Background

Reinfection with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), is believed to be uncommon. However, suspected cases of reinfection have been reported from multiple countries, and many of these cases have been associated with SARS-CoV-2 variants.1-3 As the spread of the variants increases, so may the risk of reinfection. Reinfection is defined here as persons who were infected once, recovered, and then later became infected again. Unfortunately, it is difficult to differentiate reinfection from 1) reactivation of the virus which persisted after the original infection (despite apparent clinical recovery), 2) persistence of non-viable viral debris, or 3) laboratory error or variation. In one large contact tracing study in Korea, for example, 285 patients were found to have persistent positive results for up to 12 weeks after initial infection, but the Korea Centers for Disease and Prevention (KCDC) found no evidence of transmissibility or ability to isolate replication-competent virus.4

It is important to know if a person is re-infected in order to understand the true burden of disease. In addition, public health interventions, including isolation, investigating unvaccinated contacts, and vaccination are required for each case. Although a history of prior infection has been associated with an 84% lower risk of infection,5 subsequent reinfections have been increasing.6,7 Letizia et al. reported the rate of new infections among those with positive antibodies, even in a rigidly controlled basic training environment, to be 1.1 cases per person-year.7 Furthermore, belief that previous infection with SARS-CoV-2 leads to immunity from reinfection may result in behaviors which increase the likelihood of transmission and infection, including hesitancy and delays in vaccination.8 For these reasons, it is important to understand the scope and impact of recurrent SARS-CoV-2 positive tests in military and civilian populations.

This report details a case series of service members with repeated positive tests for SARS-CoV-2 in a U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command installation. The current findings underscore the need for a standardized approach to identify and respond to suspected cases of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection, and highlight the challenges of using this information to guide effective Force Health Protection (FHP) and communication strategies among Department of Defense (DOD) personnel.

Clinical Presentations

SARS-CoV-2 positive cases were identified through public health surveillance activities within the Moncrief Army Community Hospital's Department of Preventive Medicine at Fort Jackson, SC. Suspected cases were tested using the Cepheid Xpert® Xpress SARS-CoV-2 test on the GeneXpert® System (Cepheid Inc., Lawrence Livermore National Labs, CA) and the BinaxNOW™ (Abbott Diagnostics Scarborough, Inc., Scarborough, ME) antigen card. Both are authorized for use under a Food and Drug Administration Emergency Use Authorization. The Xpert Xpress SARS-CoV-2 utilizes real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) testing for qualitative and quantitative detection of viral nucleic acid from patients suspected of infection with the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Approved for use as a qualitative diagnostic, this assay (run on the GeneXpert system) generates a report that includes result interpretation and the cycle threshold (Ct) value, (i.e., the number of cycles required in order for the signal to cross and exceed the background threshold). The Ct value is inversely proportional to the number of copies of the target nucleic acid (i.e., copy number) and the number of whole viral genomes in the actual sample. Earlier or lower Ct values suggest a higher viral load, while later or higher values suggest a lower viral load. The BinaxNOW™ antigen card is a lateral flow immunoassay, point-of-care test (POCT) used strictly for the qualitative detection of SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein antigen.

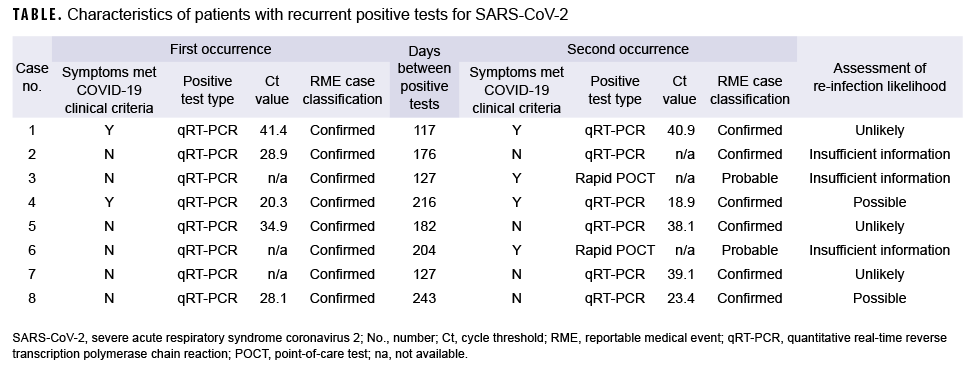

Eight service members with recurrent positive SARS-CoV-2 tests were identified at Fort Jackson, SC between July 2020 and March 2021 (Table). All were enlisted service members ranging in age from 18 to 31 years of age (mean=23.6 years) (data not shown). None of the 8 service members were identified as close contacts of one another. Six were male; 5 were originally identified as Army basic trainees; 6 had initially reported no symptoms, although 2 of the 6 later displayed symptoms upon reinfection; one had recently returned from an overseas location (data not shown). None had any SARS-CoV-2 tests performed (qRT-PCR or POCT) other than those listed (Table). The average number of days between 2 positive tests was 174 (range: 117–243 days). None had received any doses of COVID-19 vaccine by the time of the potential second infection. None of the patients were hospitalized at any time, and all recovered without any complications. Only one was employed in health care. Of note, all service members were isolated and had their contacts quarantined during both episodes.

All 8 of the service members met the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) case definition for confirmed or probable infection with both the first and the second positive test; 9 and, therefore all were reported as COVID-19 cases both times as per DOD reporting requirements.10 The confirmed cases all had a positive qRT-PCR, while the probable cases had symptoms, which met the clinical criteria, and a positive rapid test. The criteria for investigation of suspected reinfection from the CDC were used to assess the likelihood of COVID-19 reinfection.11 The factors which make reinfection more likely included: presence of symptoms, interval ≥ 90 days between positive tests, lower or earlier Ct values (i.e., less than 33), and presence of at least 1 negative test between occurrences. The CDC also requires that a respiratory sample from each infection episode be available for further investigation using genomic sequencing, but no such specimens were available for any of these service members. Many of the Ct values seen in these service members were high or late (i.e., weakly positive), suggesting that they are more likely to be false positives or persistent low-level positives from an earlier infection. Based on these criteria, 2 were considered to be possible reinfections, 3 were unlikely, and 3 had insufficient information to assess.

Editorial Comment

The risk of having a positive test for SARS-CoV-2 after prior infection has been estimated at 14.8%, but this includes both viral persistence as well as reinfections.12 Younger patients, such as the service members seen in this report, have been shown to be more likely to have recurrent positives, and they are the predominant group with delayed (>90 days) recurrent positives.13 However, in the absence of genome sequence data, it is difficult to determine if the cases are truly reinfections. In this study, 3 of the 8 patients identified were assessed as unlikely to have had a reinfection and 3 had insufficient information to assess reinfection. Complicating this assessment is the fact that there is no standardized or accepted definition of a SARS-CoV-2 reinfection, although several have been proposed.14,15 Another limitation of this study that should be taken into consideration when interpreting the results was the use of quantitative data from the GeneXpert, which was approved as a qualitative but not a quantitative test. Finally, rapid POCTs can vary in sensitivity and specificity based on viral load and patient presentation.

For these reasons, a more thorough investigation is recommended for future suspected cases of reinfection using the CDC investigation protocol.11 Specifically, viral culture and genomic sequencing of paired specimens (one from each episode) should be undertaken to confirm the presence of transmissible virus and to identify unique variants or infections.11,16 The CDC protocol states that investigations of reinfection should prioritize persons in whom SARS-CoV-2 RNA has been detected ≥ 90 days since first SARS-CoV-2 infection whether or not symptoms were present.11 Persons with COVID-19-like symptoms and detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA 45–89 days since first SARS-CoV-2 infection may also be investigated if they had a symptomatic second episode and no obvious alternate etiology for COVID-19-like symptoms or close contact with a person known to have laboratory-confirmed COVID-19.11 The investigation of both groups requires paired specimens and is only recommended for those with a cycle threshold (Ct) value <33 or if the Ct value is unavailable. Genomic testing can then provide evidence of whether the second positive test represents a true reinfection. Serial collection of respiratory specimens and serologic testing may also help to assess reinfection status.

The uncertainty in the reinfection status also has implications for surveillance data and public health response. If these are true cases of reinfection, then they should be counted as new incident cases. However, if they are false positives or persistent positives from the original infection, counting them will result in overestimates of the true disease burden. The reinfection status of most of these service members is doubtful or uncertain based on the criteria listed above, suggesting that service members should be counted only once as incident cases until more compelling evidence of true reinfection is presented. Additionally, the isolation of most of the service members in this study (and quarantine of their close contacts) was probably unnecessary given the low likelihood of transmissibility suggested by the Ct values. Nevertheless, due to the uncertainty around these cases, it was reasonable to take a conservative approach in the context of an ongoing pandemic. The uncertainty about such cases underscores the need for further investigation of patients with recurrent positive tests so that they may have their disease status correctly classified, which would enable more effective counseling regarding individual behaviors and a more targeted public health response.

Finally, these results suggest the need for clear public health risk communication to previously infected individuals, particularly regarding the risk of reinfection and the potential mitigating effects of vaccination. Previously infected individuals who believe that they are immune may be less likely to use masks, to adhere to social distancing requirements, or to receive the vaccine. Recent data has shown that service members who were previously infected with COVID-19 were less likely to receive vaccination, even after adjusting for demographics, comorbidities, and other factors.8 Previously infected individuals who remain unvaccinated have been shown to have a 2.3 times higher likelihood of reinfection compared to those who were previously infected and then vaccinated,6 and these individuals may then transmit the infection to others. Public health and medical personnel should consider specifically targeting previously infected individuals for vaccination campaigns.

Author affiliations: USAMEDDAC, Fort Jackson, SC (COL Kwon, 1LT Shadwick, and COL Hall); GEIS, AFSHD, Silver Spring, MD (Dr. Bazaco, Dr. Morton, and Ms. Hartman); Department of Preventive Medicine & Biostatistics, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, MD (COL Mancuso).

Disclaimer: The opinions and assertions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Uniformed Services University, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

References

- Nonaka CKV, Franco MM, Graf T, et al. Genomic Evidence of SARS-CoV-2 Reinfection Involving E484K Spike Mutation, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27(5):1522–1524.

- Zucman N, Uhel F, Descamps D, Roux D, Ricard JD. Severe reinfection with South African SARS-CoV-2 variant 501Y.V2: A case report. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;ciab129.

- Harrington D, Kele B, Pereira S, et al. Confirmed reinfection with SARS-CoV-2 variant VOC-202012/01. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;ciab104.

- Korea Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. Findings from Investigation and Analysis of re-positive cases. 18 May 2020. Korea Central Disaster Control and Prevention (KCDC): Seoul, Korea.

- Hall VJ, Foulkes S, Charlett A, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection rates of antibody-positive compared with antibody-negative health-care workers in England: a large, multicentre, prospective cohort study (SIREN). Lancet. 2021;397(10283):1459–1469.

- Cavanaugh AM, Spicer KB, Thoroughman D, Glick C, Winter K. Reduced risk of reinfection with SARS-CoV-2 after COVID-19 vaccination-Kentucky, May-June 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(32):1081–1083.

- Letizia AG, Ge Y, Vangeti S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 seropositivity and subsequent infection risk in healthy young adults: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9(7):712–720.

- Lang MA, Stahlman S, Wells NY, et al. Disparities in COVID-19 vaccine initiation and completion among active component service members and health care personnel, 11 December 2020-12 March 2021. MSMR. 2021;28(4):2–9.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) 2020 Interim Case Definition, Approved April 5, 2020. Updated 5 Aug 2020. Accessed 20 April 2021. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nndss/conditions/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19/case-definition/2020/

- US Army Public Health Center. SURVEILLANCE OF COVID-19 IN THE DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE. Technical Information Paper No. 98-122-0720. Accessed 20 April 2021. https://phc.amedd.army.mil/PHC%20Resource%20Library/cv19-surveillance_in_the_DOD.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Investigative criteria for suspected cases of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection (ICR). Updated 27 Oct 2020. Accessed 20 April 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/php/invest-criteria.html

- Azam M, Sulistiana R, Ratnawati M, et al. Recurrent SARS-CoV-2 RNA positivity after COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):20692.

- Vancsa S, Dembrovszky F, Farkas N, et al. Repeated SARS-CoV-2 positivity: analysis of 123 cases. Viruses. 2021;13(3):512.

- Gousseff M, Penot P, Gallay L, et al. Clinical recurrences of COVID-19 symptoms after recovery: Viral relapse, reinfection or inflammatory rebound? J Infect. 2020;81(5):816–846.

- Tomassini S, Kotecha D, Bird PW, Folwell A, Biju S, Tang JW. Setting the criteria for SARS-CoV-2 reinfection - six possible cases. J Infect. 2021;82(2):282–327.

- Rhoads D, Peaper DR, She RC, et al. College of American Pathologists (CAP) Microbiology Committee Perspective: Caution must be used in interpreting the Cycle Threshold (Ct) value. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72(10):e685–e686.