Background

Aggression is defined as behavior intended to inflict physical or psychological harm, and can be verbal or physical.1,2 Aggressive behavior is common among active component service members, with approximately half reporting that they engaged in aggressive behavior within the past month.3,4 Further studies show that rates of aggression are increasing.3,4 Although well-regulated aggression (e.g., toward an enemy; in a response to an attack) may be necessary for combat engagement, uncontrolled aggression (e.g., domestic violence, physical fights with other service members) can have significant negative psychological, social, and occupational ramifications. Aggression is associated with poorer occupational productivity and retention,5 and increased risk of legal problems.6–8 Research also suggests that aggression may be a form of non-suicidal self-injury,9 and that it may predict increased suicide risk;10 approximately 43% of service members who attempted suicide reported they acted to "stop feeling angry, frustrated, or enraged."11 Additional research on aggression is needed to identify service members at high risk of these behaviors in order facilitate prevention, mitigation, assessment, and intervention.

Another area that warrants further examination is the relationship between aggression and mental health among service members. Approximately 14% pf service members have a diagnosed psychological condition,12 with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), major depressive disorder (MDD), and anxiety disorders being among the most prevalent.12-13 The relationship between PTSD and aggression is well-established; service members with PTSD report higher levels of aggression compared to those without PTSD.14-16

Recent evidence suggests that service members with symptoms of depression and anxiety are more likely to report anger problems.17–18 However, only 1 study has examined associations between depression or anxiety and aggression among service members, finding that aggression was associated with a self-reported history of depression and anxiety "problems" among soldiers.14 Given the gap in knowledge, additional studies are needed. This study examines associations between 3 mental health conditions—probable MDD, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), and PTSD—and aggression among active component sailors.

Methods

In Jan. 2021, all crew members from a docked Naval aircraft carrier were invited to complete an anonymous questionnaire that assessed demographic characteristics, aggressive behaviors, and symptoms of mental health disorders. The questionnaire was completed on computer tablets provided by the research team and was administered as part of a larger, mixed-methods study designed to assess stress and health among shipboard sailors. Participation was voluntary and all crew members were eligible to participate. Study procedures were approved by the Naval Health Research Center Institutional Review Board.

Aggressive behavior was assessed using 4 items adapted from previous research; however, the version of the scale employed in the current study has not been previously validated.19–20 Participants reported how often during the past month they yelled or shouted at someone, kicked or smashed something, threatened someone with physical violence, or got into a fight or harmed someone. Responses ranged from 0 (never) to 4 (5 or more times). Respondents who had engaged in each behavior 1 or more times in the past month were classified as positive for that behavior. Items were also examined as a summed scale score, which assesses frequency of aggressive behaviors over the past month (range 0–16; Cronbach's alpha=0.68).

Clinically validated screening tools were used to assess mental health symptoms; each tool has been widely used in military populations.21–23 Responses to the Patient Health Questionnaire-924 were used to assess depression symptoms over the previous 2 weeks. Per clinical guidelines, participants were categorized as having probable MDD if they answered "more than half the days" or "nearly every day" on 5 or more of the items, including either item 1 (diminished pleasure or interest) or item 2 (depressed mood) or if they endorsed item 9 [suicidal ideation]).25

Responses to the 7-item GAD-7 scale were used to assess anxiety symptoms over the previous 2 weeks; participants with summed scale scores >10 were categorized as having probable GAD.26

Post-traumatic stress symptoms were assessed using the abbreviated 8-item PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5).27 Participants were categorized as having probable PTSD if they had a summed scale score of >19 and if they reported prior experience of a Criterion A trauma (i.e., exposed to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence).27

Descriptive statistics were computed for all variables. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and chi-square tests of association were conducted to examine the relationship between participant characteristics, probable mental health disorders, and aggressive behaviors. To control risk of Type I error, all statistical tests were conducted using Bonferroni adjustments. All analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics, version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

Results

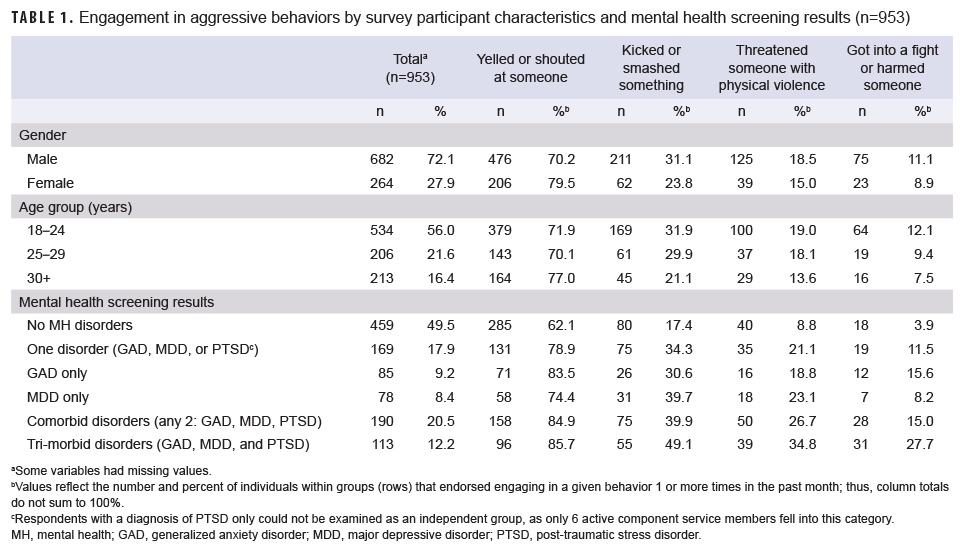

Nine-hundred fifty-three sailors (72.1% male) completed the survey (Table 1); approximately 30% of the crew participated in the study. Over three-quarters (76.4%) of participants reported engaging in at least 1 aggressive behavior in the past month, with less extreme forms of aggression being most common (data not shown). Yelling/shouting was more common among women (X2=8.2, p<.005), whereas kicking/smashing something was more common among men (X2=4.8, p<.05) (data not shown). Gender differences in the other aggressive behaviors were not statistically significant.

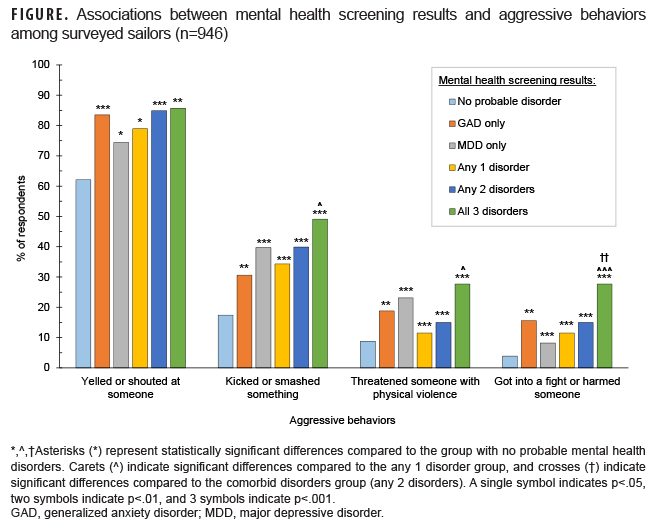

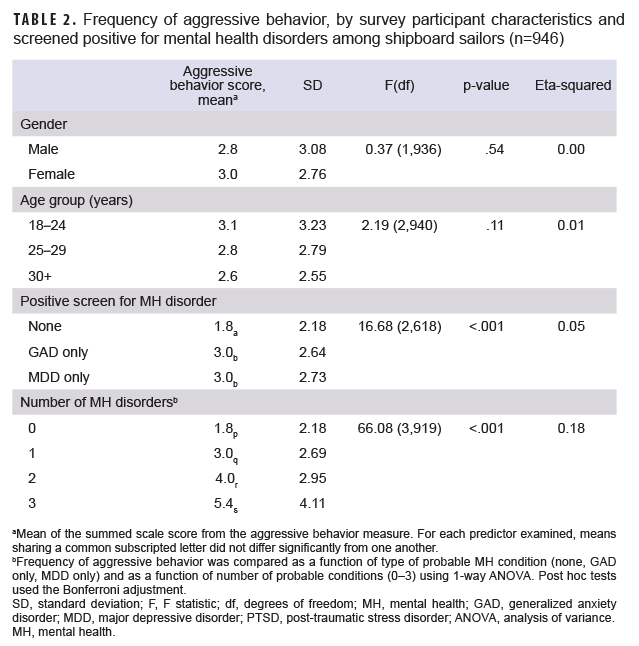

Approximately half of participants (50.5%) screened positive for at least 1 mental health disorder (Table 1). Overall frequency of aggressive behavior increased with increasing number of positive screens for mental health disorders. More specifically, sailors who screened positive for MDD or GAD (i.e., probable MDD/GAD) were more likely to engage in each of the 4 aggressive behaviors and reported greater frequency of aggressive behaviors overall (as measured by the summed scale score) when compared to individuals who screened negative (Tables 1, 2; Figure). Similarly, individuals with more than one positive screen for mental health disorder comorbidities reported more frequent aggressive behaviors than those with 1 or no probable mental health disorder diagnoses. Finally, those with probable MDD, GAD, and PTSD were more likely to get in a fight or harm someone, and had the highest frequency of aggressive acts, when compared to any other group (Table 2). The small number of participants with singular PTSD symptoms (n=6) precluded comparisons between PTSD and the other singular conditions.

Editorial Comment

This study documents associations between aggressive behaviors, demographic characteristics, and mental health conditions. In the current sample, female sailors reported initiating more verbal aggression whereas male sailors reported initiating more physical aggression. These findings are in line with prior research on gender differences in aggression among civilians.28–29 Individuals with probable MDD or GAD reported more frequent physical and verbal aggression than those without probable diagnoses and frequency of aggression rose with the number of probable mental health disorder diagnoses.

These findings may have clinical implications. Although aggression has previously been associated with PTSD, the current results indicate that military providers should regularly assess verbal and physical aggression among individuals with other mental health conditions as well, and in both male and female service members. Providers should also be aware that risk of aggression increases in the presence of comorbid mental health conditions. Clinically, this implies increased importance of assessing aggression among patients with comorbid mental health conditions and of incorporating elements to address aggression in treatment of patients with many types of common mental health disorders.

Although this study provides new information regarding aggression among service members, it is limited by a lack of prospective data, use of a non-validated aggression measure, lack of specificity regarding the target of their aggression, and a higher than expected rate of screening positive for mental health disorders (potentially confounded by the effects of the coronavirus disease 2019 [COVID-19] pandemic), preventing the examination of aggression among sailors with probable PTSD alone. Nonetheless, this research can guide improvements in mental health care provider training, as well as prevention, assessment, and intervention efforts.

Author affiliations: Leidos, Naval Health Research Center, San Diego, CA (Dr. Glassman, Ms. Englert, Dr. Harrison); Health and Behavioral Sciences Department, Naval Health Research Center, San Diego, CA (Dr. Glassman, Ms. Englert, Dr. Harrison, Dr. Thomsen); School of Public Health, Institute for Behavioral and Community Health, San Diego State University, San Diego, CA (Dr. Schmied).

Disclaimer: Several of the authors are military service members or employees of the U.S. Government. This work was prepared as part of their official duties. Title 17, U.S.C. §105 provides that copyright protection under this title is not available for any work of the U.S. Government. Title 17, U.S.C. §101 defines a U.S. Government work as work prepared by a military service member or employee of the U.S. Government as part of that person's official duties.

Project support: This project was supported by the Defense Health Agency under work unit no. N1809. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, nor the U.S. Government. The study protocol was approved by the Naval Health Research Center Institutional Review Board in compliance with all applicable Federal regulations governing the protection of human subjects. Research data were derived from an approved Naval Health Research Center Institutional Review Board protocol, number NHRC.2018.0003.

References

- Allen JJ, Anderson CA. Aggression and violence: Definitions and distinctions. In Sturmey S (Ed.). The Wiley Handbook of Violence and Aggression. Vol. 1, Part I. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons, 2017.

- Novaco RW. Cognitive–behavioral factors and anger in the occurrence of aggression and violence. In Sturmey S (Ed.). The Wiley Handbook of Violence and Aggression. Vol. 1, Part III. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons, 2017.

- Meadows SO, Engel CC, Collins RL, et al. 2015 Department of Defense Health Related Behaviors Survey (HRBS). Rand Health Q. 2018;8(2):5.

- Meadows SO, Engel CC, Collins RL, et al. 2018 Department of Defense Health Related Behaviors Survey (HRBS): Results for the Active Component. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2021. Accessed 18 May 2021. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR4222.html

- Booth J, Mann S. The experience of workplace anger. Leadersh Organ Dev J. 2005;26(4):250–262.

- Piquero NL, Piquero AR, Craig JM, Clipper SJ. Assessing research on workplace violence, 2000–2012. Aggress Violent Behav. 2013;18(3):383–394.

- Lawrence E, Bradbury TN. Physical aggression and marital dysfunction: A longitudinal analysis. J Fam Psychol. 2001;15(1):135–154.

- Heyman RE, Neidig PH. A comparison of spousal aggression prevalence rates in US Army and civilian representative samples. J Consult Clinical Psychol. 1999;67(2):239–242.

- Kimbrel NA, Thomas SP, Hicks TA, et al. Wall/object punching: An important but under-recognized form of nonsuicidal self-injury. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2017;48(5):501–511.

- Start AR, Allard Y, Adler A, Toblin R. Predicting suicide ideation in the military: The independent role of aggression. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2018;49(2):444–454.

- Bryan CJ, Rudd MD, Wertenberger E. Reasons for suicide attempts in a clinical sample of active duty soldiers. J Affect Disord. 2013;144(1–2):148–152.

- Mental Health Disorder Prevalence and Incidence among Active Duty Service Members, 2005–2017. Psychological Health Center of Excellence. Accessed 18 May 2021. https://www.pdhealth.mil/research-analytics/psychological-health-numbers/mental-health-disorder-prevalence-and-incidence

- Crum-Cianflone NF, Powell TM, LeardMann CA, Russell DW, Boyko EJ. Mental health and comorbidities in U.S. military members. Mil Med. 2016;181(6):537–545.

- Gallaway MS, Fink DS, Millikan AM, Bell MR. Factors associated with physical aggression among US Army soldiers. Aggress Behav. 2012;38(5):357–367.

- Ramchand R, Rudavsky R, Grant S, Tanielian T, Jaycox L. Prevalence of, risk factors for, and consequences of posttraumatic stress disorder and other mental health problems in military populations deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(5).

- Wilk JE, Quartana PJ, Clarke-Walper K, Kok BC, Riviere LA. Aggression in US soldiers post-deployment: Associations with combat exposure and PTSD and the moderating role of trait anger. Aggress Behav. 2015;41(6):556–565.

- Adler AB, LeardMann C, Roenfeldt KA, Jacobson IG, Forbes D, Team MCS. Magnitude of problematic anger and its predictors in the Millennium Cohort. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1–11.

- Novaco RW, Swanson RD, Gonzalez OI, Gahm GA, Reger MD. Anger and postcombat mental health: Validation of a brief anger measure with U.S. Soldiers postdeployed from Iraq and Afghanistan. Psychol Assess. 2012;24(3):661–675.

- McAnany J, Schmied E, Booth-Kewley S, Beckerley SE, Taylor MK. US Naval Unit Behavioral Health Needs Assessment Survey, Overview of Survey Items and Measures. San Diego, CA: Naval Health Research Center, 2014.

- Orpinas P, Frankowski R. The Aggression scale. Journal Early Adolesc. 2001;21(1):50–67.

- Resick PA, Wachen JS, Dondanville KA, et al. Variable-length cognitive processing therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in active duty military: Outcomes and predictors. Behav Res Ther. 2021;141:103846.

- Holloway IW, Green D, Pickering C, et al. Mental health and health risk behaviors of active duty sexual minority and transgender service members in the United States military. LGBT Health. 2021;8(2):152–161.

- Price M, Legrand AC, Brier ZMF, Gratton J, Skalka C. The short‐term dynamics of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms during the acute posttrauma period. Depress Anxiety. 2019;37(4):313–320.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613.

- American Psychiatric Association. Section II: Depressive Disorders. In: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092.

- Price M, Szafranski DD, van Stolk-Cooke K, Gros DF. Investigation of abbreviated 4 and 8 item versions of the PTSD Checklist 5. Psychiatry Res. 2016;239:124–130.

- Björkqvist K. Gender differences in aggression. Curr Opin Psychol. 2018;19:39–42.

- Archer J. Sex differences in aggression in real-world settings: A meta-analytic review. Rev Gen Psychol. 2004;8(4):291–322.