Background

Infertility, defined as the inability to achieve a successful pregnancy after 1 year or more of unprotected sexual intercourse or therapeutic donor insemination, affects approximately 15% of all couples.1–3 Male infertility is diagnosed when, after testing both partners, reproductive problems have been found in the male.1 A male factor contributes in part or whole to about 50% of cases of infertility.4–6 However, determining the true prevalence of male infertility remains elusive, as most estimates are derived from couples seeking assistive reproductive technology in tertiary care or referral centers, population-based surveys, or high-risk occupational cohorts, all of which are likely to underestimate the prevalence of the condition in the general U.S. population.2,7–12

Infertility in men is typically evaluated using semen analysis to assess sperm concentration, motility, and morphology. The most common causes of male infertility are low sperm production, abnormal sperm function, or problems that affect sperm transport.10 However, the cause of male infertility is unknown (idiopathic male infertility) in up to 40% of cases,7,10 and while many infertile men have oligospermia (low sperm concentrations compared with reference ranges) or azoospermia (the absence of motile sperm in semen), some infertile men have normal sperm concentrations.7 Illness, infection, injury, chronic medical conditions, hormonal disorders, genetic disorders, and lifestyle choices (e.g., heavy alcohol use, smoking, or illicit drug use) also may contribute to male infertility.13 In addition, frequent exposure to certain environmental elements such as high temperatures, toxins, medications, and radiation can adversely affect sperm production and/or sperm function.13

The current report updates and expands on the findings of the previous MSMR analysis of infertility among active component service men.14 Specifically, the current report summarizes the frequencies, rates, temporal trends, types of infertility, and demographic and military characteristics of infertility among active component service men during 2013–2017.

Methods

The surveillance period was 1 Jan. 2013 through 31 Dec. 2017. The surveillance population consisted of active component service members of the U.S. Army, Navy, Air Force, or Marine Corps who served at any time during the surveillance period. Diagnoses were ascertained from administrative records of all medical encounters of individuals who received care in fixed (i.e., not deployed or at sea) medical facilities of the Military Health System (MHS) or civilian facilities in the Click to closePurchased CareThe TRICARE Health Program is often referred to as purchased care. It is the services we “purchase” through the managed care support contracts.purchased care system. These data are maintained in the electronic database of the Defense Medical Surveillance System (DMSS).

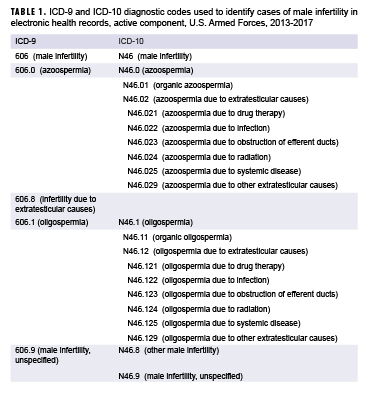

For surveillance purposes, an incident case of male infertility was defined by a case-defining diagnosis (Table 1) in the first diagnostic position of a record of an inpatient or outpatient medical encounter.15 These cases were then grouped into 5 types of male infertility based on the ICD coding system: male infertility unspecified, azoospermia, oligospermia, other male infertility, and infertility due to extratesticular causes. Infertility due to extratesticular causes (ICD-9) was considered a type of male infertility during 2013–2015 only. Other male infertility was considered a type during 2015–2017 only.

The incidence date was considered the date of the first hospitalization or outpatient medical encounter that included a case-defining diagnosis of male infertility. An individual could be counted as an incident case of male infertility only once during the surveillance period; service men with a documented diagnosis of infertility prior to the surveillance period were excluded from the analysis. Incidence rates were calculated as incident male infertility diagnoses per 10,000 person-years (p-yrs) and were stratified by infertility type as well as by demographic and military characteristics. To assess the health care burden associated with male infertility, medical encounters were analyzed separately. The number of inpatient or outpatient encounters with a case-defining diagnostic code recorded in the primary position and the total number of unique individuals affected were computed for each calendar year in the surveillance period.

Results

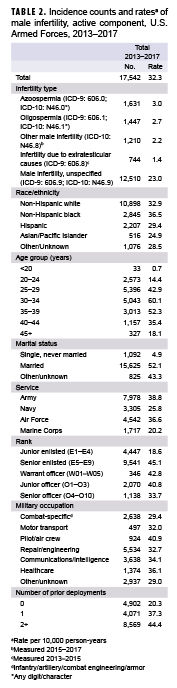

During the 5-year surveillance period, a total of 17,542 active component service men received incident diagnoses of male infertility, for a crude overall incidence rate of 32.3 cases per 10,000 p-yrs (Table 2). The majority of incident male infertility cases were unspecified male infertility (71.3%), followed by azoospermia (9.3%), oligospermia (8.2%), other male infertility (6.9%), and infertility due to extratesticular causes (4.2%). Azoospermia (3.0 per 10,000 p-yrs) and oligospermia (2.7 per 10,000 p-yrs) were diagnosed at much lower rates than male infertility, unspecified (23.0 per 10,000 p-yrs).

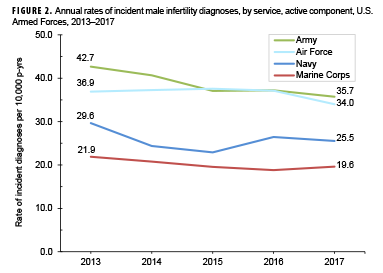

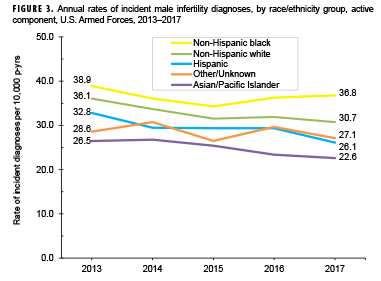

Compared to their respective counterparts, crude overall rates of incident infertility diagnoses were highest among service men aged 30–34 years (60.1 per 10,000 p-yrs), non-Hispanic blacks (36.5 per 10,000 p-yrs), those who were married (52.1 per 10,000 p-yrs), senior enlisted service men (45.1 per 10,000 p-yrs), those working as pilots/air crew (40.9 per 10,000 p-yrs), and those who had 2 or more prior deployments (44.4 per 10,000 p-yrs). Across the services, overall rates of male infertility diagnoses were highest among Army (38.8 per 10,000 p-yrs) or Air Force members (36.6 per 10,000 p-yrs) and lowest among Marine Corps members (20.2 per 10,000 p-yrs) (Table 2).

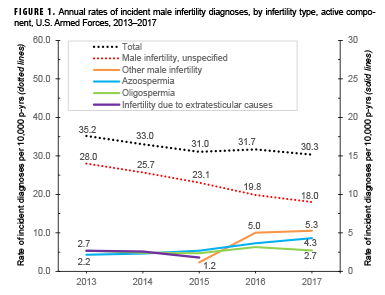

Annual rates of incident diagnoses of total male infertility decreased slightly from 35.2 per 10,000 p-yrs in 2013 to 30.3 per 10,000 p-yrs in 2017 (Figure 1). Rates of diagnoses of male infertility, unspecified showed a steady decrease (35.7%) over the course of the 5-year period from 28.0 per 10,000 p-yrs in 2013 to 18.0 per 10,000 p-yrs in 2017. Annual rates of incident azoospermia diagnoses increased from 2.2 per 10,000 p-yrs in 2013 to 4.3 per 10,000 p-yrs in 2017, while annual rates of incident oligospermia diagnoses were relatively stable during the period. Annual incidence rates of other male infertility diagnoses (ICD-10 only) increased markedly, rising from 1.2 per 10,000 p-yrs in 2015 (first year of use of this diagnostic code) to 5.3 per 10,000 p-yrs in 2017. Annual rates of infertility due to extratesticular causes (ICD-9 only) remained relatively low and stable during 2013–2015 (Figure 1).

Stratification of annual incidence rates of male infertility diagnoses by age group showed that rates among service men aged 30–34 years were consistently higher than rates among those in other age groups (data not shown). During the 5-year surveillance period, annual rates of incident diagnoses of male infertility decreased in each service (Figure 2). During each year of the period, incidence rates of male infertility diagnoses were highest among Army and Air Force members. Annual rates of male infertility diagnoses were intermediate among Navy members and lowest among Marine Corps members. However, compared to their respective counterparts, service men in the Army showed the greatest decrease (16.3%) in male infertility rates over time. Decreases over time in annual rates of incident male infertility diagnoses were seen in all race/ethnicity groups; Hispanic service men showed the greatest decrease over time and those of other/unknown race/ethnicity and non-Hispanic black service men showed the smallest decreases (Figure 3).

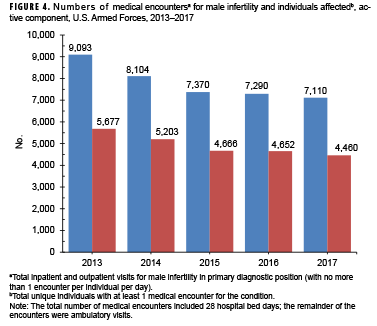

From 2013 through 2017, annual numbers of medical encounters during which male infertility was recorded as a primary (first-listed) diagnosis decreased 21.8% between 2013 and 2017 (Figure 4). Because there was a comparable decrease (21.4%) in the number of individuals affected, the ratio of medical encounters per individual affected remained steady at 1.6 throughout the surveillance period.

Editorial Comments

Annual rates of incident diagnoses of total male infertility among active component service men decreased slightly during 2013–2017. The overall trend in annual rates closely reflected and was primarily influenced by the trend in incident diagnoses of unspecified male infertility. Data on trends in the incidence of male infertility in the general U.S. population during a comparable time period were not available at the time of this report, precluding comparisons to the current results.

Similar to the findings of the 2014 MSMR analysis of incident diagnoses of male infertility among active component service men during 2000–2012, annual rates were consistently higher among service men aged 30–34 years compared to those in other age groups.14 The overall rate of incident diagnoses of male infertility was also highest among non-Hispanic black service men, which is consistent with the findings of the prior MSMR analysis.14 U.S. data on male factor infertility by race/ethnicity are limited in the current literature. In age-adjusted analyses of data from U.S. veterans, Hispanic men had the highest frequency of treatment for male infertility, followed by non-Hispanic black men and non-Hispanic white men.16 However, a 2001 retrospective study using a centralized database of patient records at a single military male infertility clinic found that race did not appear to be a significant factor influencing the prevalence of male infertility (i.e., the racial background of the study population mirrored that of all MHS beneficiaries).17 More recently, in samples of U.S. men seeking infertility evaluation and/or treatment, non-Hispanic blacks were found to have lower mean semen volume, sperm concentration, total sperm count, and total motile sperm than non-Hispanic whites or Hispanics.18–21

In the current analysis, azoospermia accounted for 9.3% of the incident diagnoses of infertility. This finding is similar to prior literature, which found that 10–15% of all infertile men produce semen devoid of viable sperm.22–24

The results presented here must be interpreted in light of several important limitations. First, to the extent that some affected service men did not seek care for infertility or sought care outside of the MHS, the counts and rates reported here underestimate the actual counts and rates of male infertility in the active component of the U.S. Armed Forces. Another limitation of the current analysis is related to the implementation of MHS GENESIS, the new electronic health record for the MHS. For 2017, medical data from sites that were using MHS GENESIS are not available in DMSS. These sites include Naval Hospital Oak Harbor, Naval Hospital Bremerton, Air Force Medical Services Fairchild, and Madigan Army Medical Center. Therefore, medical encounter data for individuals seeking care at any of these facilities during 2017 were not included in the analysis. Finally, because incident cases were identified based on the presence of a qualifying ICD-9 or ICD-10 diagnosis code for male infertility recorded during a health care encounter, the validity of the results depends upon the accuracy of a physician-assigned diagnosis of male infertility and the resultant diagnostic coding generated by a given encounter. However, a recent claims-based study of 11,068 male patients at a single U.S. institution to assess whether ICD-9 codes accurately identified men with abnormal semen analyses25 found that the specificity of diagnostic coding for azoospermia, oligospermia, infertility due to extratesticular causes, and unspecified male infertility were all greater than 90%. However, sensitivity was not calculated, as not all patients had a documented semen analysis.26

References

- Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Definitions of infertility and recurrent pregnancy loss: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2013;99(1):63.

- Thonneau P, Marchand S, Tallec A, et al. Incidence and main causes of infertility in a resident population (1,850,000) of three French regions (1988-1989). Hum Reprod. 1991;6(6):811–816.

- Thoma ME, McLain AC, Louis JF, et al. Prevalence of infertility in the United States as estimated by the current duration approach and a traditional constructed approach. Fertil Steril. 2013;99(5):1324–1331.

- Dupree JM. Insurance coverage for male infertility care in the United States. Asian J Androl. 2016;18(3):339–341.

- Hull MG, Glazener CM, Kelly NJ, et al. Population study of causes, treatment, and outcome of infertility. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1985;291(6510):1693–1697.

- Mehta A, Nangia AK, Dupree JM, Smith JF. Limitations and barriers in access to care for male factor infertility. Fertil Steril. 2016;105(5):1128–1137.

- Jungwirth A, Giwercman A, Tournaye H, et al. European Association of Urology guidelines on male infertility: the 2012 update. Eur Urol. 2012;62(2):324–332.

- Agarwal A, Mulgund A, Hamada A, Chyatte MR. A unique view on male infertility around the globe. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2015;13:37.

- Martinez G, Daniels K, Chandra A. Fertility of men and women aged 15–44 years in the United States: National Survey of Family Growth, 2006–2010. Natl Health Stat Report. 2012;(51):1–28.

-

1Winters BR, Walsh TJ. The epidemiology of male infertility. Urol Clin North Am. 2014;41(1):195–204.

- Alavanja MC, Sandler DP, McMaster SB, et al. The Agricultural Health Study. Environ Health Perspect. 1996;104(4):362–369.

- Sallmen M, Sandler DP, Hoppin JA, Blair A, Baird DD. Reduced fertility among overweight and obese men. Epidemiology. 2006;17(5):520–523.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reproductive Health. Infertility FAQs. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/infertility/. Accessed 28 Feb. 2019. Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center. Surveillance snapshot: male infertility, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2000–2012. MSMR. 2014;21(2):13.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Surveillance Case Definitions. Male Infertility. https://health.mil/Military-Health-Topics/Combat-Support/Armed-Forces-Health-Surveillance-Branch/Epidemiology-and-Analysis/Surveillance-Case-Definitions. Accessed 28 Feb. 2019.

- Meacham RB, Joyce GF, Wise M, Kparker A, Niederberger C. Urologic Diseases in America Project. Male infertility. J Urol. 2007;177(6):2058–2066.

- Costabile RA, Spevak M. Characterization of patients presenting with male factor infertility in an equal access, no cost medical system. Urology. 2001;58(6):1021–1024.

- Redmon JB, Thomas W, Ma W, et al. Semen parameters in fertile US men: the Study for Future Families. Andrology. 2013;1(6):806–814.

- Povey AC, Clyma JA, McNamee R, et al. Modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors for poor semen quality: a case-referent study. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(9):2799–2806.

- Walsh TF, Feigenbaum SL, Smith JF, Croughan MS, VanDenEeden SK. Epidemiologic characteristics of men evaluated for infertility in a large, pre-paid insurance plan. Fertil Steril. 2008;90(suppl):S63.

-

Khandwala YS, Zhang CA, Li S, Behr B, Guo D, Eisenberg ML. Racial variation in semen quality at fertility evaluation. Urology. 2017;106:96–102.

-

Eisenberg ML, Lathi RB, Baker VL, Westphal LM, Milki AA, Nangia AK. Frequency of the male infertility evaluation: data from the National Survey of Family Growth. J Urol. 2013;189(3):1030–1034.

-

Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine in collaboration with Society for Male Reproduction and Urology. Evaluation of the azoospermic male. Fertil Steril. 2008;90:S74–S77.

-

Gudeloglu A, Parekattil SJ. Update in the evaluation of the azoospermic male. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2013;68(suppl 1):27–34.

-

World Health Organization. WHO Laboratory Manual for the examination of human semen and sperm-cervical mucus interaction. 4th ed. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1999.

- Khandwala YS, Zhang CA, Li S, Cullen MR, Eisenberg ML. Validity of claims data for the identification of male infertility. Curr Urol Rep. 2017;18(9):68.