Abstract

The Army Heat Center at Fort Benning, GA was established to identify and disseminate best practices for the prevention, field care, evacuation, hospital care, and return to duty of exertional heat casualties. During the 2017–2021 surveillance period, there were 1,911 heat casualties treated at Ft. Benning’s Martin Army Community Hospital. Most patients were junior enlisted and officer personnel who were engaged in initial entry training. Heat exhaustion, heat injury, heat stroke, and hyponatremia accounted for 52.6%, 18.4%, 18.2%, and 2.0% of total heat illnesses, respectively. The annual proportion of heat casualties that were due to heat exhaustion rose steadily during the surveillance period, reaching 77.7% in 2021, while the incidence of heat injury and heat stroke did not increase during this period. Data are presented on the occurrence of clusters of heat illness, the association of cases of heat stroke with arduous physical activities, and the seasonal variation in incidence of heat illnesses. It is important that unit leaders and trainers understand the risk factors for heat illness among those being trained and that early first aid measures be employed in the field (especially rapid cooling).

What are the new findings?

During the 5-year surveillance period, the emphasis on surveillance and prevention of heat illnesses at Ft. Benning has been associated with a reduction in the numbers of cases of the more severe types of heat illness (heat stroke and heat injury) and a simultaneous increase in the numbers of cases of heat exhaustion, a milder form of heat illness.

What is the impact on readiness and force health protection?

The added emphasis on surveillance and prevention of heat illness among service members whose duties involve strenuous physical exertion in a warm or hot environment can reduce the incidence and severity of heat illnesses in that population. Successful application of these force protection measures can contribute to the physical readiness of service members in both training and operational settings.

Background

Exertional heat illness (hereafter referred to as heat illness) spans a spectrum from relatively mild conditions such as heat cramps and heat exhaustion, to more serious and potentially life-threatening conditions such as heat injury and exertional heat stroke (hereafter heat stroke).1,2 As detailed elsewhere in this and in previous issues of the Medical Surveillance Monthly Report (MSMR), after peaking in 2018, the annual incidence rates for heat exhaustion and exertional heat stroke have declined in each of the subsequent years.3–5 These reports demonstrate that Fort Benning typically has the highest frequency of heat illnesses across the entire Department of Defense. Numerous risk factors for heat illnesses have been identified, including, but not limited to, environmental conditions, acclimatization status, aerobic fitness, body composition, age, sex, medication usage, tobacco use, mild illness, and individual effort/motivation.6–10 Knowledge of these and other risk factors, however, has done little to significantly reduce the incidence rate of heat illnesses during military training.

The Army Heat Center at Fort Benning was initially established as an ad hoc effort by Benning Martin Army Community Hospital (BMACH) clinicians in 2016, after the death of a trainee due to hyponatremia.11,12 In 2019, a sustainable approach to managing heat illnesses was established with the assignment of a research physiologist as Heat Center Director and funding for several support personnel. The mission of the Heat Center is to identify and disseminate best practices for the prevention, field care, evacuation, hospital care, and return to duty of exertional heat illness casualties. The Army Heat Center team aims to break the “tragedy loop.” This term refers to a cycle that begins with a tragic heat illness death that prompts a renewed focus on prevention, resulting in a short period of improvement in heat illness incidence. However, this reduction in incidence is followed by a subsequent heat illness death because of the reassignment of training personnel whose institutional memory of previous deaths is lost.12

A cornerstone of the Heat Center’s program is a detailed, accurate accounting of each heat illness casualty treated at BMACH, following the public health approach to injury prevention.13 In order to ensure complete and accurate data, each heat illness casualty is interviewed during a routine follow-up encounter with the BMACH Heat Center’s health care provider. These data are stored in the Exertional Heat Illness Repository, an IRB-approved data repository containing information on every heat illness casualty since 2017, with ongoing efforts to add earlier casualties. In addition to facilitating accurate diagnostic classification and reporting, the Heat Center team issues the initial limited duty profile, which guides the return to duty decision-making process. The purpose of the present study was to examine the characteristics of heat illnesses at Fort Benning, GA from 2017–2021 using data from the BMACH Heat Illness Repository, with special emphasis on annual trends, clusters of casualties, the type of activity being engaged in when heat illnesses occurred, and illness severity.

Methods

Data were obtained from the BMACH Exertional Heat Illness Repository (EIRB protocol #20-09914). The BMACH Human Protections Director reviewed the proposal specific to this project and determined that IRB review was not required for this retrospective review of existing, deidentified data. All heat casualties treated at BMACH from Jan 2017 through December 2021 were included in the analysis. Data elements extracted from the repository protocol included each casualty’s age, sex, unit of assignment, activity associated with the heat illness (e.g., foot march, run, physical readiness training), peak core temperature, diagnosis, mode of evacuation to BMACH, and dates of hospital admission and discharge. The diagnostic criteria used for heat exhaustion, heat injury, and exertional heat stroke are detailed in TB MED 507 Heat Stress Control and Heat Casualty Management.14 Minor heat-related illnesses (HRI) include diagnoses such as dehydration, heat syncope, and heat cramps. As of 2021, soldiers diagnosed with minor HRI were no longer directed for follow-up care at the Heat Clinic, therefore there are no reports of HRI in 2021. ICD-10 diagnosis codes for “other effects of heat and light” (ICD-10: T67.8) only appear in 2017 and likely represent improper coding of casualties, as the diagnostic criteria for this condition are ill-defined.

Clustering of cases was also assessed in this report. A cluster of heat illness casualties was defined as 4 or more on a given day. Once clusters were identified, the count by specific diagnosis and by unit (to the company-level) was determined. Denominator (unit size) data were not available for the calculation of incidence rates in this analysis.

Heat illness severity can be evaluated using several metrics. For this report, core (rectal) temperature (Tc) and the average and maximum length of hospitalization were examined. Core temperature (Tc) is measured via rectal thermistor by Emergency Medical Services (EMS) personnel upon arrival at the scene of a reported heat illness casualty.

Results

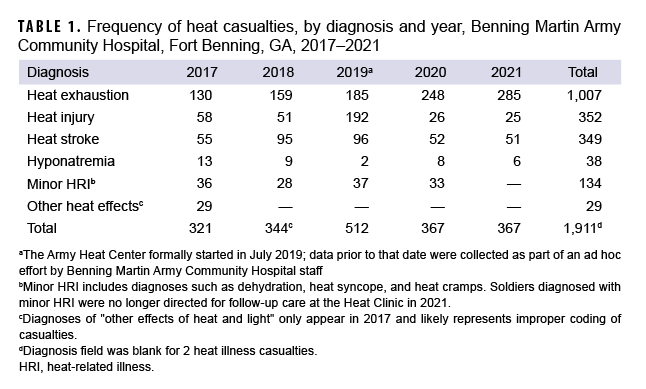

From 2017 through 2021, there were 1,911 total heat casualties treated at BMACH (Table 1). There were 1,703 men and 208 women in the cohort, which consisted primarily of junior enlisted (E1–E4; n=1,262) and company-grade-officer (O1–O3; n=288) soldiers. Similarly, the cohort consisted primarily of younger service members with a mean age of 22.3 years (SD=4.9 years); there were 7 heat illness casualties aged 40 or older, all of whom were cadre members as opposed to trainees (data not shown).

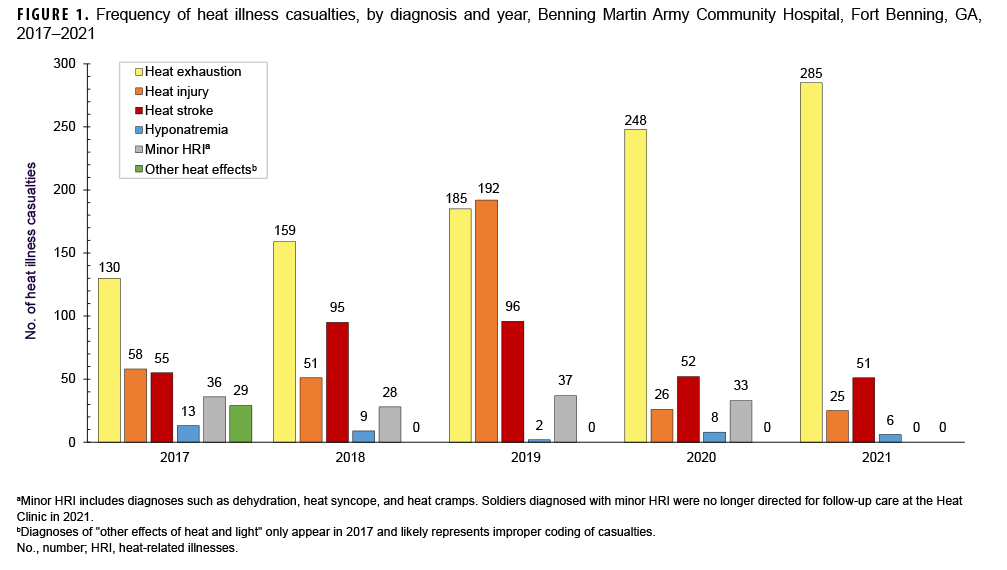

More than half (52.6%) of heat illness casualties documented during the 5-year period were heat exhaustion (n=1,007) (Table 1, Figure 1). Counts and relative proportions of heat exhaustion increased each year during the period; in 2021, heat exhaustion accounted for more than three-quarters (77.7%) of the total number of heat illness casualties. Heat injury, heat stroke, and hyponatremia accounted for 18.4%, 18.2%, and 2.0%, respectively, of total heat illnesses. There were 349 heat stroke casualties during the period. After peaking in 2018 (n=95) and 2019 (n=96), the number of heat stroke casualties was 46% lower in 2020 (n=52) and 2021 (n=51) (Table 1). Counts of heat injury casualties also decreased during the period; the number of hyponatremia cases remained relatively low throughout the period. Minor HRI casualties were reported from 2017 through 2020. No minor HRI casualties were recorded in 2021.

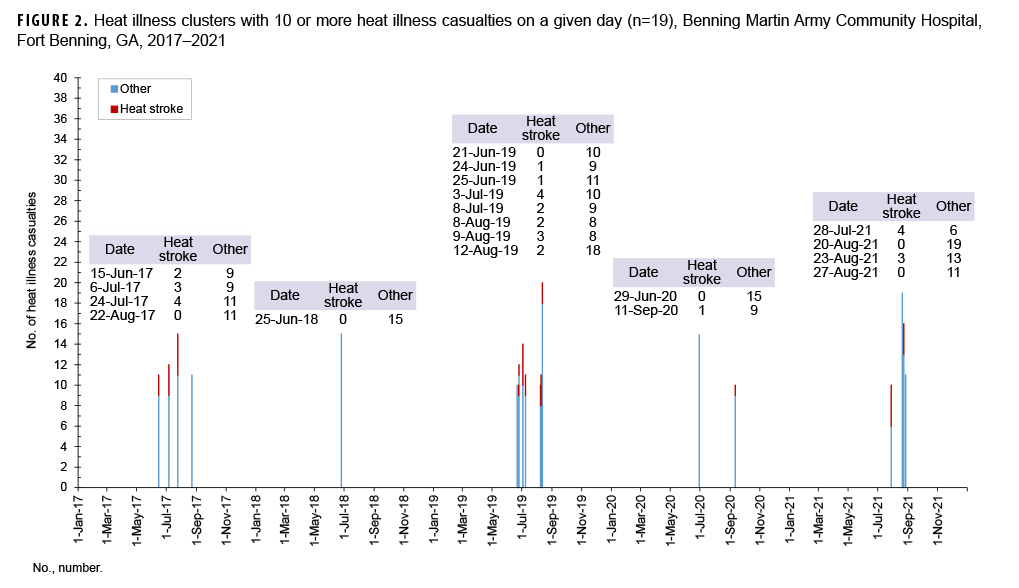

There were 178 days in which 4 or more heat illness casualties were reported. Clusters of 10 or more heat illness casualties occurred on 19 days during the surveillance period (Figure 2). The largest cluster consisted of 20 casualties, from 7 different companies (data not shown). The 19 clusters included 243 total heat illness casualties; among these, 32 (13.1%) were diagnosed with heat stroke (Figure 2). On days with multiple heat stroke casualties, casualties occurred across several training companies, such that there was only a single instance of 3 heat stroke casualties within a given company during the 5-year surveillance period (data not shown). Heat illness clusters occurred during the hottest months of each year, July through September.

Local Fort Benning policy states that EMS is the only authorized mode of evacuation to BMACH; in 2017, this metric was rarely noted in the Heat Illness Repository. From 2018 through 2020, 87.3%–88.6% of all suspected heat casualties were transported via EMS. In 2021, this proportion increased to 95.4%.

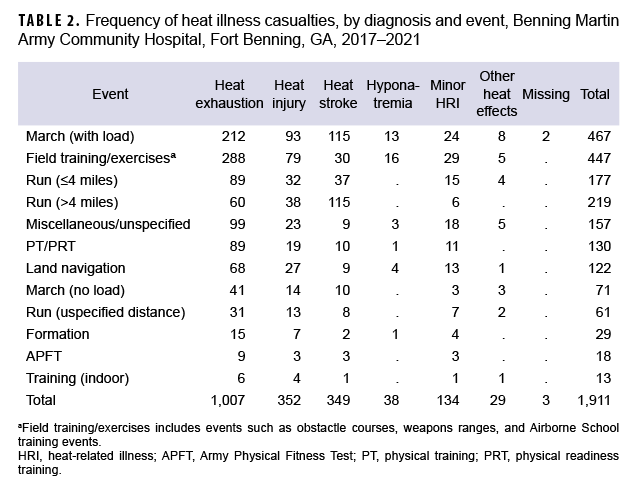

Frequency of heat illness casualties by diagnosis and type of activity showed that foot marches and running events accounted for more than four-fifths (81.7%) of all heat stroke casualties (Table 2). Specifically, marches with loads and runs greater than 4 miles accounted for about two-thirds (65.9%) of all heat stroke casualties. Field training/exercises, which includes a wide range of activities that do not fit into any of the other categories examined, was a predominant activity type for heat exhaustion, heat injury, and hyponatremia casualties.

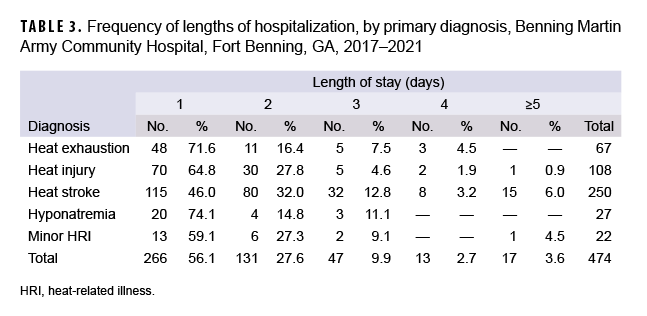

Seventy-five percent (75.2%; 1,437/1,911) of all heat illness casualties were treated and released the same day (i.e., not hospitalized) while 93.3% (940/1,007) of heat exhaustion casualties were treated and released the same day (Table 3). Of the heat illness casualties who were hospitalized, 83.8% had hospitalizations lasting 2 days or less (Table 3). Compared to other diagnoses, heat stroke accounted for the most hospitalizations (52.7%; n=250); however, most hospitalized heat stroke casualties (90.8%; n=227) had lengths of stay of 3 days or less. Twenty-three of the hospitalized heat stroke casualties had lengths of stay of 4 or more days and 6 had hospital stays longer than 1 week (the longest hospitalization lasted 2 weeks). During the study period, there was 1 fatality due to heat stroke.

Core temperature data were missing for 12.7% (n=242) of total heat illness casualties. In 2017, 22% of all casualties had Tc >40 °C (104.0 °F); however, by 2021 only 10% reported a Tc>40 °C (104.0 °F) (data not shown). Additionally, in 2017, 13 cases were profoundly hyperthermic, (Tc>42.0 °C [107.6 °F]) but no casualties exceeded this threshold in 2021.

Editorial Comment

There were several novel findings from this study. The severity of heat illness, specifically the number of heat stroke casualties, was the lowest since the formal creation of the Army Heat Center in July 2019. Clusters of heat illness casualties were infrequent, occurred during the hottest months of the year, and the predominant diagnosis during clusters was heat exhaustion. Clusters did not occur at the company level, but across battalions. Results indicated that clusters were generally due to weather conditions rather than to specific actions or inactions of individual units or companies. Furthermore, there were no clusters of heat stroke casualties during the surveillance period. Foot march and run events, particularly foot marches with load and runs of greater than 4 miles, were identified as events most frequently associated with heat stroke casualties. Finally, heat stroke casualties accounted for the most hospitalizations compared to other heat illnesses; however, most hospitalizations for heat stroke (78%) lasted no more than 1 to 2 days.

Because heat stroke casualties are at greatest risk of potential severe damage and mortality, each occurrence should be investigated. Despite the decrease in heat stroke counts during the study period, 1 death occurred and 4 heat stroke casualties were reported to have hospitalization lengths of stay greater than 9 days (likely due to prolonged end-organ damage, such as acute kidney injury, acute liver injury or exertional rhabdomyolysis). A significant proportion (81.7%) of heat stroke casualties occurred during run or foot march events. Local Fort Benning policy does not include these events in what are considered “high risk” activities for illness or injury, and therefore onsite medical coverage is not required for these events.

Given the potentially fatal nature of heat stroke and the requirement for rapid, aggressive cooling, the lack of medical coverage during run and foot march events is concerning.15–17 Results suggest that revision of local Fort Benning policy to categorize foot march and run events as high risk (particularly marches with load and run events greater than 4 miles) may be warranted. The presence of 68W combat medics during these events would augment the cadre’s ability to observe for and react to a suspected heat casualty, as well as improve response time and treatment. Non-medical personnel at Fort Benning are not permitted to obtain core temperature and rectal temperature is the only authorized method for assessing a suspected heat casualty. Additionally, cold water immersion is the gold standard for treatment of a heat stroke casualty; however, this method requires continuous core temperature monitoring in order to avoid over-cooling the casualty.18,19 Having medical personnel onsite, with continuous core temperature monitoring capability, would allow for increased utilization of cold water immersion for treatment and may result in improved outcomes.

Medical coverage during foot march and run events was a topic of discussion during the 2022 Fort Benning Heat Forum, held on 22 February. This event was attended by all Brigade- and Battalion-level leadership teams from across the installation. Additionally, the Fort Benning garrison safety office has since initiated a review of what are considered "high risk" events requiring onsite medical coverage, including foot march and run events.

There are several factors to consider when assessing the annual trends of heat illnesses during the surveillance period. The global COVID-19 pandemic presents a confounding influence on assessing annual trends in heat casualties during the study period as well as the impact of the Heat Center program. Heat acclimatization results in reduced thermal and cardiovascular strain, typically requires 7–14 days to fully develop, and is associated with reduced heat illness incidence.20,21 For much of 2020, a recently arrived enlisted recruit (the largest trainee population at Fort Benning) had a 14-day restriction of movement (ROM) period at the Reception Battalion. Once in-processing and the ROM period were completed, trainees without signs or symptoms of COVID-19 infection were permitted to ship to their training companies and start basic training. It has been speculated that during the ROM period, trainees who arrive from cooler environments become at least partially heat acclimatized and are subsequently at lower risk of becoming a heat illness casualties during the initial weeks of basic training. Early in the pandemic, temporary duty (TDY) travel to Fort Benning for certain schools was cancelled and the only individuals who could attend were those who were already present on the installation, such as recent graduates of initial entry training. During the summer of 2020, U.S. Army Ranger School did not experience a single exertional heat stroke casualty; there would typically have been 1–3 heat stroke casualties per Ranger School class during other summers during the surveillance period (data not shown). When TDY travel for Ranger School resumed with the September 2020 class, there were 3 heat stroke casualties, all of whom were in TDY status from a cooler and/or less humid home duty station. While it may be impractical for all trainees in a TDY status to arrive 2 weeks early to allow time for full heat acclimatization, it is important for trainees and unit leaders alike to understand the inherent heat illness risk for an unacclimatized trainee.

In addition to the impact of COVID-19 mitigation measures described above, other measures may also have influenced the trends in heat illness occurrence. While the wearing of a surgical mask has minimal impact on thermoregulatory responses to mild exercise in the heat, thermal sensation (one’s perception of how hot or cold they feel) can be negatively affected.22 Given the widespread wearing of face coverings during the pandemic and the subjective nature of heat exhaustion symptoms, such as generalized weakness, headache, fatigue, and lightheadedness,2,14 it may be difficult, if not impossible to quantify the impact of face coverings on the observed frequency of heat illnesses.

Caution is warranted when assessing annual changes in heat illness frequency other than those that are related to COVID-19. Prior to mid-2019, annotation of the details of each incident were accomplished with a team approach, in which numerous individuals contributed. With the formal establishment of the Heat Center, responsibilities were assigned, and standardized procedures were implemented. With the establishment of the Heat Clinic in early 2020, every heat casualty was seen by the Center’s Physician Assistant for their first follow-up encounter. During this office visit, additional details regarding the circumstances around the incident were obtained and any missing or conflicting information in the electronic medical record was reconciled.

Additionally, beginning the fall of 2020, standardized heat illness prevention, recognition and response training has been provided to all drill sergeants during their Brigade-level in-processing. A key message communicated during this training is that drill sergeants are encouraged to err on the side of caution and to activate EMS and initiating cooling measures if they suspect a trainee is a heat casualty. Given the subjective nature of many symptoms of heat exhaustion14 and considering that other more objective symptoms may resolve by the time the suspected casualty is evaluated in the Emergency Department, it is plausible that heat exhaustion is over-diagnosed. Heat Center staff have previously shown that as many as 30% of all heat illness casualties are incorrectly coded.23 While clinical staff have taken steps to correct this deficiency, it is possible that coding errors were more frequent during 2017–2019. The two-fold increase in heat exhaustion casualties during the surveillance period may be the result of improved recognition, over-diagnosis, and/or improved ICD-10 coding rather than a true increase in the number of heat exhaustion casualties. The dramatic increase in heat injury casualties in 2019 and subsequent drop in 2020 reinforce this point. Conversely, the increase in heat exhaustion may also be attributed to fewer casualties progressing in severity to heat stroke due to improvements described in this report (most notably, improved education, training, and surveillance).

There is an abundance of data demonstrating that the treatment priority for a suspected heat illness casualty is rapid, aggressive cooling.18,19 Drill sergeants and other cadre at Fort Benning are provided training on the ‘ice sheet’ protocol, the application of bed linens soaked in ice cold water to the suspected heat illness casualty. Fort Benning Maneuver Center of Excellence policy requires application of ice sheets and activation of EMS whenever a heat casualty is suspected by unit cadre. As a result, depending on the response time, the initial core temperature recorded by EMS is likely lower than the true peak, but may also be suggestive of improved responsiveness by unit cadre. Profound hyperthermia, defined as core temperature >42 °C (107.6 °F) is a predictor of poor prognosis.24,25 The reduction from 13 casualties which exceeded this threshold in 2017, down to 0 casualties in 2021 may reflect a combination of a positive impact of educational efforts, earlier recognition and response, improved utilization of the ice sheet protocol, or some combination of these factors. Regardless of the underlying cause, the lower frequency of extreme hyperthermia in recent years is interpreted as a positive trend that should be sustained.

The lack of denominator data for calculating incidence rates is a limitation of the current study. However, the size of the trainee and cadre populations at Fort Benning have remained relatively stable over the duration of the surveillance period. The exception is one station unit training (OSUT) for infantry and armor enlisted initial entry training, which expanded from 14 to 22 weeks in late 2019. As a result, since the expansion there are more initial entry trainees present at any one time, leading to a larger denominator for calculation of incidence rates. The observed decrease in the frequency of heat illnesses likely would have been confirmed had denominator data been available.

To some extent, heat illnesses are inevitable during military training in hot and/or humid environments, such as at Fort Benning, GA. Despite the efforts of leadership and cadre members, intrinsic and/or extrinsic motivational factors may inspire soldiers to exert themselves in such a way as to increase their risk of heat illness.20,25 During military training, soldiers are expected to physically test their limits and to pass minimum standards to progress to the next phase of training or to graduate from a course. Leaders must be aware that even when all reasonable preventive measures have been applied, the risk of a soldier becoming a heat injury casualty may remain elevated. In certain circumstances, it may be wise to instruct trainees that “just meeting the minimum” standard is enough and that a high heat risk day is not an appropriate opportunity to attempt to maximize one’s performance or to set a personal best time on an event.

In conclusion, data in this report demonstrate a general trend of decreasing severity and frequency of heat illness casualties at Fort Benning, GA during the surveillance period. While external factors beyond the influence of the Heat Center may have affected the trends, there is reason for cautious optimism that the education, training, and surveillance efforts have had a positive impact. Continued surveillance to confirm these trends and to identify future areas of improvement are warranted.

Author affiliations: Martin Army Community Hospital, Fort Benning, GA (LTC DeGroot and Ms. Henderson); Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, MD (Dr. O’Connor).

References

1. Leon LR, Bouchama A. Heat stroke. Compr Physiol. 2015;5(2):611–647.

2. Epstein Y, Yanovich R. Heatstroke. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(25):2449–2459.

3. Armed Forces Health Surveillance Division. Update: Heat illness, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2020. MSMR. 2021;28(4):10–15.

4. Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Update: Heat illness, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2019. MSMR. 2020;27(4):4–9.

5. Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Update: Heat illness, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2018. MSMR. 2019;26(4):15–20.

6. Nelson DA, Deuster PA, O'Connor FG, Kurina LM. Timing and Predictors of Mild and Severe Heat Illness among New Military Enlistees. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2018;50(8):1603–1612.

7. Westwood CS, Fallowfield JL, Delves SK, Nunns M, Ogden HB, Layden JD. Individual risk factors associated with exertional heat illness: A systematic review. Exp Physiol. 2020.

8. Alele FO, Malau-Aduli BS, Malau-Aduli AEO, M JC. Epidemiology of Exertional Heat Illness in the Military: A Systematic Review of Observational Studies. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(19):7037.

9. Carter R, III, Cheuvront SN, Williams JO, et al. Epidemiology of hospitalizations and deaths from heat illness in soldiers. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2005;37(8):1338–1344.

10. Gardner JW, Kark JA, Karnei K, et al. Risk factors predicting exertional heat illness in male Marine Corps recruits. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 1996;28(8):939–944.

11. DeGroot DW, O'Connor FG. Commentary: The Warrior Heat- and Exertion-Related Event Collaborative and the Fort Benning Heat Center. MSMR. 2020;27(4):2–3.

12. Galer M. The Heat Center Initiative. US Army Risk Management Quarterly. 2019;Spring:6–8.

13. Jones BH, Canham-Chervak M, Sleet DA. An evidence-based public health approach to injury priorities and prevention recommendations for the U.S. Military. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(1 Suppl):S1–10.

14. Headquarters, Department of the Army and Air Force. Technical Bulletin, Medical 507, Air Force Pamphlet 48-152. Heat Stress Control and Heat Casualty Management. 7 March 2003.

15. Belval LN, Casa DJ, Adams WM, et al. Consensus Statement- Prehospital Care of Exertional Heat Stroke. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2018;22(3):392–397.

16. Tustin AW, Cannon DL, Arbury SB, Thomas RJ, Hodgson MJ. Risk Factors for Heat-Related Illness in U.S. Workers: An OSHA Case Series. J Occup Environ Med. 2018;60(8):e383–e389.

17. Sithinamsuwan P, Piyavechviratana K, Kitthaweesin T, et al. Exertional heatstroke: early recognition and outcome with aggressive combined cooling--a 12-year experience. Mil Med. 2009;174(5):496–502.

18. Demartini JK, Casa DJ, Stearns R, et al. Effectiveness of cold water immersion in the treatment of exertional heat stroke at the Falmouth road race. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015;47(2):240–245.

19. Casa DJ, McDermott BP, Lee EC, Yeargin SW, Armstrong LE, Maresh CM. Cold water immersion: the gold standard for exertional heatstroke treatment. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2007;35(3):141–149.

20. Stacey MJ, Parsons IT, Woods DR, Taylor PN, Ross D, S JB. Susceptibility to exertional heat illness and hospitalisation risk in UK military personnel. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2015;1(1):e000055.

21. Sawka MN, Leon LR, Montain SJ, Sonna LA. Integrated Physiological Mechanisms of Exercise Performance, Adaptation, and Maladaptation to Heat Stress. Compr Physiol. 2011;1(4):1883–1928.

22. Kato I, Masuda Y, Nagashima K. Surgical masks do not increase the risk of heat stroke during mild exercise in hot and humid environment. Ind Health. 2021;59(5):325–333.

23. DeGroot DW, Mok G, Hathaway NE. International Classification of Disease Coding of Exertional Heat Illness in U.S. Army Soldiers. Mil Med. 2017;182(9):e1946–e1950.

24. Shibolet S, Coll R, Gilat T, Sohar E. Heatstroke: its clinical picture and mechanism in 36 cases. Q J Med. 1967;36(144):525–548.

25. Epstein Y, Druyan A, Heled Y. Heat injury prevention--a military perspective. J Strength Cond Res. 2012;26 Suppl 2:S82–86.