What Are the New Findings?

The 2018–2019 influenza season was longer than the preceding 2 seasons. Unlike most prior seasons, 2 strains were common. Influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 was the most common strain early in the season, but influenza A(H3N2) predominated later in the season. Total influenza vaccine effectiveness was low during this season in part because the A(H3N2) strain was antigenically drifted from the vaccine strain.

What Is the Impact on Readiness and Force Health Protection?

Surveillance data about influenza disease inform the planning and strategy for efforts to reduce the future impact of influenza on the health and medical readiness of the Armed Forces. The data and findings in this report reinforce the importance of the use of up-to-date multivalent influenza vaccines that protect against several different specific virus strains that may become common in the coming influenza season.

Abstract

The Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch conducts weekly surveillance of influenza activity among Department of Defense (DOD) populations each influenza season. This report provides a summary of the data from the 2018–2019 influenza season. Ambulatory data for influenza-like illnesses (ILIs), influenza hospitalization data, and lab data for influenza-confirmed cases were used for the surveillance. The 2018–2019 season differed from past seasons in that it was much longer, had a later peak, and the predominant strain of influenza changed from influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 at the beginning of the season to influenza A(H3N2) in the middle of the season. Non-service member beneficiaries accounted for the majority of ILI-related encounters and hospitalizations. However, there were still 149 influenza-related hospitalizations among service members during the 2018–2019 season. Continued weekly surveillance of influenza among DOD populations is crucial to track increases in activity each season and the potential emergence of new and/or severe influenza subtypes.

Background

Influenza infects an estimated 8% of the U.S. population annually, with children and the elderly at highest risk.1 Service members may also be at a higher risk for exposure to influenza because of increased crowding and mixing in the recruit setting and duty assignments abroad where influenza subtypes may differ.2 Each influenza season is different because of antigenic drift in the circulating influenza subtypes, the degree of match between vaccine subtypes and circulating subtypes, and vaccine coverage of the population. As such, it is important to conduct annual surveillance of each influenza season to identify the onset and patterns of activity, emergence of drifted or shifted subtypes, and severity of the season.

The Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch of the Defense Health Agency utilizes electronic sources of ambulatory medical encounters, hospitalizations, and laboratory data to conduct annual influenza surveillance among all Department of Defense (DOD) beneficiaries across the world. Weekly reports are generated to provide near real-time influenza surveillance data for each of the DOD Combatant Commands. This report provides a summary of DOD influenza surveillance data for the 2018–2019 influenza season.

Methods

Medical encounter and demographic data from the Defense Medical Surveillance System (DMSS) and Health Level 7 (HL7)-formatted laboratory data from the Navy and Marine Corps Public Health Center (NMCPHC) were used for this analysis. The HL7-formatted laboratory data are non standardized, so NMCPHC applies an algorithm to the data to identify influenza tests and standardize results. The surveillance period for the 2018–2019 influenza season was 30 Sept. 2018 through 1 June 2019 (influenza weeks 40 through 22). Data from the 2016–2017 and 2017–2018 influenza seasons are also presented for comparison. The surveillance population included all individuals who were Military Health System (MHS) beneficiaries (i.e., active and reserve/guard component service members, retired service members, family members and other dependents of service members and retirees, and other authorized government employees and family members) who accessed care through either a military medical facility/provider or a civilian facility/provider (if paid for by the MHS). However, medical data from military treatment facilities (MTFs) that were using MHS GENESIS at the time of this surveillance (Naval Hospital Oak Harbor, Naval Hospital Bremerton, Air Force Medical Services Fairchild, and Madigan Army Medical Center) are not captured in the DMSS data. Therefore, medical encounter and laboratory data from these MTFs are not included in the analysis. For the analysis, populations were grouped as service members or other beneficiaries.

Outpatient medical encounters were classified as an influenza-like illness (ILI) encounter if they had an ILI diagnosis code (International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision [ICD-10] codes B97.89, H66.9, H66.90, H66.91, H66.92, H66.93, J00, J01.9, J01.90, J06.9, J09, J09.X, J09.X1, J09.X2, J09.X3, J09.X9, J10, J10.0, J10.00, J10.01, J10.08, J10.1, J10.2, J10.8, J10.81, J10.82, J10.83, J10.89, J11, J11.0, J11.00, J11.08, J11.1, J11.2, J11.8, J11.81, J11.82, J11.83, J11.89, J12.89, J12.9, J18, J18.1, J18.8, J18.9, J20.9, J40, R05, R50.9) in any diagnostic position. The percentage of all outpatient encounters that were classified as ILI encounters was calculated for each week for each study population. Baseline ILI activity for the season was defined as the mean percentage of all outpatient encounters during non influenza weeks (weeks 22–39) over the prior 3 years.

Hospitalized influenza cases were defined as having a hospitalization with a diagnosis of influenza (ICD-10: J09, J10, J11) in any diagnostic position. The number of hospitalized influenza cases each week for each study population was calculated. For other beneficiaries, counts of influenza hospitalizations by age group (0–4, 5–9, 10–17, 18–35, 36–49, 50–64, 65+) were calculated.

Laboratory-confirmed influenza cases were defined as having a positive polymerase chain reaction, viral culture, or rapid influenza assay result. Laboratory-confirmed influenza cases were stratified by influenza types/subtypes (influenza A (not subtyped), influenza A(H1N1)pdm09, influenza A(H3N2), influenza A and B coinfection, and influenza B. The total number of laboratory-confirmed influenza cases stratified by type/subtype and the percentage of all influenza laboratory tests performed that had positive test results were calculated for each week of the influenza season for service members and for other beneficiaries separately.

Results

Virus surveillance

Among all beneficiaries, there were 149,254 respiratory specimens tested for influenza during the 2018–2019 influenza season (data not shown). Of those, 30,464 (20.4%) were positive for influenza. Service members had a lower percentage of specimens testing positive for influenza (16.7%) compared to other beneficiaries (21.8%). Among all populations, influenza A (any subtype) predominated during this season, with 28,454 (93.4%) of all positive specimens testing positive for influenza A. The distribution of subtypes among influenza A positive specimens was 73.3% influenza A (not subtyped), 12.6% A(H3N2), and 7.5% A(H1N1)pdm09. The remaining specimens were positive for influenza B (1,805; 5.9%) or an influenza A/B coinfection (205; 0.7%). The distribution of subtypes was similar between service members and other beneficiaries (data not shown).

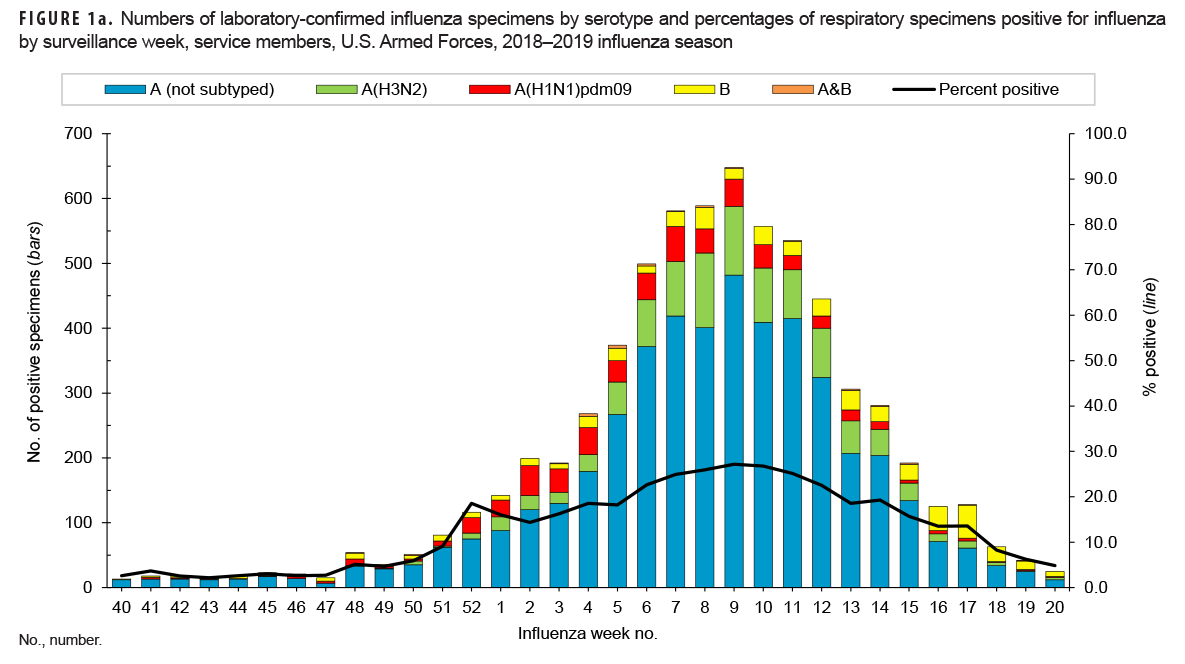

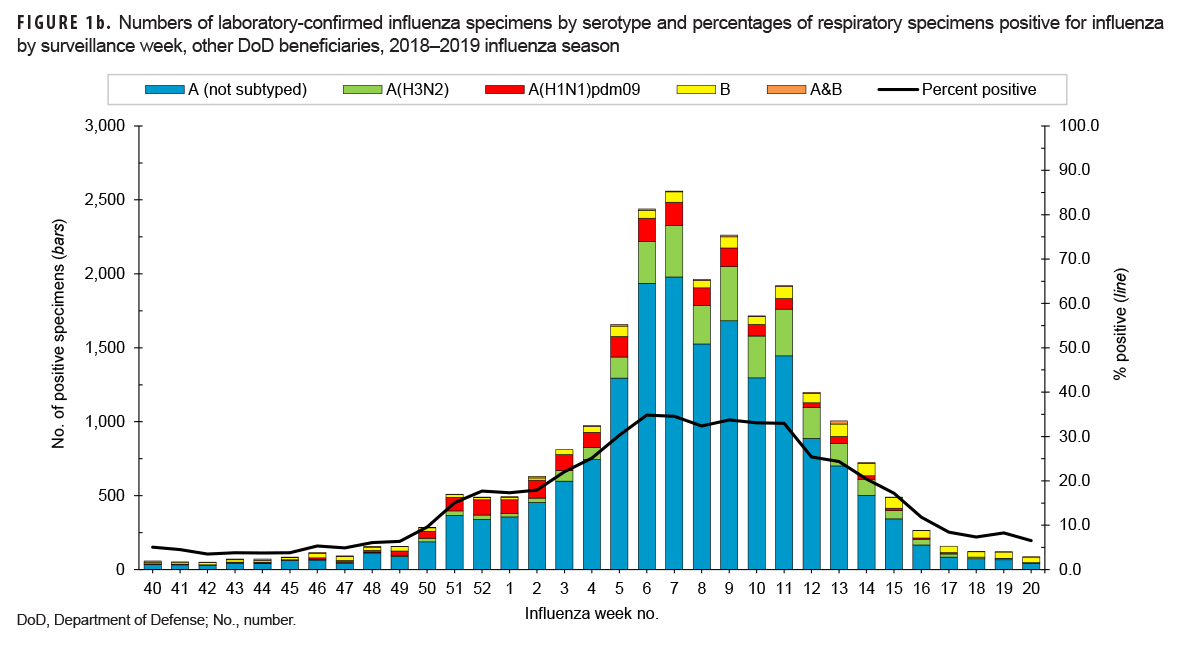

The distribution of influenza serotypes and the percentage of specimens positive for influenza by week are presented in Figures 1a and 1b for service members and other beneficiaries, respectively. Among subtyped influenza A specimens, A(H1N1) pdm09 predominated early in the season, but A(H3N2) was predominant after week 3. The highest numbers of positive specimens and the highest percentages of positives occurred during week 9 for service members and weeks 6 and 7 for other beneficiaries. These results indicate peak influenza activity for the season during the month of Feb. 2019.

Outpatient encounter ILI surveillance

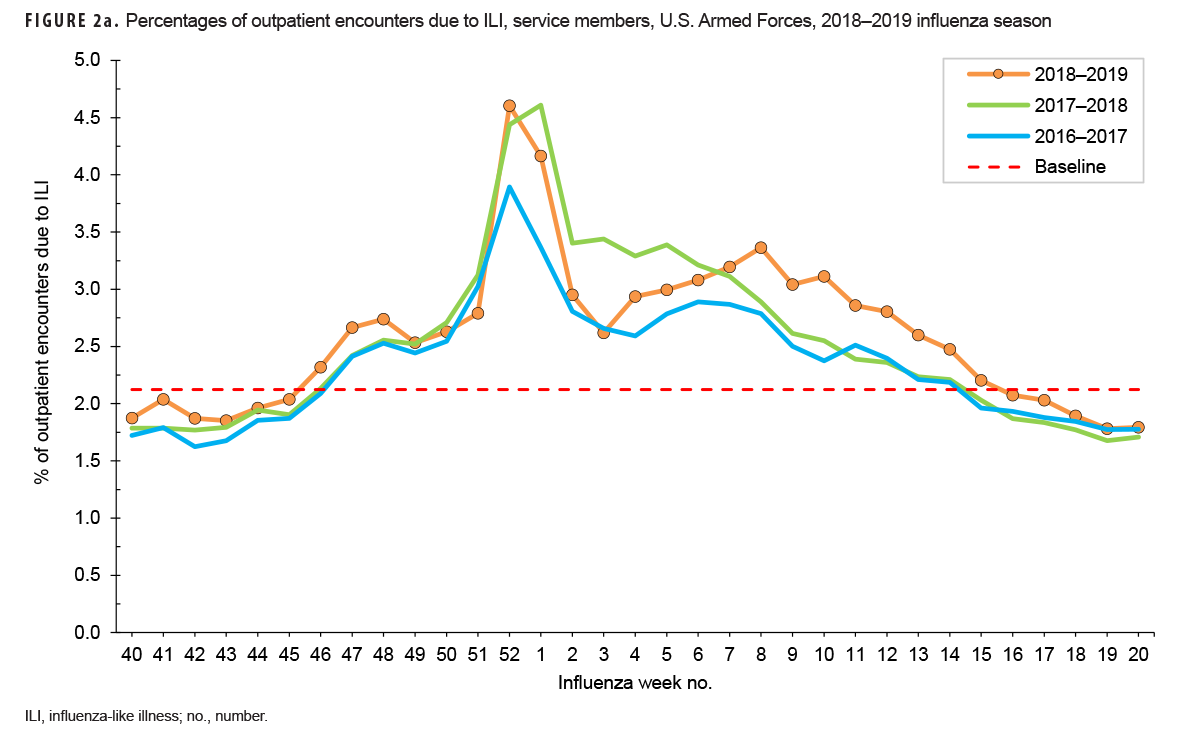

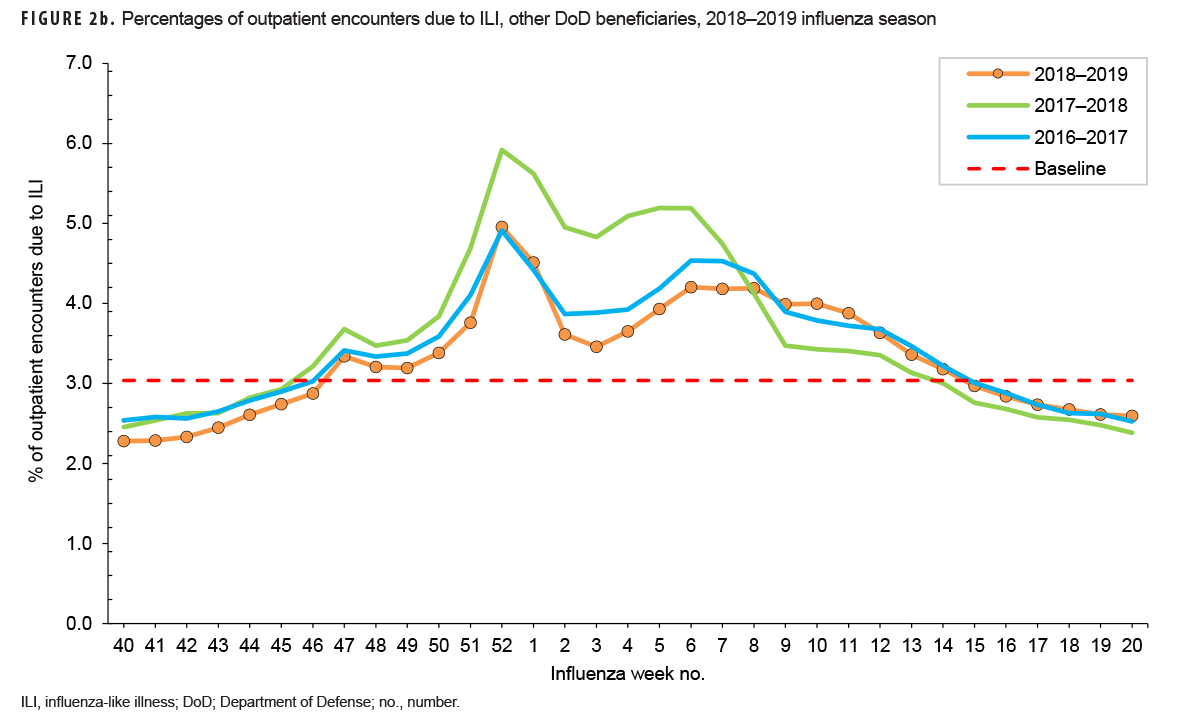

During the 2018–2019 season, the weekly percentages of outpatient encounters due to an ILI for service members were above baseline (2.1%) for 22 weeks (weeks 46–15) (Figure 2a). A similar pattern was seen among other beneficiaries, for whom the percentages were above baseline (3.4%) for 20 weeks (weeks 47–14) (Figure 2b). This pattern is similar to the percentage of outpatient encounters due to ILI during the prior 2 influenza seasons.

Earlier in the 2018–2019 season, between weeks 40–52, the trend and magnitude of the percentages of encounters due to ILI were also similar to those of the past 2 seasons (Figures 2a and 2b). All seasons had peaks during weeks 52 and 1. This timing coincides with the end-of-year holiday period. Rather than a true peak in ILI activity though, this peak was being driven by a differential decrease in the total number of medical encounters and ILI encounters during that time. Specifically, for the 2018–2019 season, the total number of outpatient medical encounters decreased 58% from week 51 to week 52; however, ILI encounters decreased only 36% between those 2 weeks. Therefore, this peak in ILI percentage is considered an artifact of the overall decline in total outpatient encounters and is not reflected in the peak influenza weeks for the season. After week 1, the 2018–2019 season ILI percentages began to diverge from the prior 2 seasons. Among service members, the percentage of encounters due to ILI had a later peak (week 8) than the prior 2 seasons (weeks 2 and 3), but the magnitude of the 2018–2019 peak was similar to that of the 2017–2018 peak (Figure 2a). Among other beneficiaries, the trend was similar to the 2 prior seasons, with peak activity occurring during week 6 (2017–2018: week 5; 2016–2017: week 6), and the magnitude was similar to the 2016–2017 season (Figure 2b).

Influenza-related hospitalizations

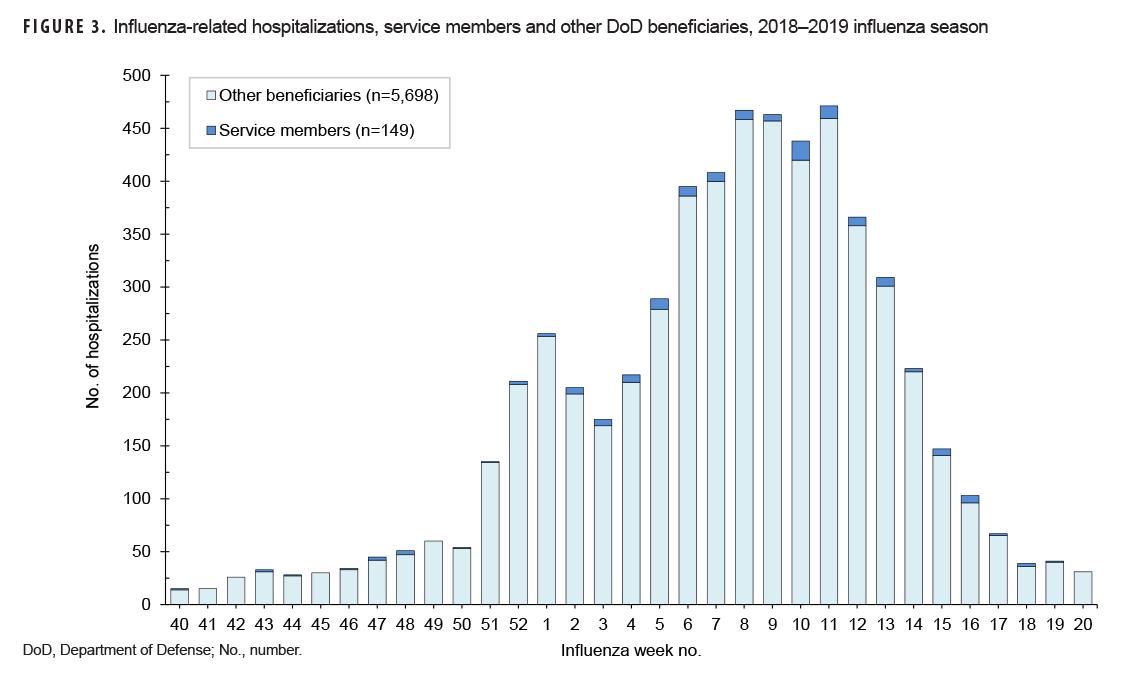

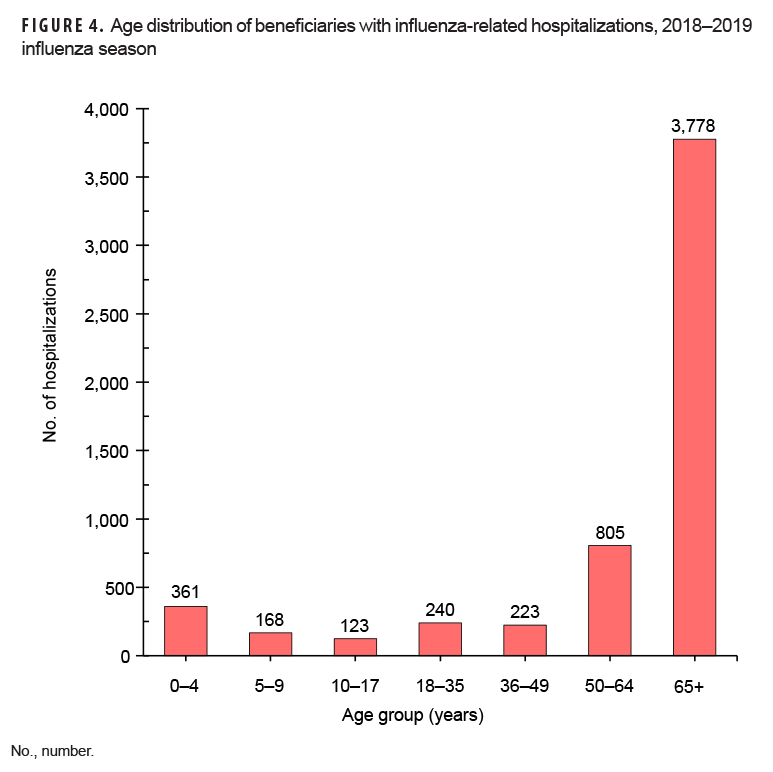

Of the total 5,847 influenza-related hospitalizations during the 2018–2019 season, 149 occurred among service members (Figure 3). The majority of hospitalizations occurred among other beneficiaries (n=5,698; 97.5%). Hospitalizations peaked overall during week 11 (n=471), but service member hospitalizations peaked during week 10 (n=18) (Figure 3). Among other beneficiaries, the majority of influenza-related hospitalizations occurred among those 65 years of age or older (n=3,778; 66.3%) (Figure 4).

Editorial Comment

The 2018–2019 influenza season among service members and other DOD beneficiaries was a longer season with a later peak compared to the prior 2 seasons. The season also differed from prior seasons in that the beginning of the season was predominated by influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 while influenza A(H3N2) predominated after week 3; most seasons have just 1 influenza A subtype predominating. As expected, the influenza season among DOD service members and beneficiaries was similar to the season among the general U.S. population.3 Although the DOD influenza surveillance data include information from around the world, the majority of encounter and laboratory data came from the U.S. and to a lesser extent Europe, which also had an influenza season similar to that in the U.S.4 As with the general U.S. population, the elderly (> 64 years of age) accounted for the majority of influenza hospitalizations among other beneficiaries. The elderly population accounted for 66% of all other beneficiary hospitalizations for the season compared to 47% among the general U.S. population.3

A seasonal influenza vaccine is still the best way to protect against influenza. Service members are required to receive a seasonal influenza vaccine annually. During the 2018–2019 season, DOD policy set a goal of 90% of service members vaccinated by 15 Jan. 2019.5 Although vaccination rates of service members were very high, influenza cases still occurred among this population during the 2018–2019 season. Cases of influenza among service members may be attributable to infections occurring before receipt of the influenza vaccine, within the 14 days following vaccination when the vaccine may not provide complete protection, or after vaccination because the vaccine is less than 100% effective. During the 2018–2019 season, vaccine effectiveness among the general U.S. population was particularly low because of the emergence of a drifted A/H3N2 (clade 3C.3a) circulating virus that differed from the vaccine strain.6 Although the influenza vaccine is not 100% effective at preventing influenza infection, a recent study showed that vaccination also decreased the risk of hospitalization and admission to the intensive care unit and decreased severity of illness.7 Continued vaccination of service members and other DOD beneficiaries is crucial to combat influenza infections and lessen disease severity. This season also demonstrated the importance of annual influenza surveillance, as the seasons differ from year to year.

References

- Tokars JI, Olsen SJ, Reed C. Seasonal incidence of symptomatic influenza in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(10):1511–1518.

- Sanchez JL, Cooper MJ. Influenza in the US military: an overview. J Infec Dis Treat. 2016;2(1).

- Xu X, Blanton L, Elal AIA, et al. Update: Influenza activity in the United States during the 2018–19 season and composition of the 2019–20 influenza vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(24):544–551.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Weekly influenza update, week 20, May 2019. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/weekly-influenza-update-week-20-may-2019. Accessed 28 Jan. 2020.

- Department of Defense Assistant Secretary of Defense. Memorandum: Guidance for the 2018–2019 Annual Influenza Immunization Program. 05 July 2018.

- Flannery B, Kondor RJG, Chung JR, et al. Spread of antigenically drifted influenza A(H3N2) viruses and vaccine effectiveness in the United States during the 2018–2019 season. J Infect Dis. 2020;221(1):8–15.

- Thompson MG, Pierse N, Sue Huang Q, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in preventing influenza-associated intensive care admissions and attenuating severe disease among adults in New Zealand 2012–2015. Vaccine. 2018;36(39):5916–5925.