What Are the New Findings?

The crude overall incidence rate of unspecified gastroenteritis/diarrhea among active component service members during 2010– 2019 was more than 75 times the combined overall rates of acute GI infections attributable to the 5 specific pathogens of interest. Annual rates of unspecified gastroenteritis/diarrhea and all pathogen-specific GI infections except Shigella increased over the course of the 10-year period.

What Is the Impact On Readiness and Force Health Protection?

Unspecified gastroenteritis and diarrheal illnesses remain prevalent among military personnel and can significantly degrade service members readiness for duty. Increased diagnostic testing of nonspecific acute GI infections is warranted to further elucidate which GI pathogens are the most prevalent in this population.

Abstract

Laboratory, reportable medical event, and medical encounter data were analyzed to identify incident cases of acute gastrointestinal (GI) infections caused by Campylobacter, nontyphoidal Salmonella, Shigella, Escherichia coli (E. coli), or norovirus as well as cases of unspecified gastroenteritis/diarrhea among U.S. active component service members during 2010–2019. Unspecified gastroenteritis/diarrhea diagnoses accounted for 98.8% of identified incident cases (4,135.1 cases per 100,000 person-years [p-yrs]). Campylobacter was the most frequently identified specific etiology (17.6 cases per 100,000 p-yrs), followed by nontyphoidal Salmonella (12.7 cases per 100,000 p-yrs), norovirus (10.8 cases per 100,000 p-yrs), E. coli (7.5 cases per 100,000 p-yrs) and Shigella (3.2 cases per 100,000 p-yrs). Crude annual rates of norovirus, E. coli, Campylobacter, and Salmonella infections and unspecified gastroenteritis/diarrhea increased between 2010 and 2019 while rates of Shigella infections were relatively stable. Among deployed service members during the 10-year period, only 150 cases of the 5 specific causes of gastroenteritis were identified but a total of 20,377 cases of unspecified gastroenteritis/diarrhea were diagnosed (3,062.9 per 100,000 deployed p-yrs).

Background

Acute gastrointestinal (GI) infections and diarrheal disease have been the perennial cause of significant morbidity in military personnel in both deployed and nondeployed settings.1,2 In American military personnel, acute diarrheal illness was the most commonly reported noncombat disease among deployed personnel during Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom.3 More recent analyses of the burden of diarrheal disease among active component U.S. service members estimated that diarrheal diseases accounted for 42,601 health care encounters affecting 36,387 service members in 2019.4

Acute GI infections can be caused by many bacterial, viral, or parasitic pathogens; however, studies in military populations have often focused on Campylobacter spp., nontyphoidal Salmonella spp., Shigella spp., norovirus, or Escherichia coli as pathogens responsible for a majority of GI infections.5–7 In 2017, the Medical Surveillance Monthly Report (MSMR) published estimated incidence rates of diagnoses of Campylobacter, nontyphoidal Salmonella, Shigella, norovirus, and E. coli infections among active component service members during 2007–2016.8–11 The current report updates and expands upon these previous analyses by estimating incidence rates of diagnoses of GI infections attributed to the aforementioned 5 pathogens as well as diagnoses of unspecified gastroenteritis/diarrhea among active component service members between 2010 and 2019.

Methods

The surveillance period was 1 Jan. 2010 through 31 Dec. 2019. The surveillance population consisted of all active component service members of the U.S. Armed Forces who served in the Army, Navy, Air Force, or Marine Corps at any time during the 10-year surveillance period.

Diagnoses of pathogen-specific acute GI infections (Campylobacter, nontyphoidal Salmonella, Shigella, norovirus, or E. coli) and unspecified gastroenteritis/diarrhea were ascertained from records of reports of notifiable medical events and from administrative records of all medical encounters of individuals who received care in fixed (i.e., not deployed or at sea) medical facilities of the Military Health System (MHS) or civilian facilities in the Click to closePurchased CareThe TRICARE Health Program is often referred to as purchased care. It is the services we “purchase” through the managed care support contracts.purchased care system. All such records are maintained in the Defense Medical Surveillance System. In addition, acute GI infection cases were ascertained from Navy and Marine Corps Public Health Center records of laboratory identification of GI pathogens in stool or rectal samples tested in laboratories of the MHS.

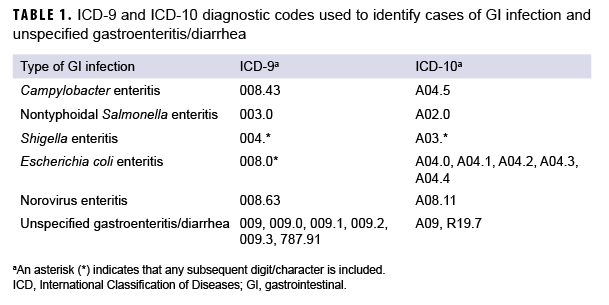

For surveillance purposes, an incident case of acute GI infection was defined as any one of the following: 1) a laboratory confirmed identification of GI infection in a stool or rectal sample, 2) a reportable medical event record of "confirmed" GI infection, 3) a single hospitalization with any of the defining diagnoses for acute GI infections in any diagnostic position, or 4) a single outpatient encounter with any of the defining diagnoses for GI infections in any diagnostic position (Table 1). An incident case of unspecified gastroenteritis/diarrhea was defined as 1 hospitalization or outpatient medical encounter with any of the case defining diagnoses of diarrhea in any diagnostic position. (Table 1).

An individual could be considered a case once every 180 days for each of the 5 types of acute GI infections and unspecified gastroenteritis/diarrhea. The incidence date was considered the date of the earliest rectal or fecal sample that was confirmed positive for each acute GI infection, the date documented in a reportable medical event report for each acute GI infection, or the date of the first hospitalization or outpatient medical encounter that included the defining diagnosis of a case of acute GI infection/diarrhea. Incidence rates were calculated as the number of cases per 100,000 person-years (p-yrs).

Cases of acute GI infections and unspecified gastroenteritis/diarrhea occurring during deployments were analyzed separately. These cases were identified from the medical records of deployed service members whose health care encounters were documented in the Theater Medical Data Store (TMDS). An incident case during deployment was based on a single medical encounter with a diagnosis recorded in the TMDS that occurred between the start and end dates of a service member' deployment record.

Results

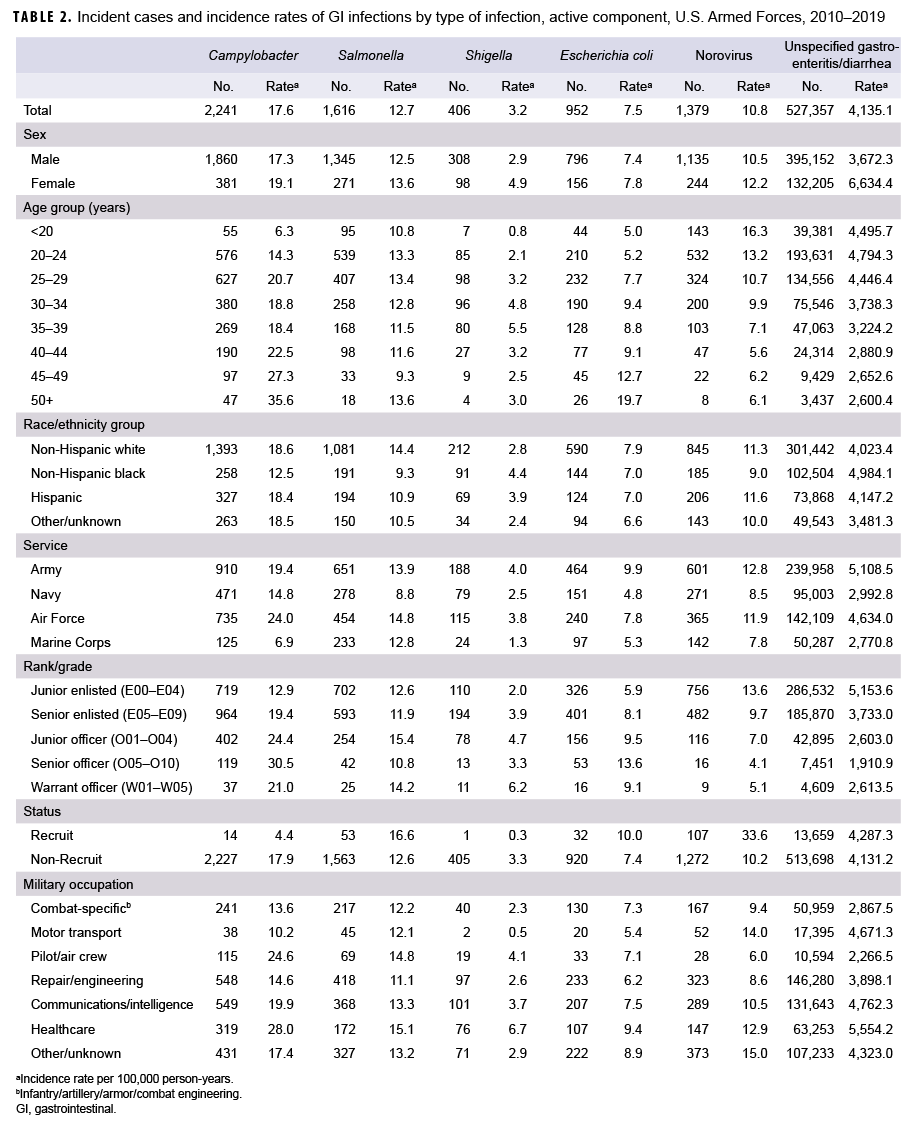

During 2010–2019, there were 2,241 diagnosed cases of Campylobacter infections, 1,616 of Salmonella infections, 406 of Shigella infections, 952 of E. coli infections, 1,379 of norovirus infections, and 527,357 diagnosed cases of unspecified gastroenteritis among active component service members (Table 2). The crude overall incidence rates per 100,000 p-yrs were 17.6 for Campylobacter infections, 12.7 for Salmonella infections, 3.2 for Shigella infections, 7.5 for E. coli infections and 10.8 for norovirus infections. The crude overall incidence rate of unspecified gastroenteritis/ diarrhea (4,135.1 per 100,000 p-yrs) was more than 75 times the combined overall rates of acute GI infections attributable to the 5 specific pathogens of interest.

Examination of overall incidence rates by demographic characteristics showed that, compared with males, females had higher rates of all 5 types of acute GI infections and unspecified gastroenteritis/ diarrhea (Table 2). Active component service members aged 45 years or older had the highest overall rates of Campylobacter and E. coli infections. Compared with those in older age groups, younger service members had the highest rates of norovirus infection and unspecified gastroenteritis/diarrhea. For Shigella infections, service members between 35 and 39 years old had the highest overall incidence rate. Relative to those in other race/ethnicity groups, non-Hispanic black service members had lower rates of Campylobacter, Salmonella, and norovirus infections but the highest rates of Shigella infections and unspecified gastroenteritis/diarrhea (Table 2). Across the services, members of the Army and Air Force had higher rates of all 5 types of acute GI infections and unspecified gastroenteritis/diarrhea compared with members of the other services. Marine Corps members had the lowest overall rates of Campylobacter, Shigella, and norovirus infections as well as the lowest rate of unspecified gastroenteritis/diarrhea. With the exception of Campylobacter and Shigella infections, recruits had higher overall incidence rates compared with nonrecruits. Service members in health care occupations had the highest overall rates of all types of GI infections, except for norovirus, compared with those working in other military occupations.

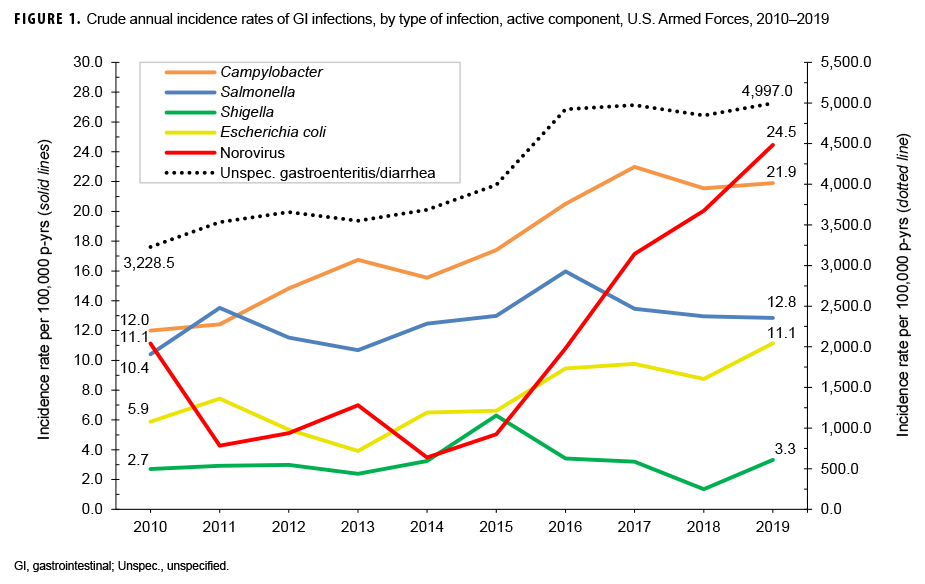

Over the course of the 10-year surveillance period, crude annual incidence rates of E. coli infections and unspecified gastroenteritis/diarrhea increased by 89.6% and 54.8%, respectively. Crude annual rates of Campylobacter infections increased from 2010 through 2017 (82.6%) and then were relatively stable for the remainder of the surveillance period. Crude annual rates of norovirus infections decreased from 11.1 per 100,000 p-yrs in 2010 to a low of 3.5 per 100,000 p-yrs in 2014, after which rates increased steadily to a peak of 24.5 per 100,000 p-yrs in 2019. Annual rates of Salmonella infections fluctuated between a low of 10.4 per 100,000 p-yrs in 2010 and a high of 16.0 per 100,000 p-yrs in 2016. Annual rates of Shigella infections were relatively stable during the 10-year period and, with the exception of 2015, were consistently lower than the rates of the other types of GI infections (Figure 1).

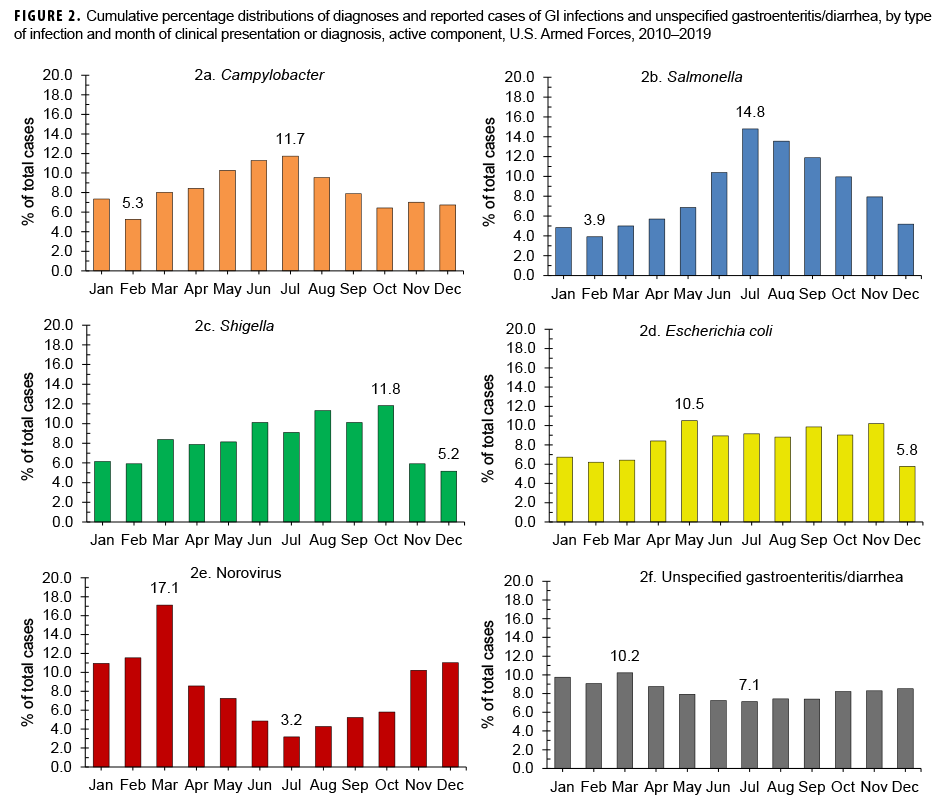

Between 2010 and 2019, the highest percentages of cases of infection by the bacterial pathogens of interest tended to be diagnosed and/or reported during the warmer months in the Northern Hemisphere (Figures 2a–2d). The most pronounced seasonal patterns were seen for cases of Campylobacter and Salmonella infections; the highest percentages of total Campylobacter cases were diagnosed from May through Aug. (Figure 2a) and the majority of total Salmonella infection cases were diagnosed between June and Oct. (60.6%) (Figure 2b). Unlike cases of infection by these bacterial pathogens, the majority of total norovirus infection cases were diagnosed during Nov. –March (60.8%), with the highest percentage of total cases in March (Figure 2e). The highest percentage of unspecified gastroenteritis/diarrhea cases was diagnosed in March (10.2%); however, the distribution of monthly percentages for unspecified gastroenteritis/diarrhea showed the least variation compared to those of the other 5 types of GI infection (Figure 2f).

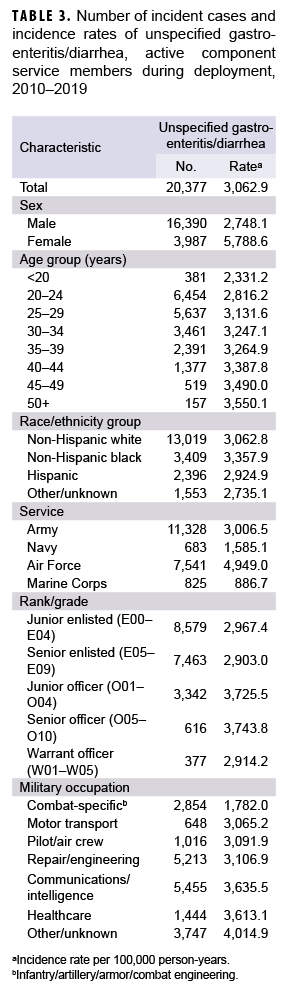

During the 10-year surveillance period, there were 11 diagnosed cases of Campylobacter infections, 56 of Salmonella infections, 11 of Shigella infections, 43 of E. coli infections, and 29 of norovirus infections among deployed active component service members (data not shown). The paucity of cases precluded any attempts to identify demographic patterns of infection during deployment. A total of 20,377 cases of unspecified gastroenteritis/diarrhea were diagnosed during the surveillance period among deployed active component service members for a crude overall incidence rate of 3,062.9 per 100,000 deployed p-yrs. Compared to their respective counterparts, females, those aged 50 years or older, non-Hispanic blacks, Air Force members, and commissioned officers had higher overall rates of unspecified gastroenteritis/diarrhea. Deployed active component service members in other/unknown military occupations, communications/intelligence, and health care had higher overall rates of unspecified gastroenteritis/diarrhea compared to those working in other occupations (Table 3).

Editorial Comment

In the current analysis, the vast majority (98.8%) of cases identified during 2010–2019 represented diagnoses of unspecified gastroenteritis/diarrhea. The crude overall incidence rate of unspecified gastroenteritis/diarrhea was considerably higher than the combined overall rates of GI infections attributable to the 5 pathogens of interest. For acute GI infections with identified bacterial etiologies, the highest incidence rates were for Campylobacter infections, followed by Salmonella, E. coli, and Shigella. Crude annual incidence rates of all pathogen-specific acute GI infections except Shigella increased over the course of the 10-year surveillance period. Rates of norovirus infections rose by the highest percentage overall (119.9%), with the greatest slope of increase occurring between 2014 and 2019. Crude annual rates of unspecified gastroenteritis/diarrhea also increased during this period while rates of Shigella infections were relatively stable.

Comparatively few diagnoses of the pathogen-specific acute GI infections of interest were ascertained from TMDS records of deployed service members' health care encounters during the 10-year study period. While acute diarrheal illness is common in the deployed setting, many cases will not undergo laboratory testing. This can be due to the self-limited nature of the condition, potentially rapid resolution of cases as a result of effective treatment, or limited laboratory capabilities in theater.12

It is important to note that the incidence rates reported here likely underestimate the true burden of acute GI infections and diarrheal disease in this population. To be counted as a case in this analysis, military personnel had to seek medical care and receive a diagnosis of acute GI infection or diarrhea, have a positive laboratory result for 1 of the specified GI pathogens, or be reported as a case in the reportable medical event system. However, many individuals with GI illnesses do not seek medical care for their illnesses. In a recent systematic review of traveler' diarrhea (TD), incidence rates of TD were higher in studies that relied on self-report rather than on clinical diagnosis or reportable medical events.5 he same review reported that only 38% of individuals reporting diarrheal illnesses sought medical care.5 Another limitation of the current analysis is that many acute GI infections were not attributed to particular pathogens because of the lack of testing to determine specific etiologies. Finally, the laboratory data used in this analysis did not include laboratory tests conducted in the civilian purchased care system, so positive tests in that system are not reflected in this report.

Despite the likely underascertainment of total cases of pathogen-specific acute GI infection, the counts and rates of the types of infections reported here represent findings consistent with earlier MSMR analyses8–11 and the known epidemiology of these pathogens.13 Since no pattern of seasonality was observed for unspecified gastroenteritis/diarrhea, it is unclear whether these cases were predominantly caused by viral or bacterial pathogens. Given that unspecified gastroenteritis and diarrheal illnesses remain prevalent among military personnel and can significantly degrade service members' readiness for duty, increased diagnostic testing of nonspecific acute GI infections is warranted to further elucidate which GI pathogens are the most prevalent in this population.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank the Navy and Marine Corps Public Health Center, Portsmouth, VA, for providing laboratory data for this analysis.

References

- Connor P, Farthing MJ. Travellers' diarrhoea: a military problem? J R Army Med Corps. 1999;145(2):95–101.

- Riddle MS, Savarino SJ, Sanders JW. Gastrointestinal Infections in Deployed Forces in the Middle East Theater: An Historical 60 Year Perspective. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;93(5):912–917.

- Riddle MS, Tribble DR, Putnam SD, et al. Past trends and current status of self-reported incidence and impact of disease and nonbattle injury in military operations in Southwest Asia and the Middle East. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(12):2199–2206.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Absolute and relative morbidity burdens attributable to various illnesses and injuries, non-service member beneficiaries of the Military Health System, 2019. MSMR. 2020;27(5):39–49.

- Olson S, Hall A, Riddle MS, Porter CK. Travelers' diarrhea: update on the incidence, etiology and risk in military and similar populations—1990–2005 versus 2005–2015, does a decade make a difference?. Trop Dis Travel Med Vaccines. 2019;5:1.

- Brooks KM, Zeighami R, Hansen CJ, McCaffrey RL, Graf PCF, Myers CA. Surveillance for norovirus and enteric bacterial pathogens as etiologies of acute gastroenteritis at U.S. military recruit training centers, 2011-2016. MSMR. 2018;25(8):8–12.

- Mullaney SB, Hyatt DR, Salman MD, Rao S, McCluskey BJ. Estimate of the annual burden of foodborne illness in nondeployed active duty US Army Service Members: five major pathogens, 2010-2015. Epidemiol Infect. 2019;147:e161.

- O'Donnell FL, Stahlman S, Oh GT. Incidence of Campylobacter intestinal infections, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2007–2016. MSMR. 2017;24(6):2–5.

- Williams VF, Stahlman S, Oh GT. Incidence of nontyphoidal Salmonella intestinal infections, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2007– 2016. MSMR. 2017;24(6):6–10.

- Williams VF, Stahlman S, Oh GT. Incidence of Shigella intestinal infections, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2007–2016. MSMR. 2017;24(6):11–15.

- Clark LL, Stahlman S, Oh GT. Using records of diagnoses from health care encounters and laboratory test results to estimate the incidence of norovirus infections, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2007–2016: limitations to this approach. MSMR. 2017;24(6):16–19.

- Riddle MS, Martin GJ, Murray CK, et al. Management of acute diarrheal illness during deployment: A deployment health guideline and expert panel report. Mil Med. 2017;182(S2):34–52.

- Graves NS. Acute gastroenteritis. Prim Care Clin Office Pract. 2013;40(3):727–741.