What Are the New Findings?

During 2016–2020, Osteoarthritis (OA) and spondylosis were diagnosed in 39,949 and 60,475 active component service members, respectively. Among those aged 25 or older, overall rates of both conditions were highest among Army and Marine Corps members. In all demographic and military subgroups examined, the knee joint was the anatomic site most frequently affected by OA. Overall rates of site-specific OA diagnoses varied by sex, race/ethnicity group, service, and military occupation.

What Is the Impact on Readiness and Force Health Protection?

OA and spondylosis can result in significant pain, limitations in function, and progressive disability. As such, these conditions can affect medical readiness of service members through increased limited duty days, decreased deployability rates, and increased medical separation rates.

Abstract

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common adult joint disease and accounts for significant morbidity burdens among U.S. civilian and military populations. During 2016–2020, the crude overall rates of incident OA and spondylosis diagnoses among U.S. active component service members were 630.9 per 100,000 person-years (p-yrs) and 958.F per 100,000 p-yrs, respectively. Crude annual rates of both conditions decreased markedly from 2016 through 2020 with declines evident in all of the demographic and military subgroups examined. Compared to their respective counterparts, crude overall rates of OA diagnoses were highest among male service members, those aged 35 or older, non-Hispanic Black service members, Army members, and those working in health care occupations. Crude overall rates of spondylosis diagnoses were highest among those aged 30 or older, non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Black service members, Army members, and those in health care and communications/intelligence occupations. More than two-thirds of all incident OA diagnoses involved the knee (38.8%) or shoulder (28.4%). Differences in anatomic site-specific rates of OA were apparent by sex, race/ethnicity group, service, and military occupation. Additional research to identify military-specific equipment and activities that increase the risk of acute and chronic damage to joints would be useful to develop, test, and implement practical and effective countermeasures against OA and spondylosis among military members in general and those in high-risk occupations specifically.

Background

Osteoarthritis (OA), the most common adult joint disease, is primarily a degenerative disorder of the entire joint organ, including the subchondral bone, synovium, and periarticular structures (e.g., tendons, ligaments, bursae).1,2 Although OA has traditionally been viewed as a degenerative disorder arising largely from wear and tear, increasing evidence suggests that excessive or abnormal joint loading also stimulates joint tissue cells to produce proinflammatory factors and proteolytic enzymes that mediate joint tissue destruction.3,4 The swelling that generally occurs in early OA is the result of an increased production of proteoglycans which reflects the chondrocytes' (cartilage cells) efforts to repair articular cartilage damage.5 However, this process is accompanied by the presence of proinflammatory cytokines which result in the deterioration of chondrocyte metabolism and limit self-regeneration of cartilage.5 These processes form a positive feedback loop that is a key driver in the pathology of OA.5 As OA progresses, proteoglycan levels fall causing the cartilage to soften and lose elasticity, which further compromises joint surface integrity.2 Over time, microscopic flaking and splitting develop on the surface of the articular cartilage with loss of cartilage leading to a reduction in joint space.2 In severe cases of OA, erosion of the damaged cartilage may progress until the underlying bone is exposed.1 The destruction of articular cartilage and remodeling of subarticular bone associated with OA can result in significant pain, joint effusion (abnormal accumulation of fluid in or around a joint), limitations in function, and progressive disability.6

OA predominantly involves the weight-bearing joints, including the knees, hips, cervical and lumbosacral spine, ankles, and feet.2 Other commonly affected joints include the shoulder, the wrist and the joints of the hand.7

Spondylosis, often referred to as OA of the spine, is characterized by degenerative changes in the vertebral discs, joints, and vertebral bodies.8 The pathophysiology of spondylosis is not fully understood.8 The sequence of changes seen in spondylosis generally begins with desiccation of the vertebral disc; the resultant decrease in disc height weakens the ligamentous outer portion of the intervertebral disc.9 These changes lead to increased stress at key points which, in turn, results in osseous and ligamentous hypertrophy and osteophyte formation.9,10 Individuals affected by spondylosis often report neck and back pain that is increased by motion and/or stiffness with limitation of motion.8,9 In severe cases, spondylosis may cause pressure on nerve roots and spinal stenosis (narrowing of the spinal canal).8–10

Key risk factors for the development of OA include advancing age,11 female sex,12 family history,11,13 obesity,14 specific bone/joint shapes,14 high bone density/mass,15 repetitive joint loading,16–22 and traumatic joint injury (e.g., during occupational or recreational activities).23–25 OA is a leading cause of pain and functional impairment in working age adults and the elderly26–28; as such, OA accounts for significant morbidity burdens among U.S. civilian and military populations29–33 and its management requires substantial health care resources and incurs considerable costs.34,35 Between 2008 and 2014, the average annual per-person medical costs attributed to OA was $11,052;35 annual all-cause costs (both direct and indirect) attributed to OA averaged $468 billion nationally during this period.35

Despite the significant morbidity and health care costs attributable to OA, there are relatively few published, U.S. population-based estimates of the incidence of this condition. Estimates of the incidence of OA vary depending on the definition of OA employed (e.g., symptomatic, radiographic, self-reported, or physician-diagnosed), the specific joint(s) evaluated, and study population.14 Studies that have focused on estimating incidence rates of OA have typically generated estimates related to a single joint.30,36–38 Moreover, relatively few studies have focused on the incidence of OA in younger and physically active populations. In a 2011 report, Cameron and colleagues estimated that, from 1999 through 2008, incidence rates of OA diagnoses were significantly higher among U.S. active duty service members than comparably aged Canadian civilians.39 Likely causes, at least in part, for the relatively high rates of OA among military members include the physical stresses associated with military training (e.g., running in formation), operations (e.g., heavy load bearing, prolonged wearing of body armor), and occupations (e.g., drivers and crews of military vehicles, paratroopers, health care workers).21,22, 30, 40–43 Given their potential exposure to repetitive joint loading activities and rigorous occupational tasks, active component U.S. service members are a high-risk population of epidemiologic interest in general and of military medical concern. Specifically, OA can affect readiness through increased limited duty days, decreased deployability rates, and increased medical separation rates.31,32,41,44, 45

In 2016, the MSMR reported on the incidence of OA and spondylosis among active component U.S. service members from 2010 through 2015.46 The current analysis updates this earlier work by summarizing the numbers, rates, trends, and demographic and military characteristics of active component service members who were diagnosed with OA or spondylosis during 2016–2020.

Methods

The surveillance population consisted of all individuals who served in the active component of the U.S. Army, Navy, Air Force, or Marine Corps at any time between Jan. 1, 2016 and Dec. 31, 2020. Records of both inpatient and outpatient health care encounters documented in the Defense Medical Surveillance System (DMSS) were searched to identify cases of OA/spondylosis. Diagnoses were ascertained from administrative records of all inpatient and outpatient encounters of individuals who received medical care in fixed (i.e., not deployed or at sea) medical facilities of the Military Health System (MHS) or civilian facilities in the Click to closePurchased CareThe TRICARE Health Program is often referred to as purchased care. It is the services we “purchase” through the managed care support contracts.purchased care system documented in the DMSS. Data on care provided in deployed settings were not included in this analysis.

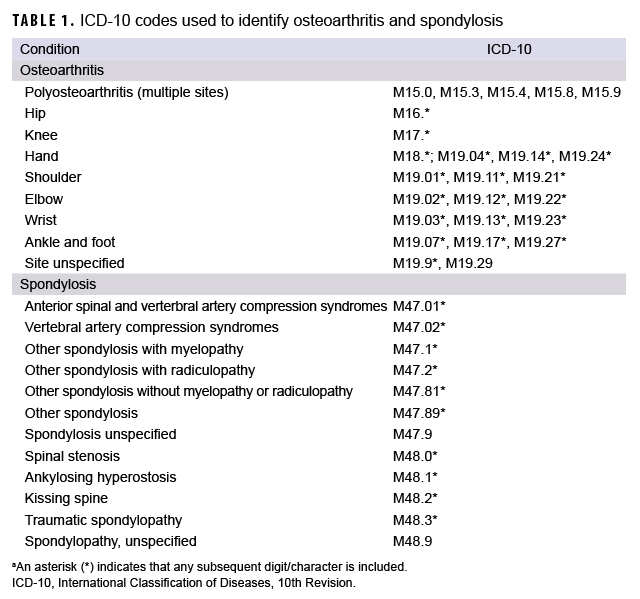

An incident case of OA or spondylosis was defined by a record of a hospitalization or records of at least 2 outpatient medical encounters within 2 years that included any of the case-defining International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) codes in any diagnostic position (Table 1). The incidence date was the date of the first case-defining hospitalization or outpatient medical encounter that included a diagnosis of OA or spondylosis. An individual could be counted as a case of OA or spondylosis once per lifetime. Each individual could be diagnosed as an incident case of OA and an incident case of spondylosis only 1 time each during the surveillance period; that is, incident cases of OA could be diagnosed as spondylosis cases and vice versa. Prevalent cases (i.e., individuals with incident encounters prior to the surveillance period) were excluded from the analysis. ICD-9 codes for OA and spondylosis (715.* and 721.*, respectively) were used to exclude prevalent cases.

Incidence rates were calculated as incident OA or spondylosis diagnoses per 100,000 person-years (p-yrs) of active component service. Crude overall incidence rates for both conditions were computed for each year of the surveillance period and stratified by key demographic and military characteristics (age group, sex, race/ethnicity group, branch of military service, rank and military occupation).

Multivariable negative binomial regression models were used to compute adjusted incidence rate ratios (AIRRs) of OA and spondylosis for the military occupation categories with pilot/air crew as the reference group. Multivariable models were adjusted for age group (reference group=20–24 years), sex (reference group=male), race/ethnicity group (reference group=non-Hispanic White), and service branch (reference group=Marine Corps). All analyses were carried out using SAS/STAT software, version 9.4 (2014, SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Site-specific ICD-10 codes were used to summarize the anatomical locations of OA (Table 1); if an individual received more than 1 OA diagnosis, site-specific diagnoses (e.g., shoulder, knee) were prioritized over non-site-specific diagnoses (site unspecified); polyosteoarthritis (multiple sites) was prioritized over site unspecified diagnoses. If multiple diagnosis codes of the same specificity occurred during the surveillance period, the earliest occurring site-specific code was selected. If multiple diagnosis codes of the same specificity occurred in the same earliest encounter, diagnoses were prioritized by diagnostic position (diagnosis 1 > diagnosis 2, etc.). To examine counts and percentages of OA cases with 2 or more diagnoses of different specified anatomic sites during the surveillance period, diagnoses for site unspecified and polyosteoarthritis were excluded. OA cases with 2 or more diagnoses of different specified anatomic sites were categorized as having OA diagnoses of 2, 3, or 4 different specified sites.

Results

Osteoarthritis

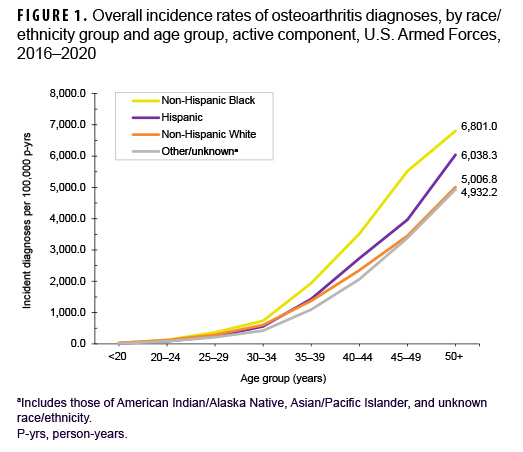

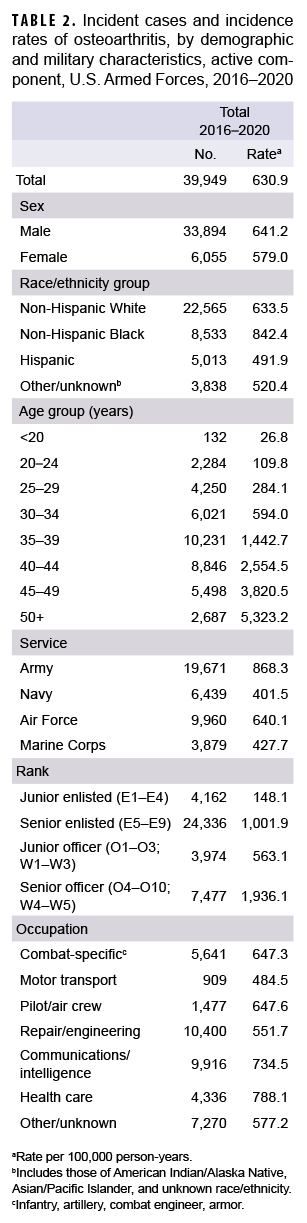

During the 5-year surveillance period, a total of 39,949 active component service members received incident diagnoses of OA, for a crude (unadjusted) overall incidence rate of 630.9 per 100,000 p-yrs (Table 2). The crude overall rate was higher among male compared to female service members (641.2 and 579.0 per 100,000 p-yrs, respectively) (Table 2). The patterns of overall rates by age group were similar for both sexes through age 44; however, among those aged 45 or older, overall rates were higher among female compared to male service members (data not shown). Overall rates of OA diagnoses increased markedly with increasing age, with the rate among service members aged 25–29 over 10 times the rate among those under age 20; rates doubled for each 5-year age interval from ages 20–24 through 35–39, but, thereafter, the increases by age group were approximately 80%, 50%, and 40%, respectively. Non-Hispanic Black service members had the highest crude overall rate of incident OA diagnoses (842.4 per 100,000 p-yrs) compared to those in other race/ethnicity groups (Table 2). The lowest crude overall rate by race/ethnicity group was observed among Hispanic service members (491.9 per 100,000 p-yrs). Further stratification by age group showed that, among those 25 years or older, non-Hispanic Black service members had the highest overall rate of OA diagnoses and those in the other/unknown race/ethnicity group (includes American Indian/Alaska Native service members, Asian/Pacific Islander service members, and those of unknown race/ethnicity) had the lowest rate (Figure 1).

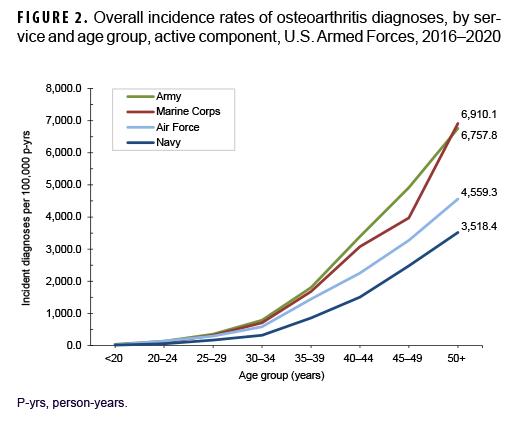

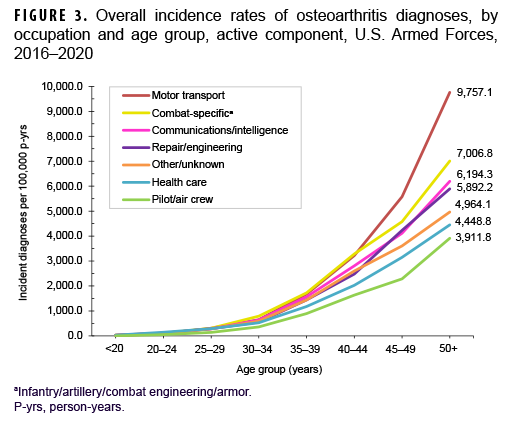

Across the services, crude overall incidence rates of OA diagnoses were highest among Army members (868.3 per 100,000 p-yrs) and lowest among Navy members (401.5 per 100,000 p-yrs) (Table 2). Examination by service and age group showed that, among those aged 25 or older, overall rates were highest among Army and Marine Corps members, respectively (Figure 2). The overall rates of incident OA diagnoses among senior enlisted service members and senior officers were more than 6 and 3 times, respectively, those among their junior, and generally younger, counterparts (Table 2). Crude overall incidence rates of OA diagnoses were highest among service members in health care and communications/intelligence occupations (788.1 and 734.5 per 100,000 p-yrs, respectively) and lowest among those working in motor transport (484.5 per 100,000 p-yrs). However, among service members 30 years or older, rates of OA diagnoses were higher among those in motor transport and combat-specific occupations than those in any other occupational group (Figure 3). Moreover, among service members 45 years or older, rates of incident OA diagnoses were markedly higher among those working in motor transport than among those in any other occupational group. Of note, in all age groups 20 years or older, rates of OA diagnoses were lowest among service members working as pilots/air crew.

Multivariable regression analysis revealed that, compared to their respective counterparts working as pilots/air crew, service members in all other occupational groups showed significantly elevated rates of OA after adjusting for age group, sex, race/ethnicity group, and service branch (data not shown). Rates of OA diagnoses were approximately 60% higher among those in combat-specific (AIRR=1.64; 95% CI: 1.51–1.77), motor transport (AIRR=1.60; 95% CI: 1.45–1.76), and repair/engineering occupations (AIRR=1.59; 95% CI: 1.47–1.71) compared with pilots and air crew members (data not shown). Service members in communications/intelligence, other/unknown, and health care occupations had rates of OA that were 1.5, 1.4 and 1.3 times those of service members working as pilots/air crew, respectively (data not shown).

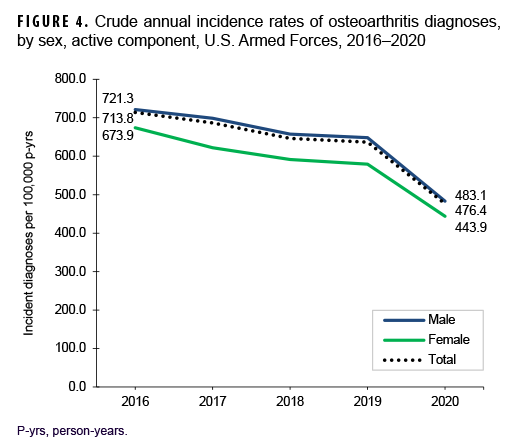

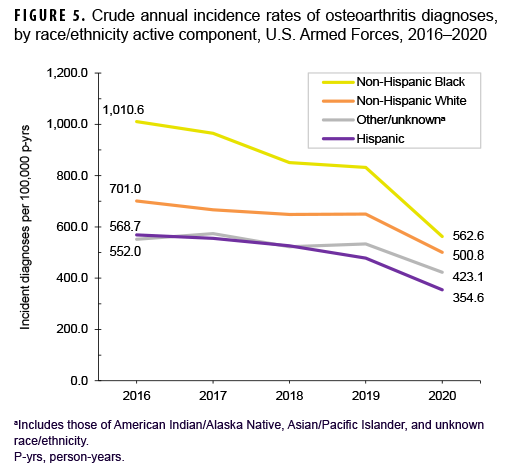

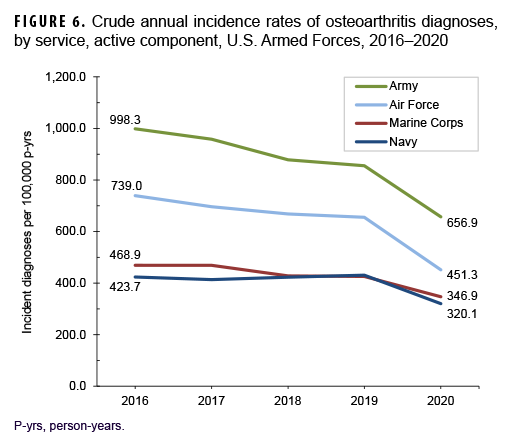

Over the course of the surveillance period, crude annual rates of incident OA diagnoses decreased from a high of 713.8 per 100,000 p-yrs in 2016 to a low of 476.4 per 100,000 p-yrs in 2020 (33.3% decrease), with the greatest decline occurring between 2019 and 2020 (Figure 4). Throughout the 5-year period, crude annual incidence rates of OA diagnoses were consistently higher among male than female service members. Stratification by age group showed that rates of OA diagnoses remained relatively stable during the first 4 years of the surveillance period among those in the 3 oldest age groups (40 years or older), with pronounced decreases between 2019 and 2020 (data not shown). Among service members aged 39 or younger, declines in OA rates were relatively steady over time (data not shown). Over the surveillance period, crude annual rates of OA decreased among service members in all race/ethnicity groups with the most pronounced decreases among non-Hispanic Black (44.3%) and Hispanic service members (37.6%) (Figure 5). Annual rates of incident OA diagnoses decreased in all services with the greatest declines over time among members of the Air Force (38.9%) and Army (34.2%) (Figure 6). Rates also decreased over the course of the 5-year period among service members in all occupational groups (data not shown).

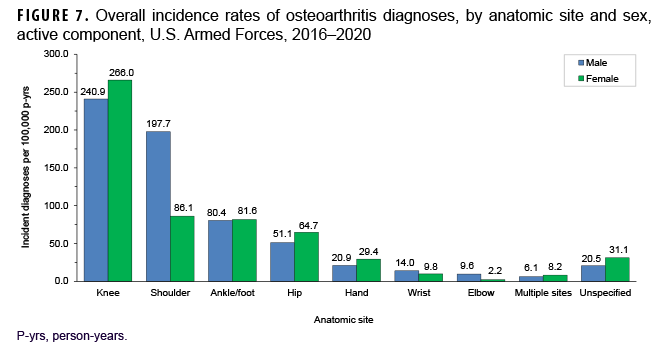

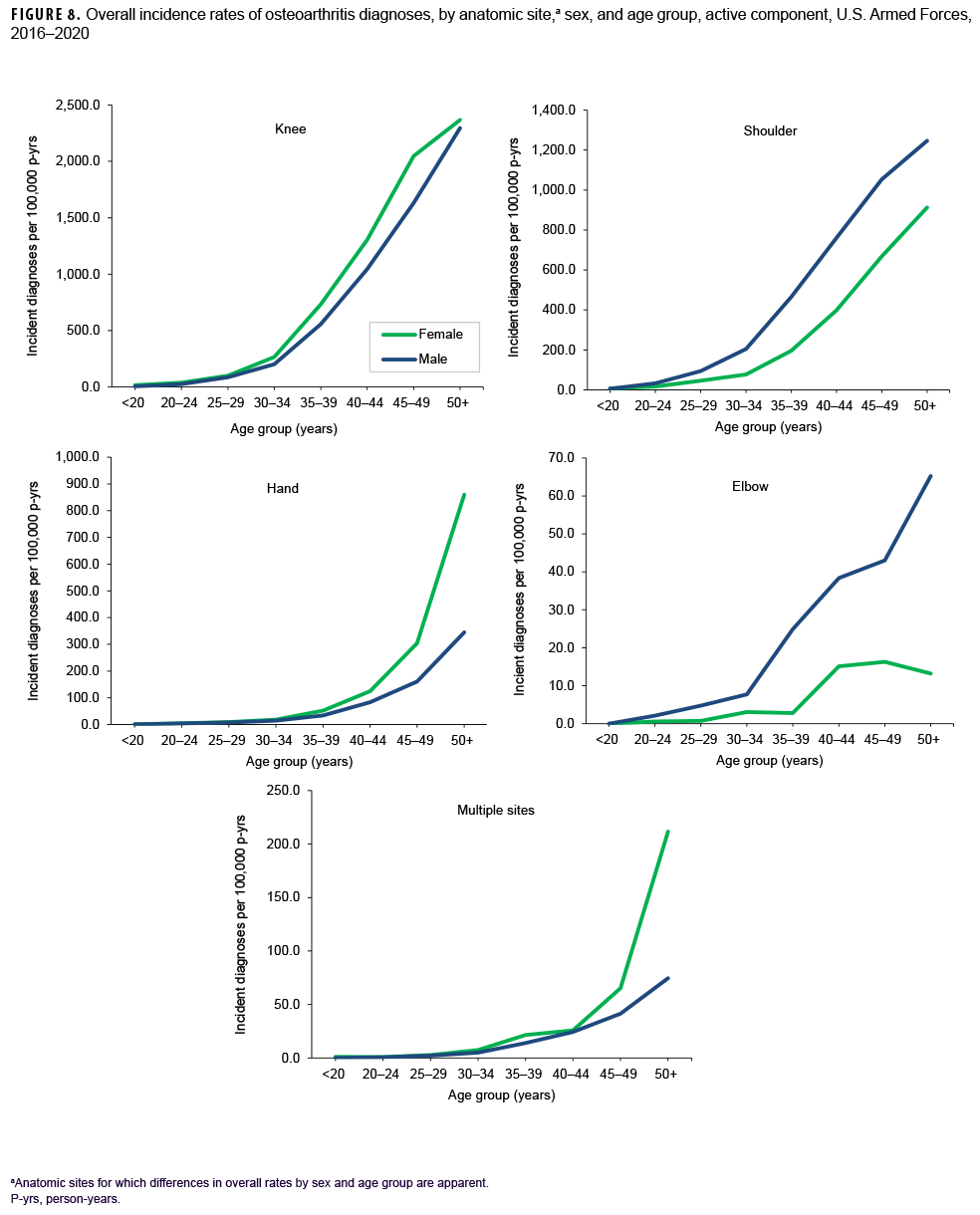

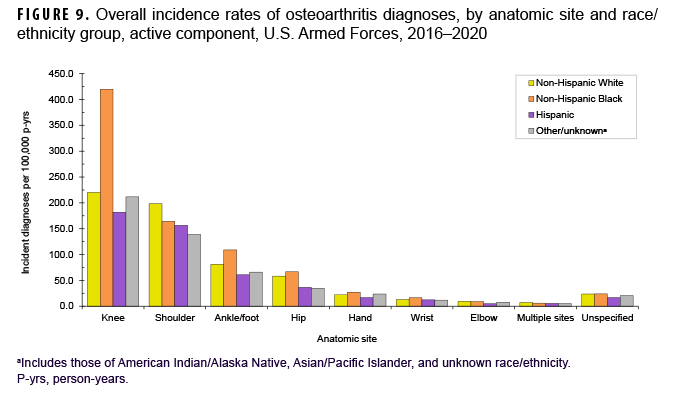

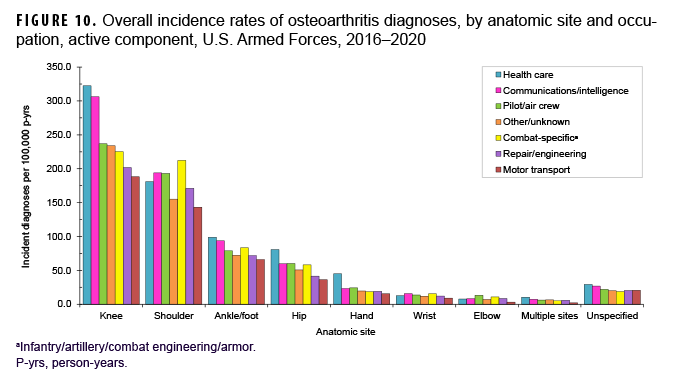

More than two-thirds of all incident OA diagnoses involved the knee (38.8%) or shoulder (28.4%) (data not shown). Crude overall rates of incident diagnoses of OA of the knee, hip, hand, multiple sites, and unspecified sites were 10%–52% higher among female than male service members (Figure 7). Among male service members, overall rates of diagnoses of OA of the elbow and shoulder were 4.4 and 2.3 times, respectively, those among female service members. Examination by sex and age group showed that the age at which several of these differences in rates became apparent varied by anatomic site. For example, the difference in overall rates of incident diagnoses of OA of the shoulder among male and female service members is apparent in those aged 25 or older while the difference in rates of diagnoses of OA of the hand are evident in those 35 years or older (Figure 8). Further stratification by race/ethnicity group revealed that the overall incidence rates of diagnoses of OA of the knee and ankle/foot among non-Hispanic Black service members were 90.6% and 34.1% higher, respectively, than those among non-Hispanic White service members (Figure 9). Across the services, overall rates of incident diagnoses of OA of all sites were highest among Army and Air Force members (data not shown). Overall rates were lowest among Navy members for OA of all sites except the hand and wrist. Examination by occupational group revealed that the overall rates of diagnoses of OA of the knee among those working in health care and communications/intelligence occupations were at least 1.9 and 1.3 times, respectively, the rates among service members in other occupational groups (Figure 10). In addition, the overall rate of incident diagnoses of OA of the hand among health care workers was 1.9 or more times those of service members in other occupational groups. The overall rate of shoulder OA among service members in combat-specific occupations was 9.4%–48.0% higher than rates among those in other occupational groups.

Spondylosis

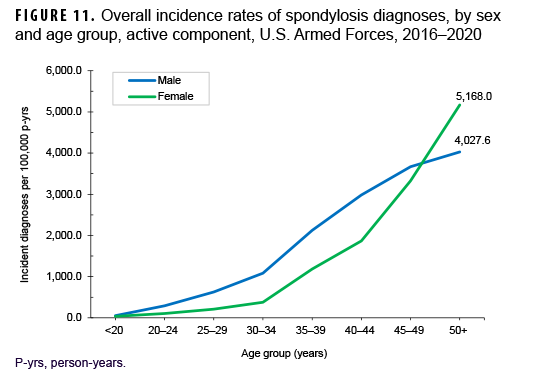

Between 2016 and 2020, a total of 60,475 active component service members received incident diagnoses of spondylosis, for a crude overall incidence rate of 958.2 per 100,000 p-yrs (Table 3). The crude overall rates of incident spondylosis diagnoses were broadly comparable among male and female service members. Similar to OA, there was a marked rise in overall incidence rates of spondylosis diagnoses with increasing age. Further stratification by sex showed that the pattern of increase with advancing age was roughly linear for male service members and approximately exponential for female service members (Figure 11). Overall incidence rates of spondylosis diagnoses among male service members aged 20–44 were higher than comparably aged female service members. However, among those aged 45–49, overall spondylosis rates were very similar for service members of both sexes; however, among those 50 or older, the rate of OA diagnoses was considerably higher among female than male service members.

Crude overall rates of incident spondylosis diagnoses were markedly higher among non-Hispanic White (1,005.3 per 100,000 p-yrs) and non-Hispanic Black service members (1,000.6 per 100,000 p-yrs) compared to those among Hispanic service members (833.6 per 100,000 p-yrs) and those of other or unknown race/ethnicity (843.6 per 100,000 p-yrs) (Table 3). Examination by race/ethnicity group and age group showed that the patterns of increase in rates with increasing age among non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic service members were similar through age 44 but then diverged, with non-Hispanic Black service members demonstrating markedly higher rates in the oldest 2 age groups (45 years or older) compared to Hispanic service members (data not shown). The patterns of increasing overall rates of spondylosis with advancing age among non-Hispanic White service members and those in the other/unknown race/ethnicity group were broadly similar across all age groups (data not shown).

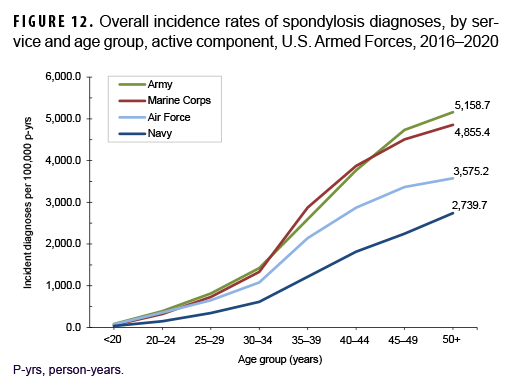

Across the services, overall incidence rates of spondylosis diagnoses were highest among Army members (1,267.5 per 100,000 p-yrs) and lowest among Navy members (577.4 per 100,000 p-yrs) (Table 3). Among those aged 25 or older, overall rates were highest among Army and Marine Corps members and intermediate among Air Force members; rates were lowest among Navy members in every age group (Figure 12). The overall rates of incident spondylosis diagnoses among senior enlisted service members and senior officers were more than 4 and 2 times, respectively, those among their respective junior counterparts (Table 3). Compared to those in other occupational groups, crude overall incidence rates of spondylosis diagnoses were highest among service members working in health care and communications/intelligence (1,161.6 and 1,102.0 per 100,000 p-yrs, respectively) occupations and lowest among those in the other/unknown occupational group (813.9 per 100,000 p-yrs). Further stratification by age group showed that, among service members 30 years or older, rates of spondylosis diagnoses were higher among those in combat-specific and motor transport occupations than among those in any other occupational groups; in all age groups 20 years or older, rates were lowest among pilots/air crew (data not shown).

Results of multivariable regression analyses showed that, relative to pilots/air crew members, service members in all other occupational groups showed significantly elevated rates of spondylosis after adjusting for key covariates (data not shown). Service members in motor transport (AIRR=1.64; 95% CI: 1.49–1.80), repair/engineering (AIRR=1.53; 95% CI: 1.41–1.65), and combat-specific (AIRR=1.52; 95% CI: 1.40–1.66) occupations had rates of spondylosis that were at least 1.5 times those of service members working as pilots/air crew (data not shown). Service members in communications/intelligence, health care, and other/unknown occupations had rates of spondylosis that were 1.4, 1.4, and 1.3 times those of service members working as pilots/air crew, respectively (data not shown).

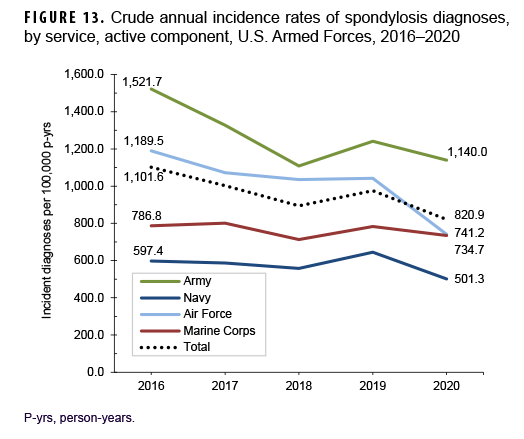

Between 2016 and 2020, crude annual rates of incident spondylosis diagnoses among active component service members decreased from a high of 1,101.6 per 100,000 p-yrs in 2016 to a low of 820.9 per 100,000 p-yrs in 2020 (25.5%) (Figure 13). The greatest decline in incidence occurred between 2016 and 2018 after which the rate increased to 975.1 per 100,000 p-yrs in 2019 and then decreased to 820.9 per 100,000 p-yrs in 2020. Throughout the 5-year period, annual incidence rates of spondylosis diagnoses decreased in male and female service members with both sexes showing a similar pattern of change over time (data not shown). Annual rates decreased among service members in all race/ethnicity groups with the greatest decrease (31.6%) among non-Hispanic Black service members (data not shown). During the surveillance period, annual rates of incident spondylosis diagnoses decreased in all services with the greatest declines over time among members of the Air Force (37.7%) and Army (25.1%) (Figure 13). Rates also decreased over the course of the 5-year period among service members in all occupational groups (data not shown).

Editorial Comment

The results of the current study show that the crude annual incidence rates of OA and spondylosis diagnoses among active component service members decreased markedly (33.3% and 25.5%, respectively) from 2016 through 2020. During the 5-year period, annual rates of incident diagnoses of OA and spondylosis decreased in all of the demographic and military subgroups examined. These decreases in annual rates may be due, at least in part, to an overall decrease in combat operations during the study period and thus a possible decrease in the rates of extremity trauma. It is important to note that the drops in the incidence rates of diagnoses of both conditions between 2019 and 2020 may have been due, at least in part, to the COVID-19 pandemic. COVID-19 has led to decreases in the utilization of many types of health care,47,48 ranging from preventive care to chronic disease management and emergency department visits.49 Results of a web-based survey of a representative sample of U.S. adults aged 18 or older conducted in June 2020 showed that 40% of respondents reported having delayed or avoided seeking routine or emergent medical care because of the pandemic.50

The findings of this analysis re-emphasize the strong relationships between clinically significant OA and spondylosis and advancing age.14 Across the age range of U.S. military members, rates of incident diagnoses of OA and spondylosis increased markedly with advancing age. This finding underscores the importance of accounting for the effects of age when assessing the effects of other potential risk factors.

Subgroup analysis showed that male service members had a higher crude overall rate of incident OA diagnoses compared to female service members. This result is consistent with the results of the 2016 MSMR analysis;46 however, Cameron and colleagues' study of active duty service members during 1999–2008 reported higher crude and age-adjusted incidence estimates among female than male service members.39 The finding that, among individuals 45 years of older, rates of OA were higher among female than male service members is in line with many published studies of OA prevalence and incidence in the general U.S. population.11,14,15 Compared to their respective counterparts, non-Hispanic Black service members, Army members, and those working in health care operations had the highest crude overall incidence rates of OA diagnoses. Stratification by age group showed that the highest overall rates of OA diagnoses were among non-Hispanic Black service members in those aged 20 or older, Army and Marine Corps members in those aged 25 or older, and those in motor transport and combat-specific occupations in service members aged 30 or older.

Cameron et al. described similar findings by race/ethnicity group among active duty U.S. military members between 1999 and 2008.39 However, few other studies have examined the relationship between race and the occurrence of osteoarthritis in general. Analysis of 2010–2012 National Health Interview Study data indicated that, among individuals aged 18 or older, non-Hispanic Black adults had a prevalence of physician-diagnosed OA similar to that of non-Hispanic White adults.29 Using data from the Johnston County (NC) Project, Nelson and colleagues reported that African Americans were more likely to develop multiple large-joint OA (knee, hip, spine) compared to those in other racial groups.50 Scher et al. reported similar findings specific to OA of the hip among active duty U.S. service members during 1998–2006.36 Results of several studies suggest that anatomic, neuromuscular, and biomechanical differences by race/ethnicity group (e.g., higher bone density/mass51 and greater muscle mass52) may be linked to altered weight bearing and loading associated with joints in the lower extremity among non-Hispanic Blacks.

In all demographic and military subgroups examined, the knee joint was the anatomic site most frequently affected by OA. This finding is consistent with results of many studies of the occurrence of OA in U.S. general and military populations.11,14,15,30,39 Differences were observed in anatomic site-specific rates of OA by sex, race/ethnicity, service, and military occupation. Crude overall rates of incident diagnoses of OA of the knee, hip and hand were higher among female than male service members; rates of OA of the shoulder and elbow were higher among male than female service members. Similar sex differences in the anatomic site-specific occurrence of OA have been reported from studies of the U.S. civilian population.11,14,15 Overall incidence rates of diagnoses of OA of the knee and ankle/foot among non-Hispanic Black service members were markedly higher than those among non-Hispanic White service members. This finding of differences in OA site by race/ethnicity group mirrors results of studies of knee and hip OA in the general U.S. population.14,25,54

Across the services, overall rates of incident diagnoses of OA of all sites were highest among Army and Air Force members. The finding that crude and age-adjusted incidence rates of OA diagnoses were higher among Army members than among those in the other services is consistent with results described by Cameron et al. among active duty service members.39 Scher and colleagues reported similar results for the incidence rate of primary hip OA among active duty service members.36

Differences in rates of incident OA diagnoses by military occupational group were apparent in both the crude and age-stratified results. The finding that, among service members aged 30 or older, those in the motor transport occupation category had the highest age-adjusted incidence rates of OA warrants additional study. Overall rates of diagnoses of OA of the knee among those working in health care and communications/intelligence occupations were markedly higher than rates among service members in other occupational groups. In addition, the overall rate of incident diagnoses of OA of the hand among health care workers was considerably higher than those of service members in other occupational groups. Service members in combat-specific occupations had the highest overall rate of shoulder OA compared to those in other occupational groups.

In the current analysis, service members working as pilots and other air crew had significantly lower crude and adjusted rates of incident diagnoses of both OA and spondylosis than those in all other occupational groups. AIRRs showed that, compared to their respective counterparts working as pilots/air crew, service members in all other occupational groups showed significantly elevated risk of OA and spondylosis after adjusting for key covariates. These findings for spondylosis were contrary to expectations given evidence that certain occupational conditions (e.g., helmets and headgear, awkward postures during flight, flight accelerations, whole body vibrations) associated with flying may increase risk of degenerative changes in the cervical and lumbar spines of pilots.55–57 However, other studies have found no relationships between musculoskeletal disorders experienced by pilots and job-related factors, especially regarding full-body vibration.58,59 Results of the current analysis may reflect a tendency among military aviators and crewmen to seek care only for conditions that significantly interfere with their military occupational duties.

Many military occupations entail physically demanding work. Physical requirements of military service have been broadly characterized as climbing, digging, walking, marching and running, lifting and carrying, lifting and lowering, and pushing and pulling.60 The preponderance of the published literature on the association between physically demanding work and OA has focused on OA of the hip and knee. Physically demanding jobs have been strongly associated with OA of both of these joints.14,61–63 Recent reviews of the literature have found moderate to good evidence that heavy occupational lifting is associated with an increased risk of OA of the knee and the hip.21,22 Moreover, results of some studies suggest that the combination of tasks that involve heavy lifting and kneeling64 or squatting65 further increases the risk of developing knee OA. In occupations that involve excessive squatting, this movement alone appears to be associated with knee OA.21 The forces involved in squatting can have long-term adverse effects on both the mechanical functions of the knee joint and the structural integrity of the articular cartilage within the joint.66 Activities that require knee bending or kneeling have also been associated with the development of knee OA.21,22 A recent systematic review and synthesis of 69 occupational health and safety studies from 23 countries demonstrated moderate to strong evidence for no increased risk of hip or knee OA related to sitting, standing and walking, climbing ladders, or driving.67

Results of this same review and synthesis indicated that there was mixed or insufficient evidence related to work and OA of the hands, spine, and multiple joints.67 Examination of studies focused on OA of the hands yielded moderate evidence for no effect of highly repetitive tasks on the development of wrist/hand/finger OA.66 Evidence was mixed related to an association between lifting activities and physically demanding work and the development of spondylosis and OA in multiple joints, respectively.67

Physically demanding tasks such as carrying heavy loads, kneeling, and squatting are required elements of military training and many military occupations. Avoiding activities that require such tasks is not possible or desirable given that training must closely replicate expected combat/occupational actions.54,59 Taking these constraints into account, prevention efforts could more reasonably be focused on minimizing initial injuries where possible,7,68 ensuring complete rehabilitation of injuries when they do occur, achieving adequate strength around affected joints, and maintaining optimal body mass index.69

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the results of this analysis. First, criteria for diagnosing OA and spondylosis in active component service members may vary across health care providers and clinical settings, as well as in relation to the occupational duties of those affected. Some health care providers may diagnose these conditions based on symptoms alone, while others may require radiographic evidence of arthritic damage to the joints involved before reporting specific diagnoses in medical records. It is possible that the decline in incidence of both OA and spondylosis in the last year of the surveillance period may reflect the fact that some individuals with their first outpatient visits with qualifying diagnoses of OA or spondylosis in 2020 may not have had sufficient follow-up observation periods to have had second such visits, a necessary criterion to be counted as a case. In addition, this report summarizes diagnoses of OA and spondylosis that were reported on standardized records of hospitalizations and outpatient encounters in fixed U.S. military and civilian (i.e., purchased care) medical facilities if reimbursed through the MHS. Records of care received at civilian medical facilities outside the MHS but not reimbursed through the MHS were not available for this analysis. As a result, the numbers and rates of incident diagnoses reported here likely underestimate the actual numbers and rates of incident diagnoses of both conditions.

Also, there are limitations to the generalizability of the results because of the characteristics of the population. Active component service members are relatively young, healthy, physically active, and employed, and as such, may have unique risks (e.g., branch of service) and protective factors (e.g., lower body mass index). Also, military members have access to health care at no personal expense; as such, conditions such as OA and spondylosis could be diagnosed and medically documented more completely and earlier in their clinical courses than among many U.S. civilians. Thus, generalizations of the observed results should be limited to similar groups. Furthermore, it is difficult to determine differences in rates of degenerative OA versus post-traumatic OA, especially in the active component military population. However, a retrospective cohort study of U.S. Army soldiers from 2008 through 2012 demonstrated that soldiers who experienced knee joint trauma while on active duty were more than 5 times as likely to be diagnosed with OA of the knee during their military career compared to their respective counterparts with no knee joint injury.70

Additionally, this report summarizes the numbers and rates of incident (first time per person) diagnoses of the conditions of interest. As such, the results do not necessarily indicate the prevalence or military-operational impacts of the conditions in the Armed Forces. For example, service members with disabling OA or spondylosis may leave active military service earlier than their unaffected counterparts; if so, the continuous attrition from service of those affected would lower the prevalence, military operational impacts, and health care costs associated with the conditions among those who remain. Also, individuals who are unable to perform their occupation-specific duties due to OA or spondylosis may change occupations or separate from military service; if so, the prevalence of OA or spondylosis would be relatively higher in those occupations that retain service members with these conditions.

Finally, medical data from sites that used the new electronic health record for the Military Health System, MHS GENESIS, between July 2017 and October 2019 are not available in the DMSS. These sites include Naval Hospital Oak Harbor, Naval Hospital Bremerton, Air Force Medical Services Fairchild, and Madigan Army Medical Center. Therefore, medical encounter data for individuals seeking care at any of these facilities from July 2017 through October 2019 were not included in the current analysis.

This report provides a descriptive summary of incidence rates of clinically significant OA and spondylosis among active component service members. Observed differences in incidence rates of OA diagnoses of specific anatomic sites by occupational group warrant further analysis to examine adjusted (e.g., by age, sex, race/ethnicity) incidence rates among service members within occupational groups. Findings also suggest a need for additional research to identify military-specific equipment and activities that significantly increase risk of acute and chronic damage to joints (particularly, the knees, shoulder, and back). Results of such research would be useful to develop, test, and implement practical and effective countermeasures against OA and spondylosis among military members in general and those in high-risk occupations specifically.

References

- Loeser RF, Goldring SR, Scanzello CR, Goldring MB. Osteoarthritis: A disease of the joint as an organ. Arthritis Rheum. 202;64(6):1697–1707.

- Abramoff B, Caldera FE. Osteoarthritis: Pathology, diagnosis, and treatment options. Med Clin North Am. 2020;104(2):293–311.

- Hoff P, Buttgereit F, Burmester GR, Jakstadt M, Gaber T, Andreas K, et al. Osteoarthritis synovial fluid activates pro-inflammatory cytokines in primary human chondrocytes. Int Orthop. 2013;37(1):145–51.

- Liu-Bryan R, Terkeltaub R. Emerging regulators of the inflammatory process in osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2015;11(1):35–44.

- Maldonado M, Nam J. The Role of Changes in Extracellular Matrix of Cartilage in the Presence of Inflammation on the Pathology of Osteoarthritis. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:284873.

- Kraus VB, Blanco FJ, Englund M, Karsdal MA, Lohmander LS. Call for standardized definitions of osteoarthritis and risk stratification for clinical trials and clinical use. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2015;23(8):1233–1241.

- Knapik JJ, Pope R, Orr R, Schram B. Osteoarthritis: pathophysiology, prevalence, risk factors, and exercise for reducing pain and disability. J Spec Oper Med. 2018;18(3):94–102.

- Takagi I, Eliyas MJK, Stadlan N. Cervical spondylosis: An update on pathophysiology, clinical manifestation, and management strategies. Dis Mon. 2011;57(10)583–591.

- Theodore N. Degenerative cervical spondylosis. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(2):159–168.

- Change HJ, Lynm C, Glass RM. Osteoarthritis of the lumbar spine. JAMA. 2010;304(1):114.

- Johnson VL, Hunter DJ. The epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2014;28(1):5–15.

-

Srikanth VK, Fryer JL, Zhai G, et al. A meta-analysis of sex differences in prevalence, incidence, and severity of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2005;13(9):769–781.

-

Warner SC, Valdes AM. Genetic association studies in osteoarthritis: is it fairytale? Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2017;29(1):103–109.

-

Vina ER, Kwoh CK. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis: Literature update. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2018;30(2):160–167.

-

Neogi T, Zhang Y. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2013;39(1):1–19.

-

Cooper C, Inskip H, Croft P, et al. Individual risk factors for hip osteoarthritis: Obesity, hip injury and physical activity. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147(6):516– 522.

-

Spector TD, MacGregor AJ. Risk factors for osteoarthritis: genetics. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2004;12(S1):39–44.

-

Cooper C, Campbell L, Byng P, et al. Occupational activity and the risk of hip osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1996;55(9):680– 682.

-

Schouten JS, de Bie RA, Swaen G. An update on the relationship between occupational factors and osteoarthritis of the hip and knee. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2002;14(2):89–92.

-

Buckwalter JA, Lane NE. Athletics and osteoarthritis. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25(6):873–881.

-

Canetti EFD, Schram B, Orr RM, Knapik J, Pope R. Risk factors for development of lower limb osteoarthritis in physically demanding occupations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Appl Ergon. 2020;86:103097.

-

Schram B, Orr R, Pope R, Canetti, Knapik J. Risk factors for development of lower limb osteoarthritis in physically demanding occupations: A narrative umbrella review. J Occup Health. 2020;62(1):e12103.

-

Lohmander LS, Englund PM, Dahl LL, Roos EM. The long-term consequence of anterior cruciate ligament and meniscus injuries: osteoarthritis. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(10):1756–1769.

-

Englund M, Lohmander LS. Risk factors for symptomatic knee osteoarthritis fifteen to twenty-two years after meniscectomy. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(9):2811–2819.

-

Litwic A, Edwards MH, Dennison EM, Cooper C. Epidemiology and burden of osteoarthritis. Br Med Bull. 2013;105:185–199.

-

Felson DT, Zhang Y. An update on the epidemiology of knee and hip osteoarthritis with a view to prevention. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41(8):1343e55.

- Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part II. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(1):26e35.

- Hubertsson J, Petersson IF, Thorstensson CA, Englund M. Risk of sick leave and disability pension in working-age women and men with knee osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(3):401e5.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of doctor-diagnosed arthritis and arthritis-attributable activity limitation United States, 2010–2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(44):869–873.

- Showery JE, Kusnezov NA, Dunn JC, Bader JO, Belmont PJ Jr, Waterman BR. The rising incidence of degenerative and posttraumatic osteoarthritis of the knee in the United States military. J Arthroplasty. 2016 Mar. 21.

- Rivera JC, Wenke JC, Buckwalter JA, Ficke JR, Johnson AE. Posttraumatic osteoarthritis caused by battlefield injuries: the primary source of disability in warriors. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20(Suppl 1):S64–S69.

- Cross JD, Ficke JR, Hsu JR, et al. Battlefield orthopaedic injuries cause the majority of long-term disabilities. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011;19(Suppl 1):S1.

- Petilon J, Roth J, Hardenbrook M. Results of lumbar total disc arthroplasty in military personnel. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2011;24(5):297–301.

- Xie F, Kovic B, Jin X, et al. Economic and Humanistic Burden of Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review of Large Sample Studies. Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34:1087–1100.

-

United States Bone and Joint Initiative: The Burden of Musculoskeletal Diseases in the United States (BMUS), Fourth Edition. Rosemont, IL. Accessed 3 November 2021. https://www.boneandjointburden.org

-

Scher DL, Belmont PJ Jr, Mountcastle S, Owens BD. The incidence of primary hip osteoarthritis in active duty US military service members. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(4):468–475.

-

37. Kopec JA, Rahman MM, Berthelot JM, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of osteoarthritis in British Columbia, Canada. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(2):386–393.

-

Felson DT, Zhang Y, Hannan MT, et al. The incidence and natural history of knee osteoarthritis in the elderly: the Framingham Osteoarthritis Study. Arthritis Rheum 1995;38(10):1500–1505.

- Cameron KL, Hsiao MS, Owens BD, Burks R, Svoboda SJ. Incidence of physician-diagnosed osteoarthritis among active duty United States military service members. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(10):2974–2982.

- Dominick KL, Golightly YM, Jackson GL. Arthritis prevalence and symptoms among US non-veterans, veterans, and veterans receiving Department of Veterans Affairs healthcare. J Rheumatol. 2006;33(2):348–354.

- Rossignol M, Leclerc A, Hilliquin P, et al. Primary osteoarthritis and occupations: a national cross sectional survey of 10,412 symptomatic patients. Occup Environ Med. 2003;60(11):882–886.

- Feuerstein M, Berkowitz SM, Peck CA. Musculoskeletal-related disability in US Army personnel: prevalence, gender and military occupational specialties. J Occup Environ Med. 1997;39(1):68–78.

-

Cameron KL, Owens BD. The burden and management of sportsrelated musculoskeletal injuries and conditions within the US military. Clin Sports Med. 2014;33(4):573–589.

-

Patzkowski JC, Rivera JC, Ficke JR, Wenke JC. The changing face of disability in the US Army: the Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom effect. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20(Suppl 1):S23.

-

Rodriguez MJ, Garcia EJ, Dickens JF. Primary and posttraumatic knee osteoarthritis in the military. J Knee Surg. 2019;32(2):134–137.

-

Williams VF, Clark LL, Oh G. Update: Osteoarthritis and spondylosis, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2010–2015. MSMR. 2016;23(9):14–22.

-

Mehrotra A, Chernew M, Linetsky D, Hatch H, Cutler D, Schneider EC, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on outpatient care: visits return to prepandemic levels, but not for all providers and patients. 2020. Accessed 12 November 2021. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/2020/oct/impact-covid-19-pandemic-outpatient-care-visits-return-prepandemic-levels

-

Hacker KA, Briss PA, Richardson L, Wright J, Petersen R. COVID-19 and Chronic Disease: The Impact Now and in the Future. Prev Chronic Dis. 2021;18:E62.

-

Hartnett KP, Kite-Powell A, DeVies J, Coletta MA, Boehmer TK, Adjemian J, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on emergency department visits —United States, January 1, 2019–May 30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(23):699–704.

-

Czeisler MÉ, Marynak K, Clarke KEN, Salah Z, Shakya I, Thierry JM, et al. Delay or avoidance of medical care because of COVID-19–related concerns—United States, June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(36):1250–1257.

-

Nelson AE, Renner JB, Schwartz TA, Kraus VB, Helmick CG, Jordan JM. Differences in multi-joint radiographic osteoarthritis phenotypes among African Americans and Caucasians: The Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(12):3843–3852.

-

Nelson AE, Braga L, Renner JB, et al. Characterization of individual radiographic features of hip osteoarthritis in African American and white women and men: the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010;62(2):190–197.

-

Mazzuca SA, Brandt KD, Katz BP, Ding Y, Lane KA, Buckwalter. Risk factors for preogression of tibiofemoral osteoarthritis: An analysis based on fluoroscopically standardized knee radiography. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65(4):515–519.

-

Zhang Y, Jordan JM. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Clin Geriatr Med. 2010;26(3):355–369.

-

Petren-Mallmin M, Linder J. Cervical spine degeneration in fighter pilots and controls: a 5-yr follow-up study. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2001;72(5):443–446.

-

Aydog ST, Turbedar E, Demirel AH. Cervical and lumbar spinal changes diagnosed in four-view radiographs of 732 military pilots. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2004;75(2):154–157.

-

Byeon JH, Kim JW, Jeong HJ, et al. Degenerative changes of spine in helicopter pilots. Ann Rehabil Med. 2013;37(5):706–712.

-

Funakoshi M, Taoda K, Tsujimura H, Nishiyama K. Measurement of whole-body vibration in taxi drivers. J Occup Health. 2004;46(2):119–124.

-

Matsumoto Y, Griffin MJ. Non-linear characteristics in the dynamic responses of seated subjects exposed to vertical whole-body vibration. J Biomech Eng. 2002;124(5):527–532.

-

Sharp MA, Patton JF, Vogel JA. A Database of Physically Demanding Tasks Performed by U.S. Army Soldiers. Natick MA: Army Research Institute Of Environmental Medicine; 1998.

-

Berryman P, Lukes E, Aluoch MA, Wao HO. Risk factors for occupational osteoarthritis: a literature review. AAOHN J.2009;57(7):283–290.

-

Dulay GS, Cooper C, Dennison EM. Knee pain, knee injury, knee osteoarthritis & work. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2015;29(3):454–461.

-

Ezzat AM, Cibere J, Koehoorn M, Li LC. Association between cumulative joint loading from occupational activities and knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2013;65(10):1634–1642.

-

Jensen LK. Knee osteoarthritis: influence of work involving heavy lifting, kneeling, climbing stairs or ladders, or kneeling/squatting combined with heavy lifting. Occup Environ Med. 2008;65(2):72–89.

- Seidler A, Bolm-Audorff U, Abolmaali N, Elsner G, knee osteoarthritis study group. The role of cumulative physical work load in symptomatic knee osteoarthritis - a case-control study in Germany. J Occup Med Toxicol. 2008;3(1):14.

- Dahaghin S, Tehrani-Banihashemi SA, Faezi ST, Jamshidi AR, Davatchi F. Squatting, sitting on the floor, or cycling: are lifelong daily activities risk factors for clinical knee osteoarthritis? Stage III results of a community-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(10):1337–1342.

- Gignac MAM, Irvin E, Cullen K, et al. Mean and women’s occupational activities and the risk of developing osteoarthritis of the knee, hip, or hands: A systematic review and recommendations for future research. Arthritis Care Res. 2020;72(3):378–396.

-

Blagojevic M, Jinks C, Jeffery A, Jordan KP. Risk factors for onset of osteoarthritis of the knee in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18(1):24–33.

-

Pope R. Prediction and Prevention of Lower Limb Injuries and Attrition in Army Recruits. Bathurst, Australia: Charles Sturt University; 2002.

-

Cameron KL, Shing TL, Kardouni JR. The incidence of post-traumatic osteoarthritis in the knee in active duty military personnel compared to estimates in the general population. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017;25(S1):S184–S185.