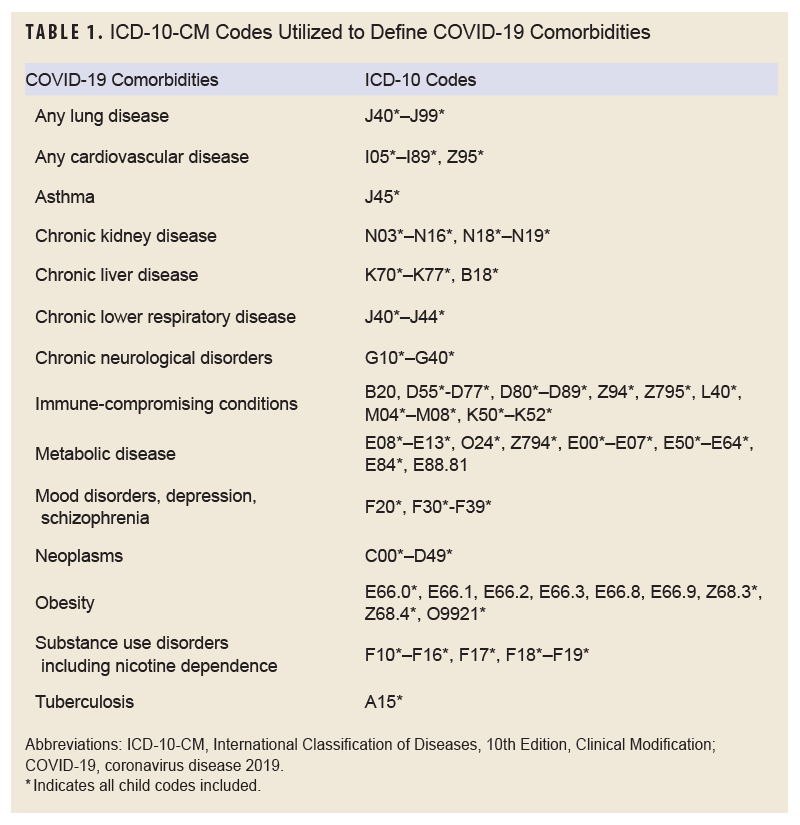

Covariates for this study included age, race and ethnicity, service branch, number of prior deliveries, and comorbidities diagnosed prior to the start of the pregnancy. Electronic Periodic Health Assessment (PHA) data were reviewed to determine a service member’s self-reported smoking status within the 2 years prior the start of the associated pregnancy. Smoking was used as a covariate for its documented link to adverse maternal health outcomes.13 Other lifestyle factors were not readily available from the PHA and thus were not included for covariate analysis. Pre-existing comorbidities were identified by having a diagnosis of that condition in any diagnostic position of an inpatient or outpatient encounter within 2 years prior to the delivery date (Table 1). For assessment of the number of prior deliveries, 1 delivery was counted every 280 days (ICD-10 codes Z37*, O80, O82). All births were classified as vaginal or cesarian section (ICD-10: O82* or inpatient procedure codes 10D00; outpatient CPT codes 59510, 59515, 59514, 00850, 00857, 01961, 01963, 01968, 01969; diagnostic group codes 370, 371). Age, race and ethnicity, and service branch were assigned based on demographic data for the member at the time of the delivery event.

Statistical analysis

Pearson chi-square tests were used to assess the relationship between exposures of interest and covariates with the adverse pregnancy outcomes. Adjusted logistic regression models were used to further explore the associations between the exposures of interest and study outcomes that were significant in the crude (unadjusted) analysis. These models adjusted for COVID-19 infection prior to the start of pregnancy, COVID-19 infection during pregnancy, COVID-19 vaccination prior to the start of pregnancy, COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy, age, race and ethnicity, number of prior deliveries, and any previously diagnosed comorbidity. Covariates were selected for inclusion in the adjusted models based on being exposures of interest or significant potential confounders.

Results

A total of 39,355 active component service women experienced a singleton delivery between January 1, 2021 and December 31, 2023 (Table 2). Of those service women, 29,927 (76.0%) had vaginal deliveries, and 9,428 (24.0%) had cesarean sections. A total of 5,190 (13.2%) of these women had a documented COVID-19 infection during pregnancy, and 6,491 (16.5%) had a COVID-19 infection prior to pregnancy. Among women with an infection prior to the start of pregnancy, the first infection was a median of 233 days (IQR 110-402 days) prior.

A total of 9,236 (23.5%) active component service women received at least 1 COVID-19 vaccine dose during pregnancy, and 22,056 (56.0%) received a dose prior to start of pregnancy. There were 27,685 (70.3%) women who received a vaccine dose on or prior to the delivery event, less than the sum of women (n=31,292) who received at least 1 dose during and prior to start of pregnancy, because some women received a dose both prior to and during pregnancy. The percentage of women who received at least 1 dose by their delivery date increased each calendar year: 30% for deliveries in 2021, 91% for deliveries in 2022, 99% for deliveries in 2023.

Most service women had no documented prior deliveries (69.1%). Most service women were ages 20-34 years (86.9%), while non-Hispanic White service women comprised the largest racial and ethnic group (41.6%). Obesity (11.7%), immune-compromising conditions (11.2%), and metabolic disease (11.1%) were the most commonly diagnosed comorbidities within the 2 years prior to pregnancy.

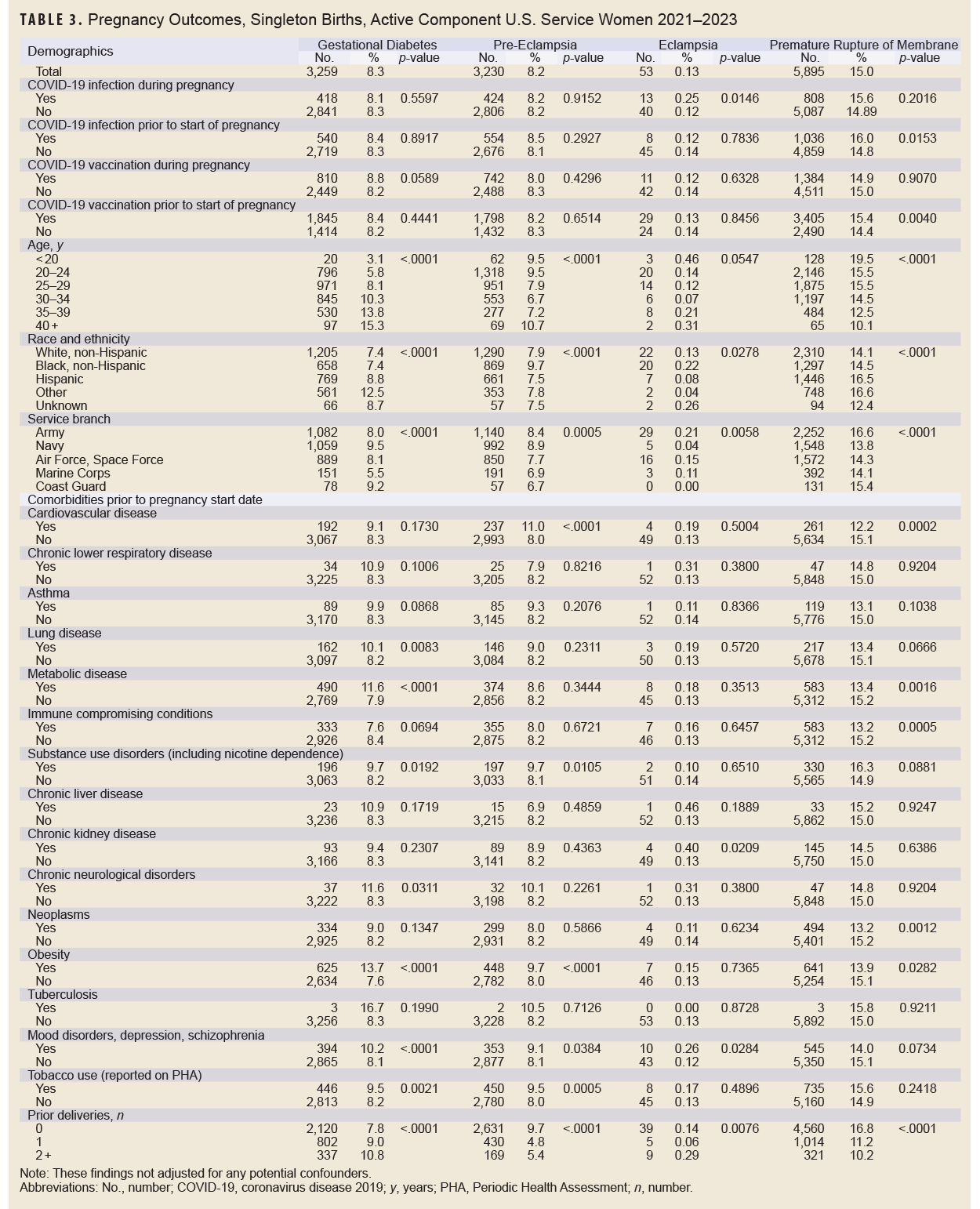

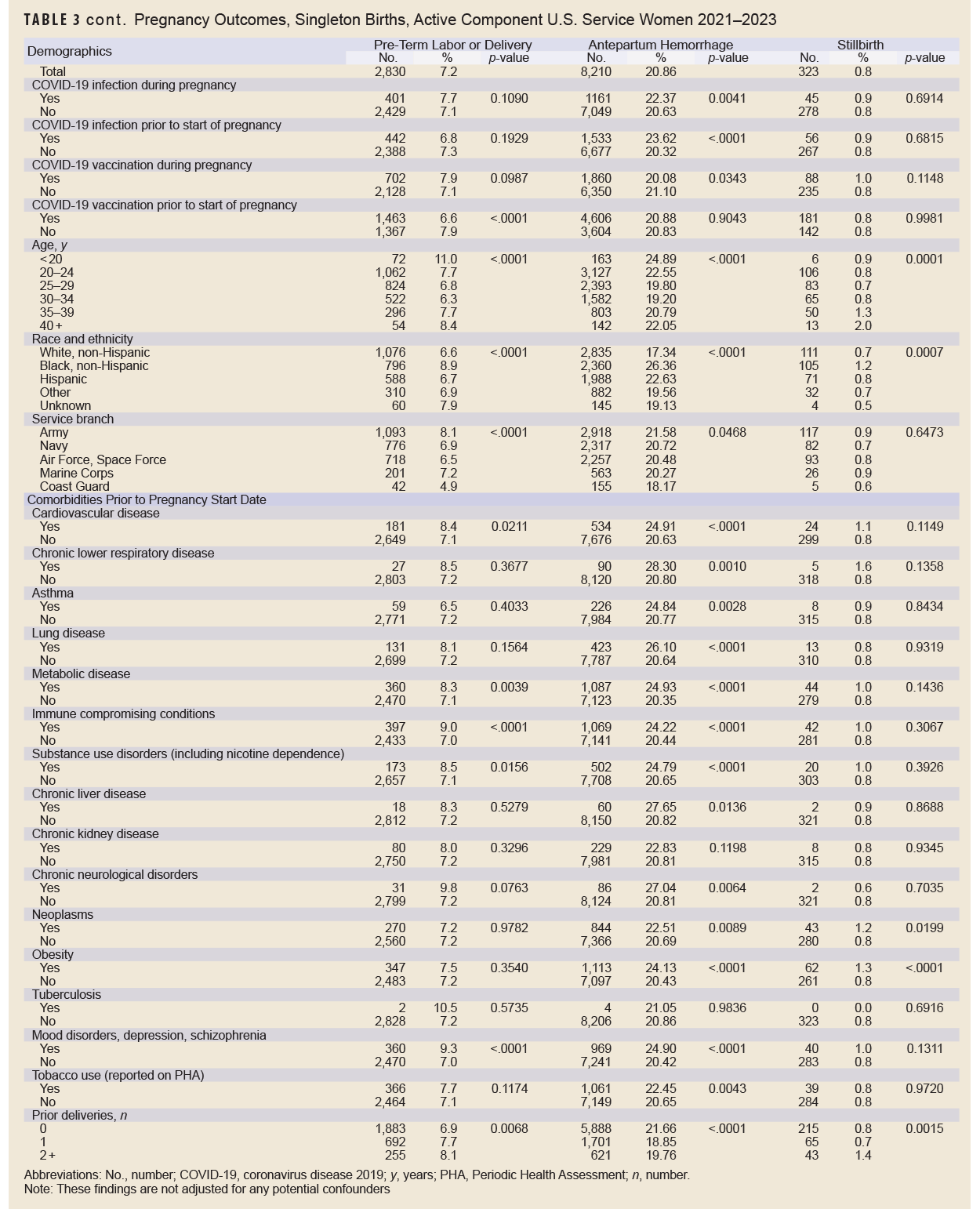

Without adjusting for any potential confounders, antepartum hemorrhage was the most common adverse pregnancy outcome (20.9%), followed by premature rupture of membranes (15.0%), gestational diabetes (8.3%), pre-eclampsia (8.2%), pre-term labor or delivery (7.2%), stillbirth (0.8%), and eclampsia (0.1%) (Table 3). Black, non-Hispanic service women had the highest percentage of pre-eclampsia, eclampsia, antepartum hemorrhage, and stillbirth. Generally, prevalence of adverse pregnancy outcomes tended to be higher among service women with certain pre-existing comorbidities. For example, pre-eclampsia and antepartum hemorrhage were more prevalent among service women with cardiovascular disease. Pre-eclampsia, gestational diabetes, antepartum hemorrhage, and stillbirth were more common among service women with obesity.

In many cases, there was not a significant (p<0.05) difference in prevalence of adverse pregnancy outcomes in service women according to COVID-19 infection or vaccination status, with a few notable exceptions (Table 3). COVID-19 infection during pregnancy was associated with a higher percentage of eclampsia and antepartum hemorrhage; COVID-19 infection prior to start of pregnancy was associated with a higher percentage of antepartum hemorrhage and premature rupture of members; COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy was associated with lower percentage of antepartum hemorrhage; and COVID-19 vaccination prior to the start of pregnancy was associated with a higher percentage of premature rupture of membranes and a lower percentage of pre-term labor or delivery.

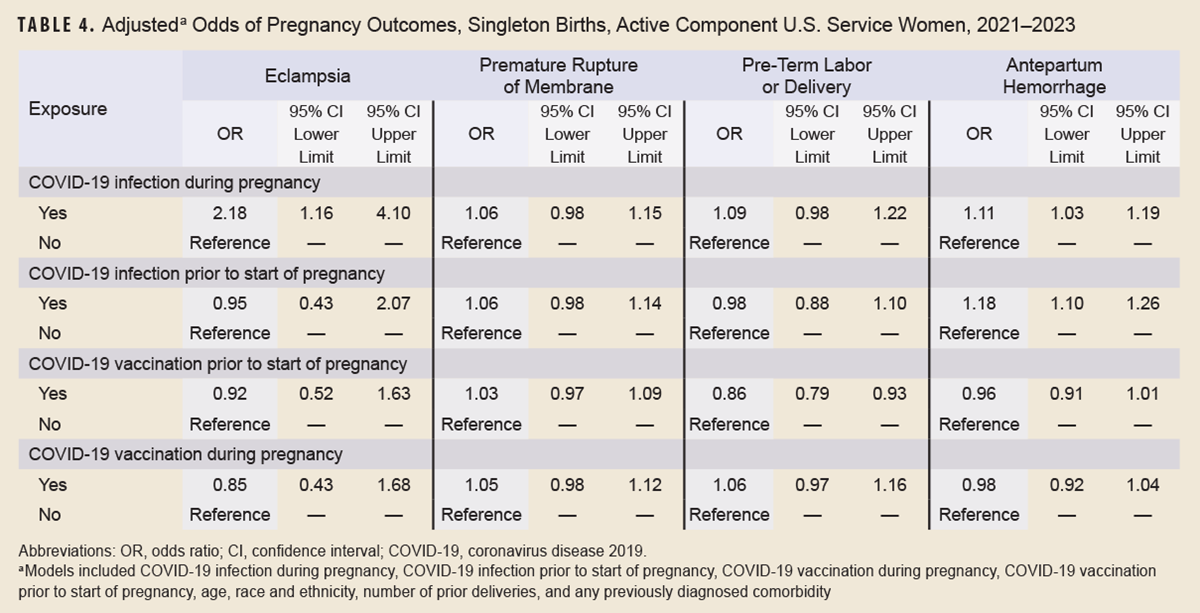

After controlling for potential confounders in the adjusted logistic regression analysis, COVID-19 infection during pregnancy remained significantly and positively associated with eclampsia (OR 2.18, p<0.05) and antepartum hemorrhage (OR 1.11, p<0.05), and COVID-19 infection prior to start of pregnancy remained significantly and positively associated with antepartum hemorrhage (OR 1.18, p<0.05) (Table 4). After adjustment, COVID-19 vaccination prior to start of pregnancy was no longer associated with premature rupture of membranes. COVID-19 vaccination prior to start of pregnancy was, however, inversely associated (OR 0.86, p<0.05) with pre-term labor or delivery.

Discussion

This study found increased odds of eclampsia and antepartum hemorrhage, which includes threatened abortion or any bleeding during pregnancy, among active component service women with a documented COVID-19 infection during pregnancy. In contrast, COVID-19 vaccination during or prior to start of a pregnancy was not associated with increased odds of any adverse pregnancy outcome, after adjustment for potentially confounding factors. It is important to note that these findings cannot be generalized to the U.S. population, nor to earlier periods during the COVID-19 pandemic when vaccines were not widely available, and pre-existing immunity was low or non-existent. It is possible that by the period of analysis for this study, members of the study population may have already had COVID-19 illness and thereby developed natural immunity, which could not be identified. It is estimated that by June 2021 74% of active component service members had been exposed to COVID-19, either by prior infection or vaccination.20

A mandate issued by the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) on August 24, 2021 required service members to receive a COVID-19 vaccination by December 31, 2021. That requirement was rescinded in January 2023, however, by Section 525 of the National Defense Authorization Act.21,22 This study concurs with prior research that reveals that receipt of a COVID-19 vaccine prior to or during pregnancy was not associated with any change in adverse pregnancy outcomes, including antepartum hemorrhage and stillbirth.10-12 The results of this study are also consistent with a recently published article from the DOD’s Birth and Infant Health Registry, which found that COVID-19 vaccination was not associated with increased risk for pre-term birth, small size for gestational age, low birth weight, or neonatal intensive care unit admission among active duty service women who gave birth in 2021.23

The highest percentage of adverse pregnancy outcomes occurred in Black, non-Hispanic service women, consistent with other research that reveals elevated levels of adverse pregnancy outcomes in this population.24 This study population differs from most other studies, however, because military service women have access to robust medical care and surveillance during their pregnancies, which eliminates access to care as a potential confounder for the association between race and pregnancy outcome. Consequently, the findings in this study support the possibility of other factors besides access to care that contribute to the increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes in non-Hispanic Black service women.25

Consistent with prior studies, preexisting comorbidities were associated with different types of adverse pregnancy outcomes.26-28 Further studies should be conducted to validate the finding of potential associations between COVID-19 infection and eclampsia and antepartum hemorrhage, since it was not possible in this study to determine whether COVID-19 infection was the cause of those adverse outcomes.

Some limitations to this study are important to note. First, in this cross-sectional study design, temporality between COVID-19 infection or COVID-19 vaccination that occurred during pregnancy cannot be inferred with these adverse pregnancy outcomes. It is possible that some adverse pregnancy outcomes occurred prior to the documented COVID-19 infection. COVID-19 infection and vaccination prior to the start of pregnancy does infer temporality, however, which adds to the robustness of these findings.

Selection bias could have occurred in this study because pregnancies that ended in abortion, spontaneous or otherwise, were not included. If COVID-19 infection and adverse pregnancy outcomes are associated with spontaneous abortions, this would result in a negative bias, or an attenuation of the true association between COVID-19 infection and an adverse pregnancy outcome.

It is also unlikely that all COVID-19 infections during pregnancy were identified in this study, as at-home COVID test kits were rapidly deployed during the surveillance period. In addition, service women had the ability to test outside of the military’s medical system, resulting possible in misclassification for some categorized as without COVID-19 infection when they were potentially infected during their pregnancy. Similarly, women with no or mild COVID-19 symptoms may not have realized they were infected and, therefore, would not have tested.

This study considered women with any dose of any COVID-19 vaccine as vaccinated. As such, a misclassification bias is possible if these women were not fully vaccinated. Remaining up-to-date with COVID-19 vaccines was believed to provide the most benefit in the prevention of both severe adverse pregnancy outcomes and COVID-19 disease.15

Lastly, it should be noted that 52% (n=4,298) of the cases of antepartum hemorrhage had a diagnosis of O20.0 for “threatened abortion,” which can also be used to code bleeding during pregnancy. This coding could result in an over-estimate of antepartum hemorrhage cases, since bleeding during pregnancy is a more common and less severe outcome. Similarly, premature rupture of membranes may be over-estimated because 52% (n=3,079) of those cases had a diagnosis of O42.02, “Full-term premature rupture of membranes, onset of labor within 24 hours of rupture,” which suggests that, for half of these cases, the rupture occurred at or after 37 completed weeks of gestation.

This study provides insight on adverse pregnancy outcomes among pregnant U.S. active component service women. These findings suggest that COVID-19 vaccination is not associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes in this population. Future studies should review the prevalence of these outcomes in this population, refine and validate any associations with COVID-19 infection, along with the various levels of vaccination on adverse neonatal outcomes, and further investigate outcomes for pregnant active component service women of racial and ethnic minorities, to determine the reasons for these differences, given their equal access to no-cost medical care.

Author Affiliations

Lackland Trainee Health Squadron, Joint Base San Antonio-Lackland, TX: Maj Ching; Armed Forces Health Surveillance Division, Public Health Directorate, Defense Health Agency, Silver Spring, MD: Ms. Murray, Dr. Wells, Dr. Stahlman

Disclaimer

The content of this presentation is the sole responsibility of its authors and does not reflect the views nor policies of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Inc., U.S. Department of Defense, or the departments of the Army, Navy, or Air Force. Mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

References

- Boettcher LB, Metz TD. Maternal and neonatal outcomes following SARS-CoV-2 infection. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2023;28(1):101428. doi:10.1016/j.siny.2023.101428

- Xu K, Sun W, Yang S, Liu T, Hou N. The impact of COVID-19 infections on pregnancy outcomes in women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2024;24(1):562. doi:10.1186/s12884-024-06767-7

- Palma A, Niño-Huertas A, Bendezu-Quispe G, Herrera-Añazco P. Association between the degree of severity of COVID-19 infection during pregnancy and preterm premature rupture of membranes in a level III hospital in Peru. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica. 2023;40(4):432-440. doi:10.17843/rpmesp.2023.404.12957

- Male V. SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2022;22(5):277-282. doi:10.1038/s41577-022-00703-6

- Sandoval MN, Klawans MR, Bach MA, et al. COVID-19 infection history as a risk factor for early pregnancy loss: results from the electronic health record-based Southeast Texas COVID and Pregnancy Cohort Study. BMC Med. 2025;23(1):274. doi:10.1186/s12916-025-04094-y

- van Baar JAC, Kostova EB, Allotey J, et al. COVID-19 in pregnant women: a systematic review and meta-analysis on the risk and prevalence of pregnancy loss. Hum Reprod Update. 2024;30(2):133-152. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmad030

- Rincón-Guevara O, Wallace B, Kompaniyets L, Barrett CE, Bull-Otterson L. Association between SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy and gestational diabetes: a claims-based cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2024;79(6):1386-1393. doi:10.1093/cid/ciae416

- Govender N, Khaliq OP, Moodley J, Naicker T. Insulin resistance in COVID-19 and diabetes. Prim Care Diabetes. 2021;15(4):629-634. doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2021.04.004

- Wu CT, Lidsky PV, Xiao Y, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infects human pancreatic β cells and elicits β cell impairment. Cell Metab. 2021;33(8):1565-1576.e5. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2021.05.013

- Prasad S, Kalafat E, Blakeway H, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness and perinatal outcomes of COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):2414. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-30052-w

- Ciapponi A, Berrueta M, Argento FJ, et al. Safety and effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines during pregnancy: a living systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Saf. 2024;47(10):991-1010. doi:10.1007/s40264-024-01458-w

- Buekens P, Berrueta M, Ciapponi A, et al. Safe in pregnancy: a global living systematic review and meta-analysis of COVID-19 vaccines in pregnancy. Vaccine. 2024;42(7):1414-1416. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2024.02.012

- Hui L, Marzan MB, Rolnik DL, et al. Reductions in stillbirths and preterm birth in COVID-19-vaccinated women: a multicenter cohort study of vaccination uptake and perinatal outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2023;228(5):585.e1-585.e16. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2022.10.040

- Zels G, Colpaert C, Leenaerts D, et al. COVID-19 vaccination protects infected pregnant women from developing SARS-CoV-2 placentitis and decreases the risk for stillbirth. Placenta. 2024;148:38-43. doi:10.1016/j.placenta.2024.01.015

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 Vaccination for Women Who Are Pregnant or Breastfeeding. U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services. Accessed Sep. 21, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/covid/vaccines/pregnant-or-breastfeeding.html

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Releases Updated Maternal Immunization Guidance for COVID-19, Influenza, and RSV. Accessed Sep. 21, 2025.

- Wang CL, Liu YY, Wu CH, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on pregnancy. Int J Med Sci. 2021;18(3):763-767. doi:10.7150/ijms.49923

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About Reinfection. U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services. Updated Jun. 14, 2024. Accessed Sep. 21, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/covid/about/reinfection.html

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. IIS: Current HL7 Standard Code Set CVX–Vaccines Administered. U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services. Updated Dec. 18, 2024. Accessed Jan. 30, 2025. https://www2a.cdc.gov/vaccines/iis/iisstandards/vaccines.asp?rpt=cvx

- Taylor KM, Ricks KM, Kuehnert PA, et al. Seroprevalence as an indicator of undercounting of COVID-19 cases in a large well-described cohort. AJPM Focus. 2023;2(4):100141. doi:10.1016/j.focus.2023.100141

- Secretary of Defense. Memorandum: Mandatory Coronavirus Disease 2019 Vaccination of Department of Defense Service Members. U.S. Dept. of Defense. Updated Aug. 24, 2021. Accessed Aug. 28, 2023. https://media.defense.gov/2021/aug/25/2002838826/-1/-1/0/memorandum-for-mandatory-coronavirus-disease-2019-vaccination-of-department-of-defense-service-members.pdf

- Secretary of Defense. Memorandum: Rescission of Coronavirus Disease 2019 Vaccination Requirements for Members of the Armed Forces. U.S. Dept. of Defense. Updated Jan. 10, 2023. Accessed Aug. 22, 2023. https://media.defense.gov/2023/jan/10/2003143118/-1/-1/1/secretary-of-defense-memo-on-rescission-of-coronavirus-disease-2019-vaccination-requirements-for-members-of-the-armed-forces.pdf

- Hall C, Lanning J, Romano CJ, et al. COVID-19 vaccine initiation in pregnancy and risk for adverse neonatal outcomes among United States military service members, January–December 2021. Vaccine. 2025;51:126894. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2025.126894

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pregnancy mortality surveillance system. U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services. Updated Mar. 23, 2023. Accessed Sep. 21, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/maternal-mortality/php/pregnancy-mortality-surveillance-data

- Hall C, Bukowinski AT, McGill AL, et al. Racial disparities in prenatal care utilization and infant small for gestational age among active duty US military women. Matern Child Health J. 2020;24(7):885-893. doi:10.1007/s10995-020-02941-3

- Ziert Y, Abou-Dakn M, Backes C, et al. Maternal and neonatal outcomes of pregnancies with COVID-19 after medically assisted reproduction: results from the prospective COVID-19-Related Obstetrical and Neonatal Outcome Study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;227(3):495.e1-495.e11. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2022.04.021

- Sayad B, Mohseni Afshar Z, Mansouri F, et al. Pregnancy, preeclampsia, and COVID-19: susceptibility and mechanisms: a review study. Int J Fertil Steril. 2022;16(2):64-69. doi:10.22074/ijfs.2022.539768.1194

- Smith ER, Oakley E, Grandner GW, et al. Clinical risk factors of adverse outcomes among women with COVID-19 in the pregnancy and postpartum period: a sequential, prospective meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2023;228(2):161-177. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2022.08.038