What Are the New Findings?

The crude overall incidence rate of FND diagnoses among U.S. active component service members during 2000-2018 was 29.5 per 100,000 p-yrs, which is approximately 2.5-7.4 times higher than estimates reported for the general U.S. population. The overall rates of FND among service members with a history of depression or a history of PTSD were more than 10 times the rates among individuals without such a history.

What Is the Impact on Readiness and Force Health Protection?

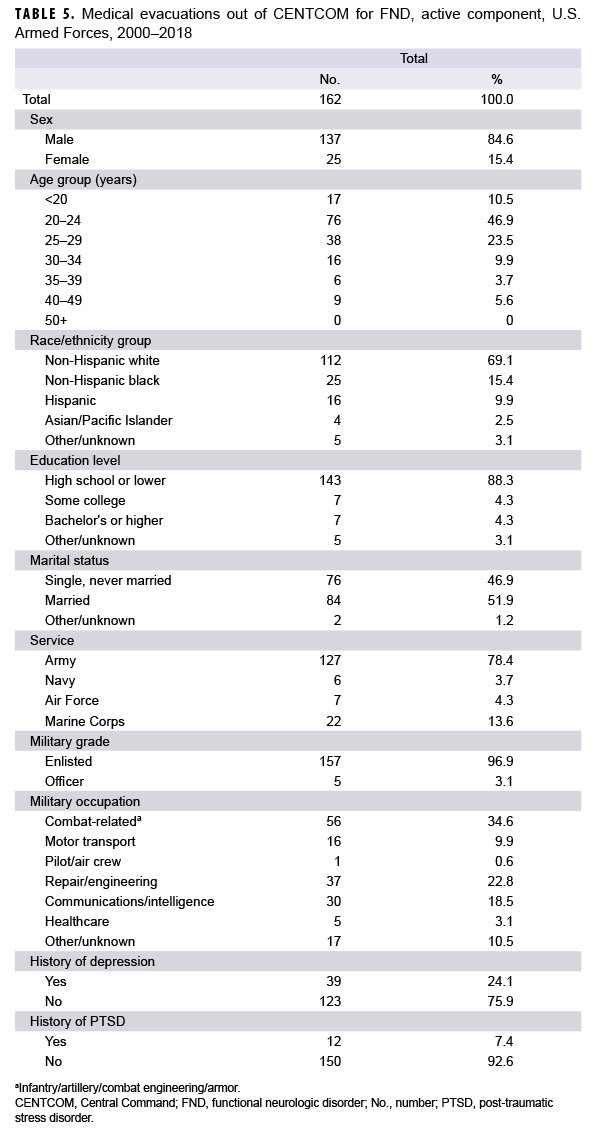

There was a total of 162 medical evacuations out of CENTCOM for FND during the study period. Additional data exploring the impact of FND diagnosis on readiness and force health protection are warranted.

Abstract

Functional neurological disorder (FND) is a complex neuropsychiatric disorder characterized by abnormal or atypical sensorimotor, gait, dissociative, or special sensory symptoms in the absence of structural nervous system lesions to explain the symptoms. Several factors are thought to be associated with FND, including comorbid mental health conditions; exposure to physical, emotional, or sexual trauma; young age, and low socioeconomic status. U.S. military service members may be at increased risk for FND because of the prevalence of some of these factors. The current study evaluated the incidence of FND in the U.S. Armed Forces between 2000 and 2018. The overall incidence rate was 29.5 per 100,000 person-years (p-yrs), with the highest rates among women and individuals less than 20 years old. The overall median annual prevalence rate was 37.2 per 100,000 persons. In addition, there were 162 medical evacuations out of the Central Command (CENTCOM) area of responsibility for FND during the study period. Most medical evacuations occurred among men and those with no history of depression or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Background

Functional neurological disorder (FND) is a complex neuropsychiatric disorder characterized by abnormal or atypical sensorimotor, gait, dissociative, or special sensory symptoms in the absence of structural nervous system lesions to explain the symptoms. As such, the symptoms of FND are inconsistent with currently understood central nervous system pathophysiology.1 Other terms like "hysteria," "functional neurologic symptom disorder," "psychogenic disorder," and "conversion disorder" have historically been used in the diagnosis of FND, highlighting both the methodological heterogeneity and etiologic uncertainty that are characteristic of this disorder.2 Methodological and clinical barriers have been recognized as limitations to the study of FND and are likely leading contributors to the under diagnosis of the condition.3 However, recent increasing awareness of this disorder has led to advances in the understanding of the epidemiology and pathophysiology of this complex condition.4

The estimated incidence rate of FND in the general population is 0.4-1.2 per 10,000 person-years (p-yrs),1,3,5 and 1.1-2.2 per 10,000 p-yrs in psychiatric settings.6 FND can present in all age groups, including children.7-9 The diagnosis is most common among women and more common among patients with a history of childhood abuse of any kind, including emotional, physical, and sexual abuse.3 There is also evidence that the prevalence of FND may be higher among individuals with lower educational achievement, lower socioeconomic status, and in underdeveloped countries.10,11 Race is not thought to be a significant independent contributing factor in the diagnosis of FND.11

Comorbid psychiatric illness has been widely recognized as a major risk factor for FND. Studies have consistently found that patients with FND are diagnosed more frequently with depression and have higher levels of depressive symptoms.12 The same has been observed with anxiety.3 A recent study comparing the association of depression and anxiety symptoms found that depression may be more predictive of functional symptoms, regardless of the severity of anxiety.13 Notwithstanding, whether functional symptoms are a consequence of or risk factor for depression or anxiety remains unclear. Functional neurological symptoms have been observed in other non psychiatric clinical populations as well, including inpatient, outpatient, and obstetric settings.11,14

Exposure to trauma, particularly combat trauma from military conflict, has been associated with the development of FND throughout history.15,16 Review of individual cases from the American Civil War suggests that FND was probably highly prevalent among soldiers, particularly among those diagnosed with epilepsy or paralysis.17 Historical data from the U.S. Army reported an estimated incidence of FND of 15.3 per 10,000 p-yrs at the end of World War I.18 The occurrence of the condition among British, French, and German forces was also written about extensively after World War I.19 Academic interest in FND waned after World War II, but the condition was believed to be less common during this period than during World War I. There was a continual decline in incidence estimates following World War II, with increases again during the Korea and Vietnam conflicts. The incidence of FND in the Korea-Vietnam era reached a peak in 1975 at 9.5 cases per 10,000 p-yrs and has been slowly declining since that time based on 1991 estimates.15

Conditions associated with FND, including depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), are prevalent among current members of the U.S. Armed Forces.20 However, because of the potential adverse occupational, financial, and emotional impacts of this condition,11 it remains a potentially important unexplored area of study. The current study assessed the epidemiology of FND among active component service members by first describing the incidence and prevalence of FND between 2000 and 2018 as well as the time between FND diagnosis and medical separation. To quantify the impact of FND on operational deployments, the number of FND-related medical evacuations out of the Central Command (CENTCOM) area of responsibility (AOR) was also described.

Methods

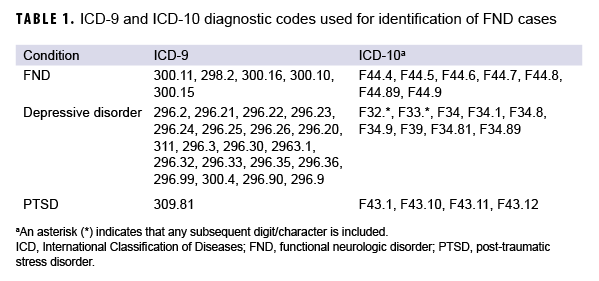

The surveillance period was 1 Jan. 2000 through 31 Dec. 2018. The surveillance population consisted of all active component service members of the U.S. Army, Navy, Air Force, or Marine Corps who served at any time during the period. All data used for the analysis were ascertained from the Defense Medical Surveillance System. Diagnoses were ascertained from 1) administrative records of all medical encounters of individuals who received care in fixed (i.e., not deployed or at sea) medical facilities of the Military Health System or in civilian facilities in the Click to closePurchased CareThe TRICARE Health Program is often referred to as purchased care. It is the services we “purchase” through the managed care support contracts.purchased care system and 2) in-theater medical records contained in the Theater Medical Data Store. Records of all medical evacuations conducted by the U.S. Transportation Command (TRANSCOM) and maintained in the TRANSCOM Regulating and Command and Control Evacuation System were used as the source of evacuation data. Deployment data were ascertained from the Defense Manpower Data Center Contingency Tracking System deployment roster. However, at the time of this analysis, deployment data were unavailable for the Navy and Marine Corps; therefore, deployment data for members of these services were supplemented with information collected using the post-deployment health assessment form (DD2796).

An incident case of FND was defined by records having 1) an inpatient encounter with a qualifying diagnosis (Table 1) in any diagnostic position, 2) an outpatient encounter with a qualifying diagnosis in any diagnostic position made in a neurology or mental health clinic (Medical Expense and Performance Reporting System code beginning with BAK or BF, respectively), or 3) at least 2 outpatient or in-theater medical encounters within 90 days of each other, with the qualifying diagnosis in any diagnostic position. The incidence date was defined as the date of the first case-defining encounter. Inpatient encounters were prioritized over outpatient and in-theater medical encounters if multiple encounters occurred on the same incident date. An individual could count as an incident case once per lifetime. Prevalent cases (i.e., cases occurring before the start of the surveillance period) and their corresponding person-time were excluded from the incidence rate calculations. Incidence rates were calculated per 100,000 p-yrs. In addition, the number of incident cases that occurred within 1 year before military separation were identified.

A prevalent case of FND in any given year was defined as someone who met criteria for becoming an incident case any time on or before the end of the surveillance period and had an inpatient, outpatient, or in-theater medical encounter with a qualifying diagnosis in any diagnostic position during the given calendar year. The encounter also had to occur on or after the incident case diagnosis date. For prevalence calculations, the denominator was the number of service members who were in service during June of the given calendar year.

Medical evacuations for FND were also identified. Medical evacuations were included in the analysis if the evacuated service member was evacuated from the CENTCOM AOR to a medical treatment facility outside the CENTCOM AOR and if the service member had at least 1 outpatient or inpatient medical encounter with a diagnosis of FND in the first or second diagnostic position during the time period from 5 days before to 10 days after the reported evacuation date.

Covariates used in the analysis included age, sex, race/ethnicity group, service branch, marital status, education level, grade, occupation, deployment history, history of depression, and history of PTSD. Deployment history was defined by having ever deployed in support of Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF), Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF), or Operation New Dawn (OND). History of depression and history of PTSD were defined by ever having been diagnosed as an incident case of depression or PTSD. This meant having an inpatient encounter with a qualifying diagnosis (Table 1) in the first or second diagnostic position, an outpatient encounter with a qualifying diagnosis in the first or second diagnostic position made in a mental health specialty clinic, or at least 2 outpatient or in-theater medical encounters within 180 days of each other with a qualifying diagnosis in the first or second diagnostic position, occurring before the FND diagnosis.

Results

Incidence

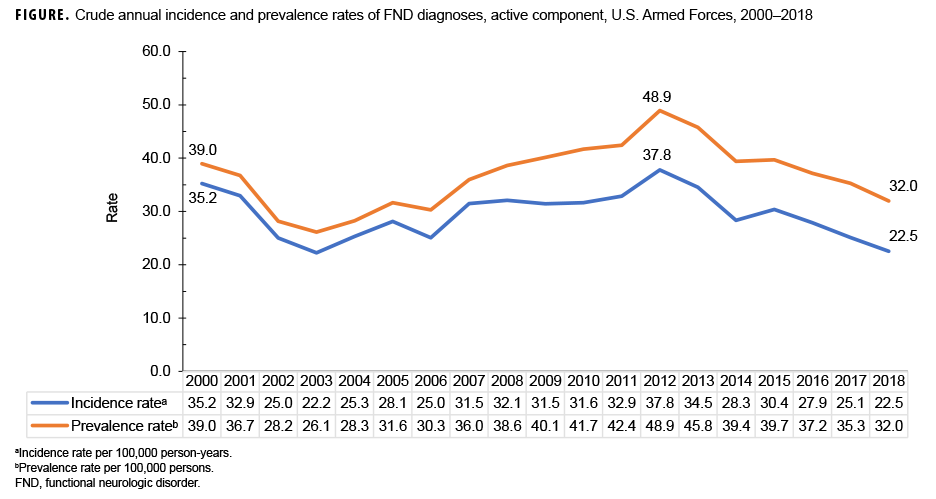

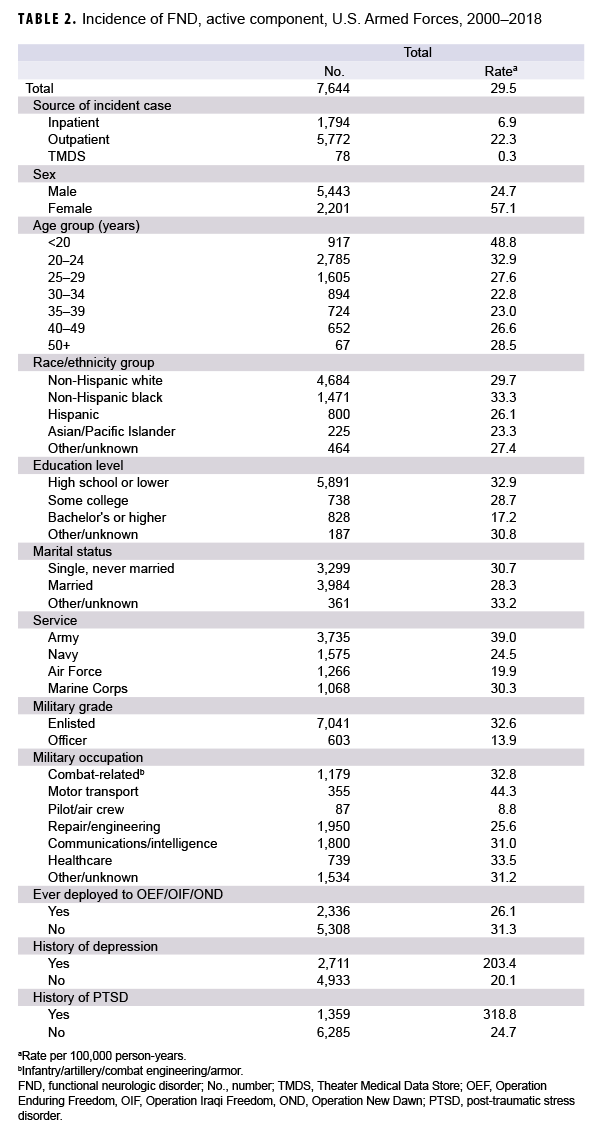

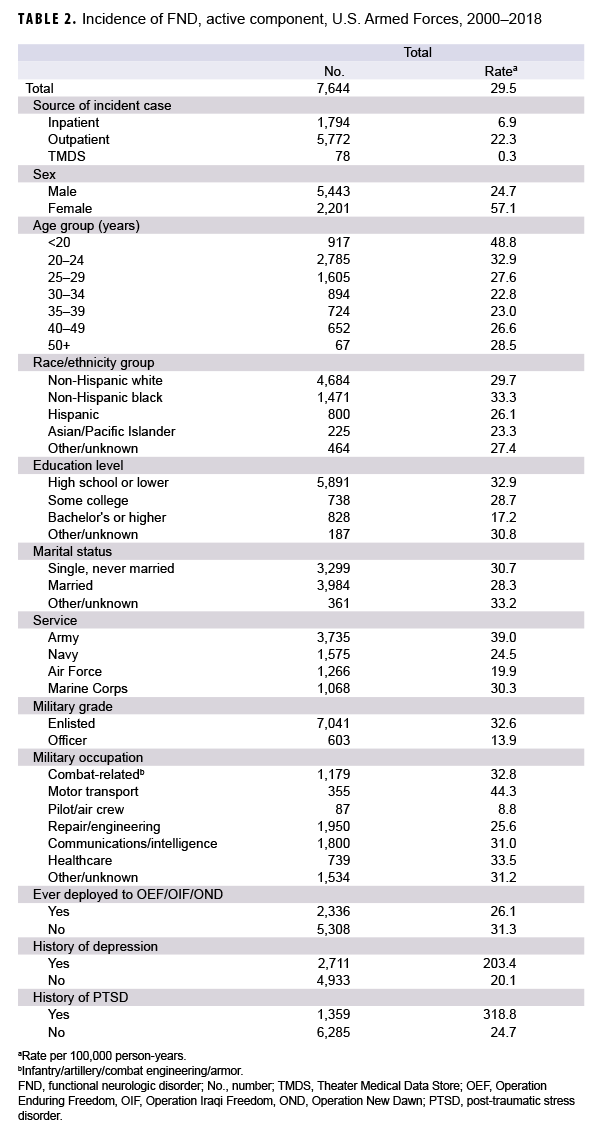

During 2000-2018, there were 7,644 incident cases of FND among active component service members, with a crude overall incidence rate of 29.5 cases per 100,000 p-yrs (Table 2). The crude annual incidence rate of FND diagnoses was highest in 2012 (37.8 per 100,000 p-yrs) and lowest in 2003 (22.2 per 100,000 p-yrs) (Figure 1). The overall incidence rate among females was 2.3 times that of males (57.1 and 24.7 per 100,000 p-yrs, respectively) (Table 2). Overall rates of incident FND diagnoses were highest among individuals younger than 20 years of age (48.8 per 100,000 p-yrs) and lowest among individuals 30-34 years of age (22.8 per 100,000 p-yrs). Overall rates were highest among non-Hispanic blacks (33.3 per 100,000 p-yrs) and lowest among Asian/Pacific Islanders (23.3 per 100,000 p-yrs). Rates were highest among those with other/unknown marital status (which includes divorced and widowed) and lowest among married individuals (33.2 vs 28.3 per 100,000 p-yrs, respectively). Incidence rates of FND diagnoses were highest among individuals with lower levels of education (high school or lower) and lowest among individuals with a bachelor's degree or higher education (32.9 vs 17.2 per 100,000 p-yrs, respectively). The overall rate among service members with a history of depression was 10.1 times that of those without such a history (203.4 vs 20.1 per 100,000 p-yrs, respectively). Similarly, the overall rate among individuals with a history of PTSD was 12.9 times that of those without such a history (318.8 vs 24.7 per 100,000 p-yrs, respectively).

Among the service branches, overall rates of incident FND diagnoses were highest among those in the Army (39.0 per 100,000 p-yrs) and lowest among those in the Air Force (19.9 per 100,000 p-yrs) (Table 2). The rate among enlisted individuals was 2.3 times the rate among officers (32.6 vs 13.9 per 100,000 p-yrs, respectively). Overall rates were highest among motor transport crew and lowest among pilot/air crew (44.3 vs 8.8 per 100,000 p-yrs, respectively). Finally, rates were higher among those who never deployed to OEF/OIF/OND compared to those who had deployed (31.3 vs 26.1 per 100,000 p-yrs, respectively).

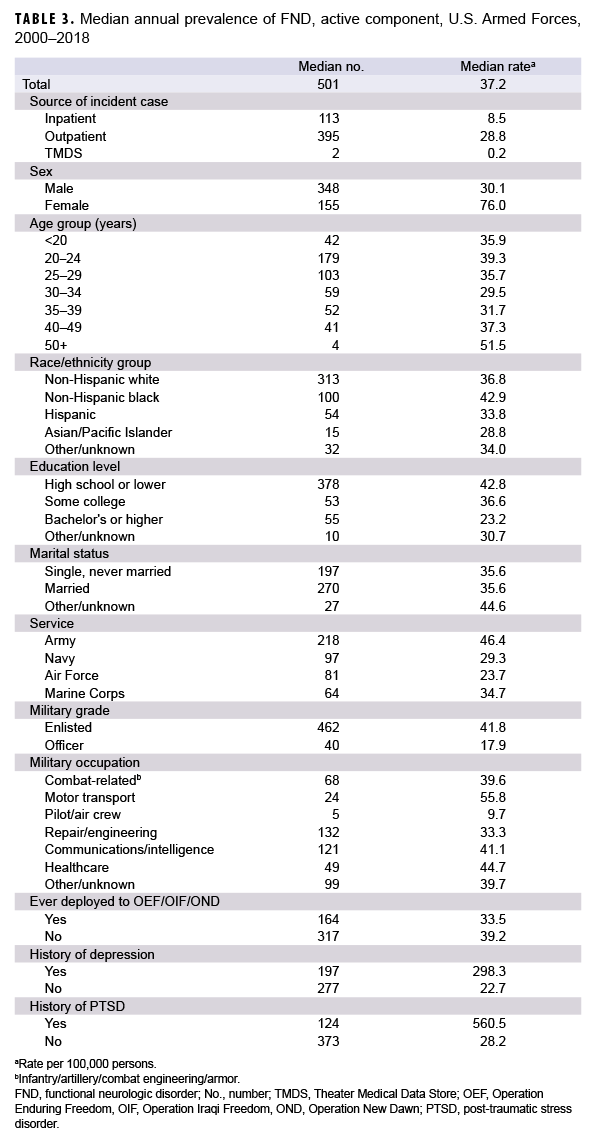

Prevalence

The overall median annual prevalence rate of FND diagnoses during the study period was 37.2 cases per 100,000 persons (Table 3). The annual trend in prevalence rates generally mirrored that of the annual trend in incidence rates (Figure 1). In addition, patterns of prevalence followed similar demographic distributions as the patterns of incidence (Table 3). Overall prevalence rates of FND diagnoses were higher among women compared to men (76.0 vs 30.1 per 100,000 persons, respectively). In addition, prevalence rates were highest among non-Hispanic black individuals, those with other/unknown marital status, enlisted service members, those with lower levels of education, Army members, and those working in motor transport. A notable exception to the incidence rate trends was age; the highest prevalence was among individuals age 50 and older (51.5 per 100,000 persons). Finally, prevalence rates were again higher among those who had no deployment history to OEF/OIF/OND compared to those who did (39.2 vs 33.5 per 100,000 persons), those with a history of depression compared to those without (298.3 vs 22.7 per 100,000 persons), and those with a history of PTSD compared to those without (560.5 vs 28.2 per 100,000 persons).

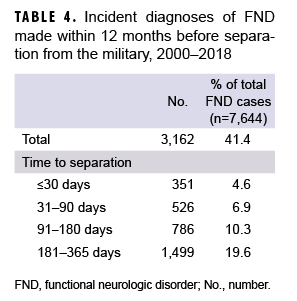

Military separation

A total of 3,162 cases of FND were diagnosed within 1 year before military separation, accounting for 41.4% of total FND cases (Table 4). Only 4.6% (n=351) of cases were diagnosed within 30 days or fewer before separation. The majority (4,482; 58.6%) of active component service members diagnosed with FND remained on active duty for longer than 365 days after their incident diagnoses

Medical evacuation

There were 162 medical evacuations out of CENTCOM for FND during the study period (Table 5). A majority of medical evacuees for FND were male (84.6%) and 24 years old or younger (57.4%). Most medical evacuations occurred among non- Hispanic white service members (69.1%), Army service members (78.4%), those with a lower level of education (88.3%), those with a combat-related occupational specialty (34.6%), and those with an enlisted military grade (96.9%) compared to their respective counterparts. Slightly more than half of those evacuated for FND were married (51.9%), and greater majorities had no history of depression (75.9%) or PTSD (92.6%) (Table 5).

Editorial Comment

This study found a crude overall rate of incident FND diagnoses of 29.5 per 100,000 p-yrs, which is approximately 2.5-7.4 times higher than estimates reported for the general population.1,3,5 Similar to other studies, incidence rates were highest among women, younger age groups, and individuals with lower levels of education. Interestingly, incidence of FND was lowest among the 30-34 year old age group with a gradual increase thereafter, suggestive of a bimodal distribution of incidence rates. Prevalence rates were highest among service members aged 50 years or older; however, during this period, there were generally very few prevalent cases of FND in this age group (median of prevalent cases per year=4).

The finding that the overall incidence of FND diagnoses was highest among those with the lowest educational attainment supports previous observations.10,11 However, this association is likely confounded by age since FND incidence was also highest among the youngest service members. Similar to other studies, there were no clear differences in FND incidence rates among the various race/ethnicity groups.11 Finally, rates among divorced and widowed individuals were higher compared to married individuals, though this difference was small.

Several previous studies have observed an association of FND with comorbid psychiatric conditions, including depressive disorders and PTSD.3 Findings from the current study support this widely observed finding, noting that the overall incidence rates among individuals with a history of depression or PTSD were more than 10 times the rates of those without histories of these conditions and approximately 13 times higher among individuals with a history of PTSD compared to those without. It is unknown whether FND represents an adverse outcome of these conditions or a risk factor for them. Future studies may help to better characterize this relationship.

The overall incidence and prevalence rates of FND diagnoses were highest among individuals in the motor transport primary occupational specialty. A previous study conducted among U.S. Armed Forces found that incidence rates of traumatic brain injury among those working in armor/motor transport were second only to those in combat-specific occupations.21 The relationship of these conditions to both mechanical and emotional trauma related to training exercises, routine occupational duty, improvised explosive device blast exposure, or other factors is unclear and was not assessed in this study. Rates were lowest among pilots/air crew. This finding has been observed in other studies and may be due to reluctance to seek medical care for conditions that can limit flight status.22

There were 162 medical evacuations out of CENTCOM for FND during the study period. By contrast, there were 1,264 medical evacuations for all causes from theater in 2018 alone, and there were more medical evacuations for mental health disorders (n=356; 28.2%) than for any other diagnosis category that year.23 Mental health disorders, which include FND, have consistently been among the most commonly represented diagnostic categories for medical evacuation over the past several years.24-27 While there are typically higher ratios of females to males for mental health medical evacuation, data from the present study demonstrated a higher ratio of male to female evacuations for FND. Future studies may be needed to examine the association between medical evacuations for conditions in certain broad diagnostic categories (e.g., mental health disorders; signs, symptoms, and ill-defined conditions; nervous system and sense organs) and a subsequent diagnosis of FND.

The crude overall rate of incident FND diagnoses was lower among individuals who had previously deployed to OEF/OIF/ OND compared to that of individuals who had not. One explanation for this difference in overall incidence rates could be the "healthy deployer effect," in which service members who are diagnosed with deployment- limiting conditions are prevented from being deployed. These deployment limiting conditions include psychiatric disorders that impair duty performance and mental health conditions that pose a substantial risk for deterioration. Because the development of functional symptoms has been related to poor resilience and coping strategies during times of stress,28,29 future studies may help to better define and identify these qualities in service members to potentially avoid the development of functional symptoms during periods of increased stress.

There are several limitations to this study. Because FND is probably under-diagnosed,3 the data reported here are likely an underestimate of the true burden of these conditions. In particular, the use of administrative data to capture prevalent cases of FND likely results in an underestimate of the true prevalence since service members were only captured as being a prevalent case if they sought care for FND during the given calendar year. The case definition used to identify incident cases of FND in this study likely reduced the possibility of capturing provider miscoded diagnoses of FND since the case definition excluded cases in which only a single outpatient diagnosis was made, which is a strength. However, it is also possible that this resulted in the exclusion of some true cases of FND.

This study did not adjust for any confounders such as history of adverse childhood events, which have been recognized as a risk factor for the development of FND.3,30 As mentioned, exposure to specific combat-related stressors, interpersonal stressors, and other occupational stressors related to deployment were not assessed. Prospective cohort studies may be better suited to more adequately characterize the relative impacts that each of these factors has on the development of FND in the deployed setting. Finally, additional research exploring the impact of FND on medical readiness, mission accomplishment, and financial burden to the military is also warranted and may be the focus of future projects.

Author affiliations: Department of Neurology, Naval Medical Center San Diego, San Diego, CA (LT Garrett, LCDR Hodges), Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch, Silver Spring, MD (Dr. Stahlman).

References

- Feinstein A. Conversion disorder. Continuum (Mineap Minn). 2018;24(3):861-872.

-

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

-

Carson AJ, Brown R, David AS, et al. Functional (conversion) neurological symptoms: research since the millennium. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83(8):842-850.

-

Thenganatt MA, Jankovic J. Psychogenic (functional) movement disorders. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2019;25(4):1121-1140.

- Stone J, Warlow C, Sharpe M. The symptom of functional weakness: a controlled study of 107 patients. Brain. 2010;133(Pt 5):1537-1551.

- Stefánsson JG, Messina JA, Meyerowitz S. Hysterical neurosis, conversion type: clinical and epidemiological considerations. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1976;53(2):119-138.

- Ferrara J, Jankovic J. Psychogenic movement disorders in children. Mov Disord Off J Mov Disord Soc. 2008;23(13):1875-1881.

- Harris SR. Psychogenic movement disorders in children and adolescents: an update. Eur J Pediatr. 2019;178(4):581-585.

- Teo W, Choong C-T. Neurological presentations of conversion disorders in a group of Singapore children. Pediatr Int. 2008;50(4):533-536.

- Owens C, Dein S. Conversion disorder: the modern hysteria. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2006;12(2):152-157.

- Ali S, Jabeen S, Pate RJ, et al. Conversion disorder—mind versus body: a review. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2015;12(5-6):27-33.

- Khan MNS, Ahmad S, Arshad N, Ullah N, Maqsood N. Anxiety and depressive symptoms in patients with conversion disorder. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2005;15(8):489-492.

-

Yilmaz S, Bilgiç A, Akça ÖF, Türkoglu S, Hergüner S. Relationships among depression, anxiety, anxiety sensitivity, and perceived social support in adolescents with conversion disorder. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2016;20(1):10-18.

-

Diaz Allegue M, Gonzales Bardanca S, Pato Lopez O, Abeledo Fernandez MA, Rama Maceiras Maceiras P. Epidural anesthesia in labor and conversion disorder. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim. 2009;56(5):312-314.

- Weinstein EA. Conversion disorders. In: Zajtchuk R, Bellamy RF, eds. Textbook of Military Medicine. War Psychiatry. Falls Church, VA: Office of the Surgeon General; 1995:383-407.

-

Trimble M, Reynolds EH. A brief history of hysteria: from the ancient to the modern. Handb Clin Neurol. 2016;139:3-10.

-

Barnes JK. The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion (1861-1865). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 1870.

-

Bailey P, Haber R. Chapter 8: Occurrence of Neuropsychiatric Disease in the Army. In: The Medical Department of United States Army in the World War. Volume 10: Neuropsychiatry. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1929:154.

-

Babinski JHF, Froment, J. Hysteria or Pithiatism and Reflex Nervous Disorders in the Neurology of War. London: University of London Press; 1918.

-

Stahlman S, Oetting AA. Mental health disorders and mental health problems, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2007-2016. MSMR. 2018;25(3):2-11.

-

Williams VF, Stahlman S, Hunt DJ, O’Donnell FL. Diagnoses of traumatic brain injury not clearly associated with deployment, U.S. Armed Forces, 2001-2016. MSMR. 2017;24(3):2-8.

- Garrett AR, Bazaco SL, Clausen SS, Oetting AA, Stahlman S. Epidemiology of impulse control disorders and association with dopamine agonist exposure, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2014-2018. MSMR. 2019;26(8):10-16.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Medical evacuations out of the U.S. Central Command, active and reserve components, U.S. Armed Forces, 2018. MSMR. 2019;26(5):28-33.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Update: Medical evacuations, active and reserve components, U.S. Armed Forces, 2017. MSMR. 2018;25(7):17-22.

- Williams VF, Stahlman S, Oh G-T. Medical evacuations, active and reserve components, U.S. Armed Forces, 2013-2015. MSMR. 2017;24(2):15-21.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Medical evacuations from Afghanistan during Operation Enduring Freedom, active and reserve components, U.S. Armed Forces, 7 Oct. 2001- 31 Dec. 2012. MSMR. 2013;20(6):2-8.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Medical evacuations from Operation Iraqi Freedom/ Operation New Dawn, active and reserve components, U.S. Armed Forces, 2003-2011. MSMR. 2012;19(2):18-21.

- Fischer S, Lemmer G, Gollwitzer M, Nater UM. Stress and resilience in functional somatic syndromes —a structural equation modeling approach. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e111214.

- Jalilianhasanpour R, Williams B, Gilman I, et al. Resilience linked to personality dimensions, alexithymia and affective symptoms in motor functional neurological disorders. J Psychosom Res. 2018;107:55-61.

- Nicholson TR, Aybek S, Craig T, et al. Life events and escape in conversion disorder. Psychol Med. 2016;46(12):2617-2626.