Plans for short, victorious wars often devolve into long conflicts of attrition. Isolated garrisons may suffer extraordinary casualties due to environmental injury, disease, and starvation if cut from supply lines. While Second World War Pacific conflicts clearly demonstrate, among both Allied and Axis troops, the harsh reality of force destruction caused by disease casualties, similar threats remain evident today.

The historical record of the U.S. Army in the Philippines and the 18th Imperial Japanese Army in New Guinea provide instructive examples of how such threats can change the course of a particular battle or an entire war. This Historical Perspective examines the medical consequences of 2 Pacific conflicts during the Second World War, with a focus on the effects of malaria. The current generation of medical officers must understand the harsh lessons of disease casualties caused by supply chain failures to ensure force health and readiness.

A major portion of this Historical Perspective was informed by reports of senior surviving Japanese officers. These men were set to work on a history of the war by their American captors during their detainment as possible war criminals. Their remarkable efforts were completed without the benefit of maps or operational orders, nearly all of which were lost or purposefully destroyed at the end of the war. U.S. military intelligence staff translated their reports into English, which were researched for this article. Morbidity and mortality estimates may differ with official U.S. histories of the war, but their figures were compiled with fewer resources over a shorter time. Most Japanese wanted to forget the war, especially their experiences in New Guinea, and commence rebuilding their country, resulting in a large historical gap unlikely ever to be filled.

U.S. Campaign in the Philippines

The Second World War in the Pacific began badly for the U.S. Forces. Soon after the December 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, isolated U.S. garrisons on islands throughout Southeast Asia fell to the Japanese offensive. Following the relocation of GEN MacArthur to Australia in March 1942, the largest mass surrender of U.S. forces occurred less than 2 months later at Bataan, during the loss of the Philippines to the Japanese Imperial Army. This defeat followed an uneven 5-month struggle distinguished by failure to reinforce or resupply Philippine island garrisons.3

Inadequate supplies of food and quinine led to starvation and epidemic malaria that plagued both sides of the Bataan campaign. In February 1942, the Japanese Imperial 14th Army had failed to break U.S. defensive lines, due in part to high rates of dysentery and malaria that sapped their personnel strength. The Japanese 14th had to be reinforced prior to resuming its offensive, with 50% to 60% of its soldiers incapacitated by malaria and 10% hospitalized for malaria treatment.4 It is likely that more than 1,000 of Japan’s 7,000 casualties were due to malaria.5 The U.S. Forces, comprised of approximately 23,000 U.S. and 100,000 Filipino soldiers, were on reduced rations from the beginning of the campaign, with quinine supplies sufficient only to suppress, but not prevent, near universal malaria infection.5

The April 1942 surrender of the starved and defeated 78,000 U.S. forces (66,000 Filipinos and 12,000 Americans) on Bataan and the subsequent surrender of the 10,000 Allied forces on Corregidor in May were the largest contingents ever to surrender in U.S. military history.3 At least 24,000 malaria patients, resulting from 500 to 700 new cases per day, were being treated at the time of surrender. What little microscopy that could be done suggested the ratio was 2:1 Plasmodium vivax to P falciparum.5

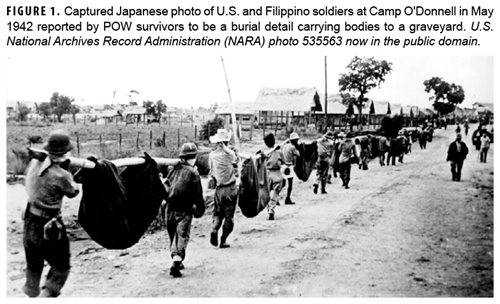

After fighting ended, the Allied prisoners were marched 55 miles to San Fernando on what was later known as the Bataan Death March. The situation worsened in Prisoner of War (POW) camps. Two thousand three hundred U.S. POWs were estimated to have died at Cabanatuan POW camp 1 during the latter half of 1942, with 25% of those deaths attributed to malaria. The highest monthly mortality figure was 789 deaths,6 in July 1942; the arrival of quinine tablets at Cabanatuan helped decrease total mortality by 500 in August. Filipino POW deaths in 1942 at Camp O’Donnell numbered 29,589, of which 6,129 (20.7%) were attributed to malaria; but the true count is likely much higher.6 Figure 1 shows what is thought to be a burial detail at Camp O’Donnell.

Although subsequent large military casualty events were mostly limited to the sinking of ships taking POWs from the Philippines to Japan, disease attrition continued among the POW population throughout the next 3 years. Ultimate cause of death was rarely a single event but a combination of events including malnutrition, especially of B vitamins (beriberi), trauma (skin ulcers), and infectious diseases, particularly bacillary dysentery and malaria.3,6 It is estimated that 37% of U.S. POWs did not survive the ordeal.7

Imperial Japanese Army Campaign in New Guinea

In the New Guinea campaign, GEN MacArthur’s strategy was one of envelopment: bypassing concentrations of enemy soldiers after neutralizing their abilities to interfere with the Allies’ extended supply lines.8-10 During their advance on the Philippines, multiple Imperial Japanese Army bases had been isolated and left to manage as best they could without rations, ammunition, or even communications from Japan. Despite extraordinary efforts to obtain tropical food sources, the isolated garrisons of the Japanese Imperial Army were gradually starved out of existence.11,12

Starvation and disease were 2 of the most significant contributors to the huge mortality suffered by Japanese forces. Rice ran out soon after the retreat from Madang, and essentially no supplies reached the 18th Japanese Army after mid-1944. The New Guinea jungle has few edible plants except the sago palm, which requires considerable labor to extract its protein-poor starch. Any animal protein that could be found was eaten by starving soldiers, including snakes and rats. Many men ate grass just to fill their stomachs. Unlike the 17th Japanese Army in Bougainville and New Britain, the 18th Army was never static enough for fixed agricultural production to any extent. Stories of cannibalism exist from the retreating line of soldiers from Lae to Madang to Wewak.13

Disease also dogged their footsteps, especially malaria, which was nearly universal due to the lack of any suppressive medications.14 Malaria killed more Japanese soldiers than battle injuries as the Allies took progressively larger offensive steps towards Japan.14 At one point in 1943, only 300 men of 1,700 in a Japanese infantry regiment were well enough to function as soldiers because the others were ill with malaria.4 Febrile malaria relapses consumed more calories, and sick men with fevers could not continue to march during the retreat. Many ended their lives with bullets or grenades rather than risk capture or an agonizing and slow death alone in the jungle.2,10,11,15  Many units lost 75% to 90% of their personnel, rendering them combat ineffective, as indicated by post-war 18th Japanese Army staff reports.2,15 Only 770 frontline infantry soldiers were estimated to have survived to the end of the war. One third of the survivors were ill enough to be hospitalized, and barely half the Army was capable of marching any distance.2,15 A 1,000-bed hospital constructed by the Japanese on Muschu Island received soldiers who had to be transported to their island prison by river barges (Figure 2). Despite medical supplies from the Australian Army, Japanese military medical officers struggled to maintain the health of their survivors on Muschu Island. Most Japanese officers and senior leaders had already died with their troops from battle injuries, malaria, or suicide.2,15

Many units lost 75% to 90% of their personnel, rendering them combat ineffective, as indicated by post-war 18th Japanese Army staff reports.2,15 Only 770 frontline infantry soldiers were estimated to have survived to the end of the war. One third of the survivors were ill enough to be hospitalized, and barely half the Army was capable of marching any distance.2,15 A 1,000-bed hospital constructed by the Japanese on Muschu Island received soldiers who had to be transported to their island prison by river barges (Figure 2). Despite medical supplies from the Australian Army, Japanese military medical officers struggled to maintain the health of their survivors on Muschu Island. Most Japanese officers and senior leaders had already died with their troops from battle injuries, malaria, or suicide.2,15

Conclusion

The catastrophic casualties incurred from the failure of supply lines during these battles provide an important lesson for future conflicts. Modern warfare is more dependent than ever on functioning supply lines to keep soldiers fed and equipped. Starving soldiers will suffer low morale and decreased will to fight, as will those with febrile diseases. The importance of prevention, for both disease and non-battle injuries, remains as critical to military success today as it was nearly a century ago.

Author Affiliations

Australian Defence Force Infectious Disease and Malaria Institute, Gallipoli Barracks, Enoggera, Queensland, Australia and the University of Queensland, School of Public Health, Brisbane, Herston, Queensland, Australia (Dr. Dennis Shanks).

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges the service and sacrifice of all those who served in the military during the Second World War and thanks the many unnamed military officers, scientists, historians, and medical librarians who have unselfishly provided data and ideas for this manuscript, especially the librarians at the Australian Defence Force Library at Gallipoli Barracks, Queensland.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Australian Defence Force or the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. The author does not claim any conflicts of interest. No specific funding was given for this work.

References

- Milner S. Victory in Papua: United States Army in World War II—The War in the Pacific. Office of the Chief of Military History, Dept. of the Army; 1957.

- Yoshihara T. Southern cross: Japanese eastern New Guinea campaign. Australian War Memorial 54. 1955. Accessed December 1, 2021. https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C2759564

- Morton L. The Fall of the Philippines: United States Army in World War II—The War in the Pacific. Office of the Chief of Military History, Dept. of the Army; 1953.

- Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, Allied Translator and Interpreter Section. Research Report: Survey of Japanese Medical Units. National Library of Medicine. 1947. Accessed December 1, 2021. https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-14210390R-bk

- Gillespie JO. Malaria and the defence of Bataan. In: Coates JB, ed. Communicable Diseases: Malaria—Preventive Medicine in World War II. Vol. 6. Office of the Surgeon General, Dept. of the Army; 1963.

- Cooper WE, U.S. Army Medical Department. Medical Department Activities in the Philippines for 1941 to 6 May 1942, and Including Medical Activities in Japanese Prisoner of War Camps. National Library of Medicine. 1946. Accessed December 1, 2021. https://resource.nlm.nih.gov/14120230R

- Klein RE, Wells MR, Somers JM. American Prisoners of War (POWs) and Missing in Action (MIAs). Office of the Assistant Secretary for Policy, Planning, and Preparedness (OPP&P), U.S. Dept. of Veterans Affairs; 2006:10.

- Miller J. Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul: United States Army in World War II—The War in the Pacific. Office of the Chief of Military History, Dept. of the Army; 1959.

- Smith RR. The Approach to the Philippines: United States Army in World War II—The War in the Pacific. Office of the Chief of Military History, Dept. of the Army; 1953.

- Spector RH. Eagle Against the Sun: The American War with Japan. Simon and Schuster, Inc.; 2012.

- Cook HT, Cook TF. Japan at War: An Oral History. The New Press; 1993.

- Harries M, Harries S. Soldiers of the Sun: The Rise and Fall of the Imperial Japanese Army. Random House; 1991.

- Morris N. Japanese War Crimes in the Pacific: Australia’s Investigations and Prosecutions—Research Guide. National Archives of Australia. 2019. Accessed December 1, 2021. https://www.naa.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-06/research-guide-japanese-war-crimes-in-the-pacific_0.pdf

- Bullard S. ‘The great enemy of humanity’: malaria and the Japanese medical corps in Papua, 1942-43. J Pac Hist. 2004;39(2):203-220.

- Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, Allied Translator and Interpreter Section; Military History Section, U.S. Army Forces East Headquarters. 18th Army Operations: Japanese Monographs—Japanese Studies in World War II. Vol. 5. Office of the Chief of Military History, U.S. Dept. of the Army; 1945.

EDITORIAL COMMENT

Disease and Non-Battle Injury as a Driving Force for Improved Medical Readiness

Shanks highlights supply issues and poor logistics as proximate causes of disease and non-battle injuries (DNBI). Throughout military history, DNBIs have accounted for large numbers of casualties. The U.S. military’s proportion of deaths from DNBI versus battle injuries fell from approximately 60% during the Civil War to 20% in the Vietnam War.1

Even in the more limited Iraq campaign in the early phases of Operation Iraqi Freedom (March 2003-April 2005), non-battle injuries were triple the number injured due to enemy action.2 Reliable reports from the ongoing Russia-Ukraine conflict are difficult to verify, but the lay press has reported significant challenges posed by environmental extremes.3 Even with well-supplied forces and limited engagements, environmental and disease planning remain critical to force readiness and mission success.

After observing the devastating effects of malaria, especially in the South Pacific, the U.S. military was instrumental in the research and development of effective anti-malarial medications. Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (WRAIR) took on this challenge and, building on the earlier work of German researchers,4 developed and synthesized the first effective anti-malarial, chloroquine, by the end of the Second World War. WRAIR remains at the forefront of anti-malarial development, executing a critical role in the development and approval of key anti-malaria medications including primaquine, mefloquine, doxycycline, atovaquone/proguanil, tafenoquine, and artesunate.4,5,6

References

- Withers BG, Craig SC. The historical impact of preventive medicine in war. In: Kelley PW, ed. Military Preventive Medicine: Mobilization and Deployment. Vol. 1. Borden Institute, Walter Reed Army Medical Center; 2003:21-57.

- Zouris JM, Wade AL, Mango, CP. Injury and illness casualty distributions among U.S. Army and Marine Corps personnel during Operation Iraqi Freedom. Mil Med. 2008; 173(3):247-252.

- MacDonald A. Ukraine’s winter could turn against Russian troops. Wall Street Journal. January 21, 2023. Accessed February 22, 2023. https://www.wsj.com/articles/ukraines-winter-could-turn-against-russian-troops-11674294354.

- Belete TM. Recent progress in the development of new antimalarial drugs with novel targets. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2020;14:3875-3889.

- U.S. Military HIV Research Program (MHRP). Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (WRAIR). Accessed February 21, 2023. https://www.hivresearch.org/about-us/wrair.

- Zottig VE, Shanks GD. The evolution of post-exposure prohylaxis for vivax malaria since the Korean War. MSMR. 2021;28(2):8-10.

![]()