What Are the New Findings?

Surveillance data of probable and confirmed COVID-19 among MHS beneficiaries have been collected and evaluated on a daily basis since the COVID-19 pandemic began. This study describes the characteristics of COVID-19 cases among MHS beneficiaries to date, including the prevalence of comorbidities and percent hospitalized.

What Is the Impact on Readiness and Force Health Protection?

Detailed data on demographic characteristics and underlying medical conditions can inform targeted communication to encourage persons in at-risk groups to practice preventive measures and promptly seek medical care if they become ill. Enhanced surveillance efforts can enable actions to prevent and control the current COVID-19 epidemic, which threatens the health of the force.

Abstract

The U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services declared a public health emergency in the U.S. on 31 Jan. 2020 in response to the spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). On 20 March 2020, the President of the U.S. proclaimed that the COVID-19 outbreak in the U.S. constituted a national emergency, retroactive to 1 March 2020. Between 1 Jan. and 30 Sept. 2020, a total of 53,048 Military Health System (MHS) beneficiaries were identified as confirmed or probable cases of COVID-19 infection. The majority of cases were male (69.1%) and 45.4% were aged 20–29 years. The demographic and clinical characteristics of these cases varied by beneficiary type (active component service members, recruits, Reserve/Guard, dependents, retirees, and cadets). Of the total cases, 35.8% had been diagnosed with at least 1 of the comorbidities of interest, and 20.0% had been diagnosed with 2 or more comorbidities. The most common comorbidities present in COVID-19 cases were any cardiovascular diseases (12.7%), obesity or overweight (11.1%), metabolic diseases (10.5%), hypertension (9.9%), neoplasms (7.9%), any lung diseases (7.5%), substance use disorders, including nicotine dependence (5.4%), and asthma (3.2%). There were a total of 1,803 hospitalizations (3.4%) and 84 deaths (0.2%).

Background

A novel (new) coronavirus was identified as the cause of a cluster of pneumonia cases in Wuhan, a city in the Hubei province of China, in Dec. 2019. This virus, now named SARSCoV-2 due to its similarity to the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV), is the cause of the current pandemic with considerable global morbidity and mortality.1–5 Genomic analysis revealed that SARS-CoV-2 is phylogenetically related to severe acute respiratory syndrome-like (SARS-like) bat viruses, suggesting that bats could be the possible primary reservoir.6 The intermediate source of origin and transfer to humans is still not known. Since Dec. 2019, continuous person-to-person spread within communities has occurred worldwide. This virus is thought to spread primarily from person to person, and mainly through respiratory droplets produced when an infected person coughs or sneezes.7 These droplets can land in the mouths or noses of people who are nearby or conceivably be inhaled into the lungs.7 Spread is more likely when people are in close contact with one another (within about 6 feet).7 The virus can cause illness varying from mild to severe, including illness resulting in death.8 Approximately 18–31% of infected persons remain asymptomatic throughout the course of their infection,9 but may still transmit SARS-CoV-2 infection to other susceptible persons.9,10

As of 1 Nov. 2020, the COVID-19 Dashboard prepared by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering at Johns Hopkins University had reported over 46.4 million COVID-19 cases and 1.2 million deaths worldwide and over 9.1 million cases and over 230 thousand deaths in the U.S.4 Notably, most symptomatic COVID-19 cases are mild,11 but severe disease can be found in any demographic group.12 Older individuals and those with underlying medical conditions are at higher risk of serious illness and death,13 and risk in the U.S. and worldwide increases with advancing age.12 Previous reports suggested that a majority of COVID-19 deaths have occurred among adults aged 60 years or older and among persons with serious underlying health conditions.8,13,14 This observation underscores the need to carefully track the prevalence of selected underlying health conditions among MHS beneficiaries, including retirees.

Early Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) preliminary analysis13 of U.S. data indicated that persons with underlying health conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and obesity appeared to be at higher risk for severe COVID-19-associated disease than persons without these conditions. Severe illness from COVID-19 is characterized by a clinical course that results in hospitalization, admission to the intensive care unit (ICU), intubation or mechanical ventilation, or death. CDC recently updated its website to include additional underlying medical conditions that might increase one's risk for severe illness from the virus that causes COVID-19. These underlying medical conditions include cancer, chronic kidney disease, COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), heart conditions such as heart failure, coronary artery disease, or cardiomyopathies, immunocompromised state (weakened immune system) from solid organ transplant, obesity (body mass index [BMI] of 30 kg/m2 or higher but < 40 kg/m2), severe obesity (BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2), pregnancy, sickle cell disease, smoking, and type 2 diabetes mellitus.14

Many published reports have summarized data on the risk of severe disease and death in COVID-19 patients with specific comorbidities.13–17 Fewer reports in the MHS beneficiary population have been published.15,17–19 In general, Department of Defense (DOD) laboratory testing guidance is to test patients for COVID-19 who are symptomatic, in areas with local, community transmission, or have an increased exposure risk or risk for potential severe outcomes.20 However, asymptomatic service members may also be screened to decrease operational risk (e.g., training commands, shipboard settings).21 There are published reports of outbreaks among military populations that summarize the challenges of adhering to COVID-19 mitigation strategies.17–19 These analyses of military populations concluded that young, healthy persons can contribute to community asymptomatic spread of infection in close-quarters living conditions and that a higher burden of disease was also associated with comorbid conditions. The objectives of this study were to characterize the population of MHS beneficiaries infected with COVID-19 through 30 Sept. 2020 and to report the prevalence of selected underlying conditions.

Methods

Since March 2020, the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Division (AFHSD) has maintained a case list of MHS beneficiaries with COVID-19. This list is updated daily and currently comprises Composite Health Care System (CHCS) Health Level 7 (HL7)-formatted and MHS Genesis laboratory positive test results extracted by the Navy and Marine Corps Public Health Center Epi Data Center (for all services), as well as medical event reports of laboratory confirmed and probable COVID-19 infection reported to the Disease Reporting System Internet (DRSi), and validated by the U.S. Army Public Health Center and the U.S. Air Force School of Aerospace Medicine. The DRSi is the DOD's web-based surveillance system where confirmed and probable cases, as defined in the Armed Forces Reportable Medical Events Guidelines,22 are reported by installation public health personnel. At the time of this report, the DRSi COVID-19 case definition was pending publication; however, DOD uses the CDC's case definition for surveillance.23 AFHSD also maintains the Defense Medical Surveillance System (DMSS), a continuously expanding relational database of personnel and medical data. For this analysis, the DMSS was used to identify hospitalizations for COVID-19 and to extract demographic information that was missing from the case list. The DMSS was also used to identify comorbidities from administrative records of inpatient and outpatient medical encounters, which included encounters from fixed military treatment facilities as well as outsourced care reimbursed by TRICARE.

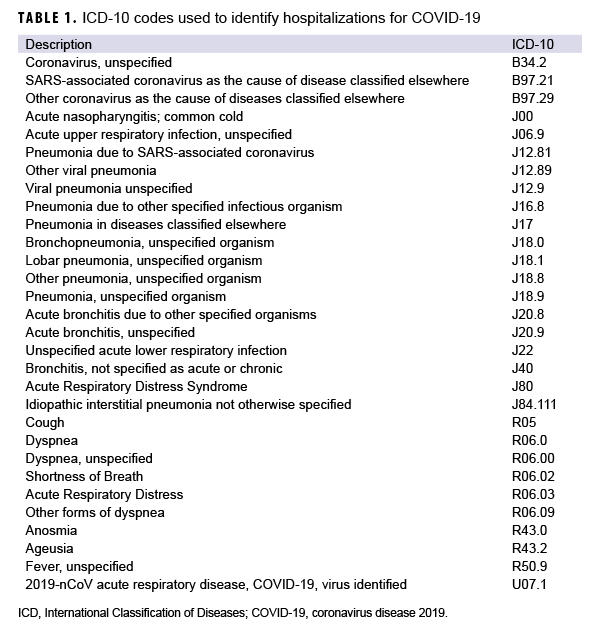

The surveillance population included all Military Health System (MHS) beneficiaries, excluding DOD civilian employees and contractors. Hospitalization status was determined using information recorded in DRSi about whether the case was ever hospitalized and using inpatient encounter data extracted from DMSS. For the latter, a hospitalization for COVID-19 was defined by having an inpatient record in DMSS occurring within 30 days after the first positive laboratory record for COVID-19, with the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision [ICD-10] code U07.1 in the first or second diagnostic position, or a diagnosis for COVID-like illness in the first or second diagnostic position (Table 1).

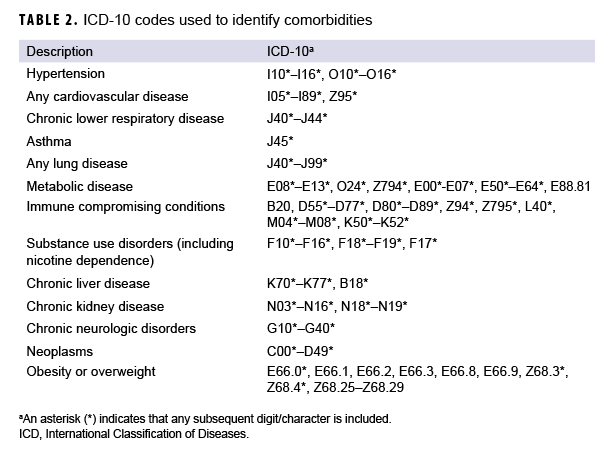

An individual was considered to have a comorbidity if there was an inpatient or outpatient encounter containing an ICD-10 code for that comorbidity in any diagnostic position between 1 Jan. 2019 and 30 Sept. 2020. This time period was chosen to more conservatively estimate the prevalence of comorbidities at the time of COVID-19 infection, by identifying individuals who had recently sought care for that condition. The list of ICD-10 codes for the comorbidities of interest can be found in Table 2. These comorbidities were identified based on those reported in the CDC's weekly surveillance summary of COVID-19 activity and underlying medical conditions14,24 and on a review of existing literature.15,25,26 Deaths were identified from the DRSi data and from reports through the Armed Forces Medical Examiner System (AFMES).

Results

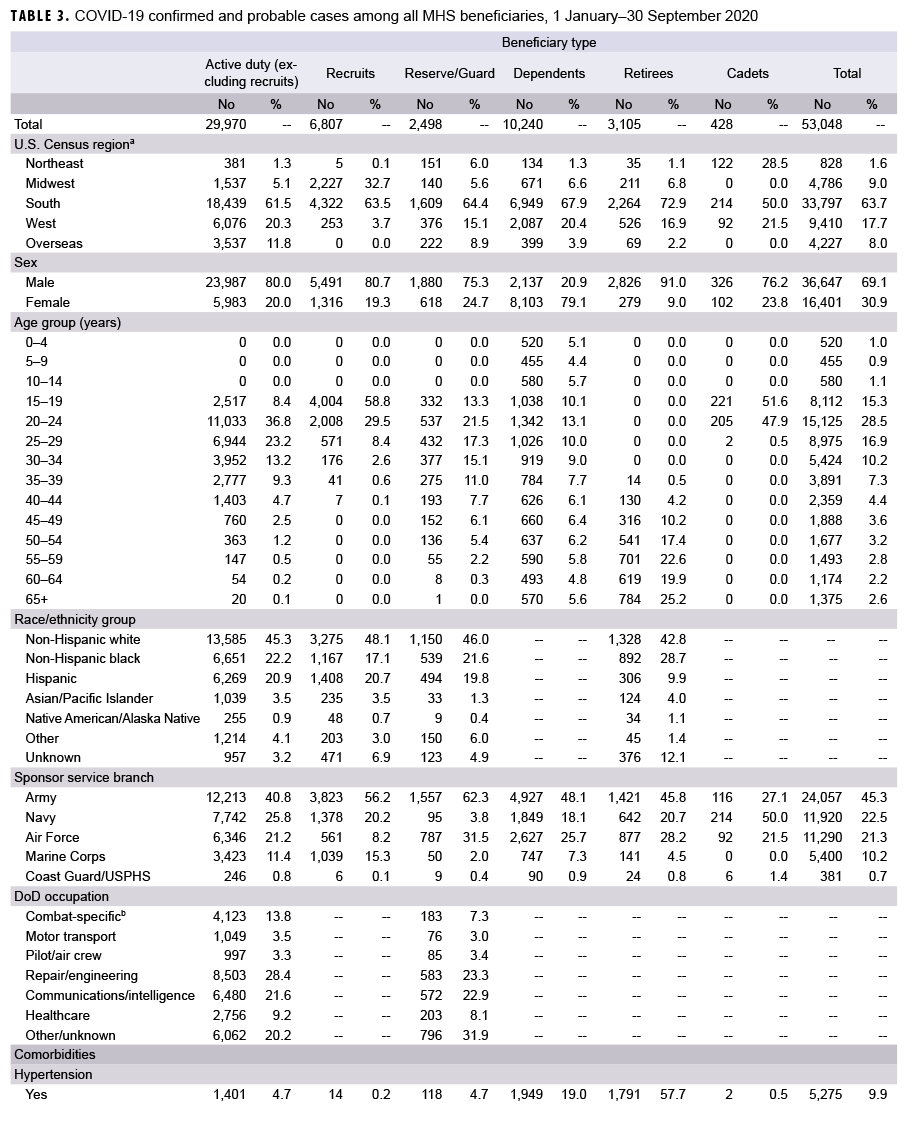

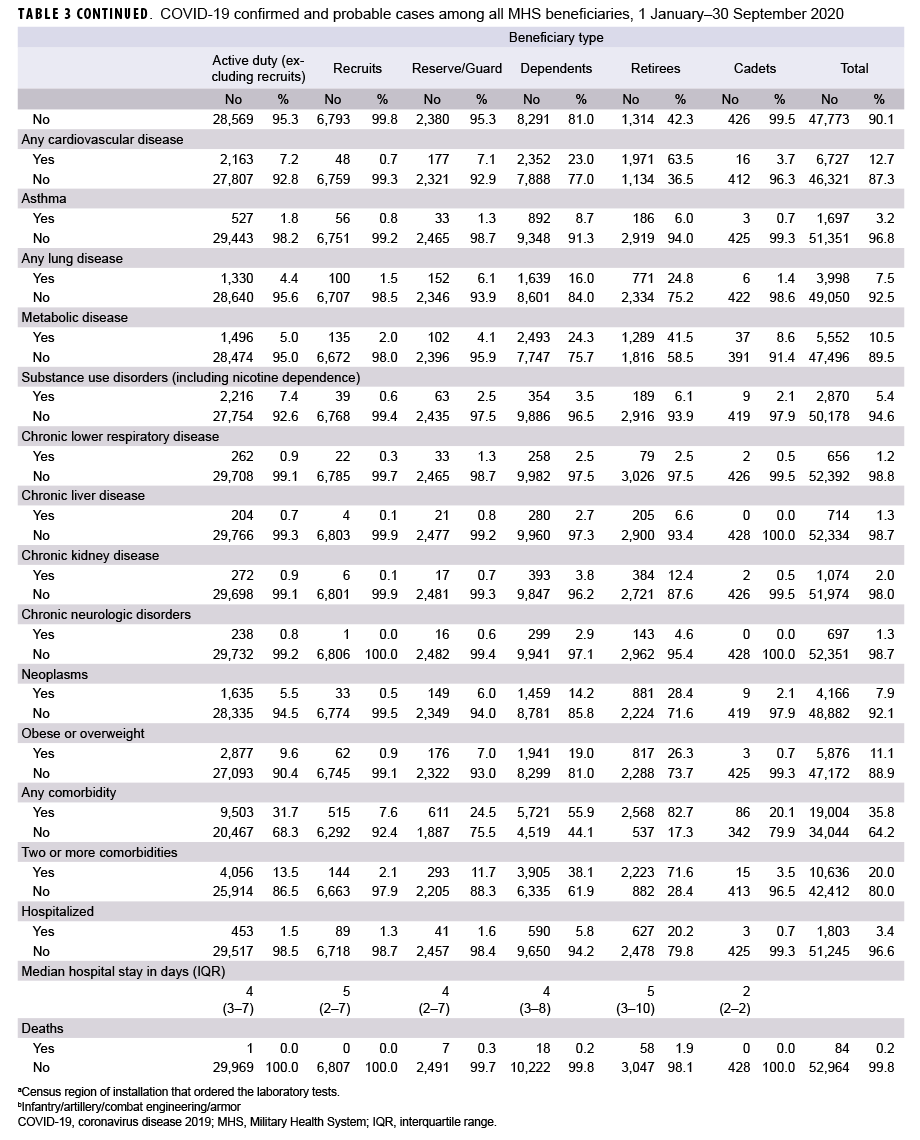

As of 30 Sept. 2020, a total of 53,048 MHS beneficiaries were identified as confirmed or probable cases of COVID-19 (Table 3). Of these, 35.8% had been diagnosed with at least 1 of the comorbidities of interest, and 20.0% had been diagnosed with 2 or more comorbidities. There were a total of 1,803 hospitalizations (3.4%) and 84 deaths (0.2%). The demographic and clinical characteristics of these cases varied by beneficiary type.

Active duty

A total of 29,970 active duty servicemembers were detected with the SARSCoV-2 virus infections as of 30 Sept. 2020 (Table 3). The largest demographic proportions of cases were among those who were male (80.0%), aged 20–24 years (36.8%), non-Hispanic White (45.3%), and in the Army (40.8%). Almost one-third (31.7%) of cases were diagnosed with a comorbidity, and 13.5% were diagnosed with 2 or more comorbidities. Of the comorbidities that were assessed, the most commonly diagnosed comorbidities were obesity or overweight (n=2,877; 9.6%), substance use including nicotine dependence (n=2,216; 7.4%), cardiovascular disease (n=2,163; 7.2%), neoplasms (n=1,635; 5.5%), and metabolic disease (n=1,496; 5.0%). A total of 453 active duty service members (1.5%) were hospitalized, with a median hospital stay of 4 days (interquartile range [IQR]=3–7). During the surveillance period, there was 1 death among the active duty COVID-19 cases.

Recruits

A total of 6,807 COVID-19 cases were identified among recruits (Table 3). The largest proportions of cases were male (80.7%), aged 15–19 years (58.8%), non-Hispanic White (48.1%), and in the Army (56.2%). Less than one-tenth (7.6%) of cases were diagnosed with a comorbidity, and only 2.1% were diagnosed with 2 or more comorbidities. Of the comorbidities that were assessed, the most commonly diagnosed conditions were metabolic disease (n=135; 2.0%), lung disease (n=100; 1.5%), and obesity or overweight (n=62; 0.9%). A total of 89 recruits (1.3%) were hospitalized, with a median hospital stay of 5 days (IQR=2–7). There were no deaths among recruit cases during the surveillance period.

Cadets

A total of 428 cadets were infected with COVID-19 by the end of the surveillance period (Table 3). The largest proportions of cases were male (76.2%) and in the Navy (50.0%). Almost all of the cases were in the 15–19 and 20–24 year age categories (99.5%). Data on race/ethnicity group were not available for cadets. About one-fifth (20.1%) were diagnosed with a comorbidity, and 3.5% were diagnosed with 2 or more comorbidities. The most commonly diagnosed comorbidities were metabolic disease (n=37; 8.6%), cardiovascular disease (n=16; 3.7%), neoplasms (n=9; 2.1%), and substance use including nicotine dependence (n=9; 2.1%). Only 3 (0.7%) cadets were hospitalized, and all 3 cases spent 2 days in the hospital. During the surveillance period, there were no deaths among cadet cases.

Reserve/Guard

A total of 2,498 COVID-19 cases were identified among reserve and guard service members (Table 3). The largest proportions of cases were male (75.3%), aged 20–24 years (21.5%), non-Hispanic white (46.0%), and in the Army (62.3%). About one-quarter (24.5%) of cases were diagnosed with a comorbidity, and 11.7% were diagnosed with 2 or more comorbidities. Of the comorbidities that were assessed, the most commonly diagnosed conditions were cardiovascular disease (n=177; 7.1%), obesity or overweight (n=176; 7.0%), lung disease (n=152; 6.1%), and neoplasms (n=149; 6.0%). A total of 41 reserve/guard members (1.6%) were hospitalized, with a median hospital stay of 4 days (IQR=2–7). There were 7 deaths among reserve and guard cases.

Dependents

A total of 10,240 dependents were identified as COVID-19 cases (Table 3). The largest proportions of cases were female (79.1%) and dependents of an Army service member (48.1%). There was a wide range in the distribution of age among the dependent cases, but the age categories with the largest numbers of cases were 20–24 years (13.1%), 15–19 years (10.1%), and 25–29 years (10.0%). Data on race/ethnicity group were not available for dependents. More than half (55.9%) were diagnosed with a comorbidity, and 38.1% were diagnosed with 2 or more comorbidities. The most commonly diagnosed comorbidities were metabolic disease (n=2,493; 24.3%), cardiovascular disease (n=2,352; 23.0%), hypertension (n=1,949; 19.0%), and obesity or overweight (n=1,941; 19.0%). A total of 590 (5.8%) dependent cases were hospitalized, with a median hospital stay of 4 days (IQR=3–8). There were 18 (0.2%) deaths among dependent cases.

Retirees

A total of 3,105 retirees were identified as COVID-19 cases. The largest proportions of cases were male (91.0%), non-Hispanic White (42.8%), and formerly in the Army (45.8%). The age categories with the largest numbers of cases were 65 years or older (25.2%), 55–59 years (22.6%), and 60–64 years (19.9%). A large majority of cases (82.7%) were diagnosed with a comorbidity, and 71.6% were diagnosed with 2 or more comorbidities. The most commonly diagnosed comorbidities included cardiovascular disease (n=1,971; 63.5%), hypertension (n=1,791; 57.7%), metabolic disease (n=1,289; 41.5%), and neoplasms n=881; 28.4%). A total of 627 (20.2%) retiree cases were hospitalized, with a median hospital stay of 5 days (IQR=3–10). There were 58 (1.9%) deaths among retiree cases during the surveillance period.

Editorial Comment

This report describes the demographic characteristics and prevalence of comorbidities among incident COVID-19 cases across MHS beneficiary categories. Not surprisingly, cases among service members (including recruits and cadets) were most commonly diagnosed in young, non-Hispanic white males, which follows the expected demographic distributions of these groups. Among active duty service members, the largest proportion of cases was among Army members (40.8%), which is generally expected since the Army makes up over one third of the active component population. Cases among dependents tended to occur among females, of whom many were spouses of service members, and cases among retirees tended to occur among older males. Of note, over 56% of the MHS population that was diagnosed with COVID-19 were active duty members and 56.5% were between the ages of 20 and 34 years.

Overall, 35.8% of COVID-19 cases among MHS beneficiaries were diagnosed with at least 1 of the comorbidities of interest, and 20.0% had been diagnosed with 2 or more comorbidities. This is an important observation because underlying medical conditions such as cancer, chronic kidney disease, heart conditions, diabetes, and obesity can put adults of all ages at increased risk of severe illness from SARS-COV-2.14 However, the most prevalent comorbidities varied by beneficiary category. Among service member COVID-19 cases (including active duty, reserve/guard, recruits, and cadets), obesity/overweight, cardiovascular disease, and metabolic disease were among the top comorbidities. The current findings differ somewhat from a previous analysis of active component Army members which identified "other chronic disease" and "neurologic disorder" as the leading comorbidities among cases. However, this difference in findings is likely due, at least in part, to differences in the methodologies employed to ascertain cases (e.g., chart review versus use of ICD-10 codes in administrative data) and the case definitions used for the comorbidities.

In 2019, the overall prevalence of obesity among active component service members was 17.9% compared to 16.3% in 2015.27 This same report also pointed out that the prevalence of obesity was greater among males (18.8%) than females (14.3%) and in older compared to younger service members.27 Obesity is relevant to military health because it adversely impacts physical performance and military readiness and is associated with long-term health problems such as hypertension, diabetes, coronary heart disease, stroke, cancer, and risk for all-cause mortality. The findings presented here further suggest that obesity presents another concern for force health protection in relation to COVID-19, as obesity is one of the most commonly diagnosed comorbidities among active duty member cases.

In the U.S., cardiovascular diseases such as heart attacks, strokes, and heart failure are the leading causes of death and over 30 million adults are currently diagnosed with heart disease (12.1%).28 In the current analysis, cardiovascular disease was a leading comorbidity among retiree COVID-19 cases. This is not surprising given that the prevalence of cardiovascular disease (to include coronary heart disease, heart failure, stroke, and hypertension) increases with advancing age in both males and females.29

There are some limitations to this study. One primary limitation is the lack of complete denominator data for all beneficiary groups, which hindered the ability to make comparisons of rates of infection across beneficiary groups. In addition, it is difficult to compare the prevalence of comorbidities and percentage of hospitalizations with data in U.S. civilians because of the differences in demographic compositions of these groups and in the methods of data collection. Also, military service members are likely to be healthier than the general U.S. population because of selection on good health before and during military service, better access to medical care during military service, and a requirement to maintain a certain standard of physical well-being during service. It is also important to note that the asymptomatic nature of many cases of SARSCoV-2 infections precludes the identification and diagnosis of all such infections among MHS beneficiaries and leads to underestimates of the true incidence and prevalence of this condition. Finally, the prevalence of comorbidities is likely underestimated in this report because cases of comorbidity were only counted if there was a diagnosis dating back to 1 Jan. 2019. In particular, the co-occurrence of obesity was likely underestimated since it relied on the use of ICD-10 codes instead of BMI.

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to have persistent person-to-person spread in the community worldwide, particularly in certain population groups. Findings presented here draw attention to the necessity to build on present-day disease surveillance efforts to collect and analyze case prevalence data, principally including those with serious underlying health conditions. Continued surveillance of COVID-19 among MHS beneficiaries will be an important part of force health protection efforts to improve the readiness, health, and the well-being of MHS beneficiary populations.

Author affiliations: Epidemiology and Disease Surveillance Department, Allied Health Sciences Directorate, U.S. Army Public Health Command Central Region, Joint Base San Antonio-Fort Sam Houston, TX (Dr. Stidham); Armed Forces Health Surveillance Division (Dr. Stahlman); Ergonomics Program, Allied Health Sciences Directorate, U.S. Army Public Health Command Central Region, Joint Base San Antonio-Fort Sam Houston, TX (Dr. Salzar).

Disclaimer: The view(s) expressed herein are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Army Public Health Command Central Region, Armed Forces Health Surveillance Division, U.S. Army Medical Department, U.S. Army Office of the Surgeon General, Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or U.S. Government.

References

- Clark A, Jit M, Warren-Gash C, et al. Global, regional, and national estimates of the population at increased risk of severe COVID-19 due to underlying health conditions in 2020: a modelling study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020; 8 e1003–17.8.

- Kang SJ, Jung SI. Age-Related morbidity and mortality among patients with COVID-19. Infect Chemother. 2020;52(2):154–164.

- Usafacts.org. US Coronavirus Cases and Deaths. https://usafacts.org/visualizations/coronavirus-covid-19-spread-map/. Accessed 26 Oct. 2020.

- COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins. 2020. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html. Accessed 26 Oct. 2020.

- WHO. Novel coronavirus (COVID-19) situation. 2020; published online March 23. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports. Accessed 26 Oct. 2020.

- Shereen MA, Khan S, Kazmi A, Bashir N, Siddique R. COVID-19 infection: origin, transmission, and characteristics of human coronaviruses. J Adv Res. 2020;24:91–98

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 (Coronavirus Disease). Frequently Asked Questions. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/faq.html. Accessed 11 Dec. 2020.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): if you are at higher risk. Get ready for COVID-19 now. Atlanta, GA:US Department of Health and Human Services; 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/specific-groups/high-risk-complications.html. Accessed 11 Dec. 2020.

- Kimball A, Hatfield KM, Arons M, et al. Asymptomatic and presymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections in residents of a long-term care skilled nursing facility - King County, Washington, March 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(13):377–381.

- Treibel TA, Manisty C, Burton M, et al. COVID-19: PCR screening of asymptomatic health-care workers at London hospital. Lancet. 2020;395(10237):1608–1610.

- The Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Emergency Response Epidemiology Team. Vital surveillances:The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19)—China, 2020. China CDC Wkly. 2020;2(8):113–122.

- Bialek S, Boundy E, Bowen V, et al. CDC COVID-19 Response Team. Severe outcomes among patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)—U.S., Feb. 12–March 16, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(12):343–346.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preliminary estimates of the prevalence of selected underlying health conditions among patients with coronavirus disease 2019—U.S., Feb. 12–March 28, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(13):382–386.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. People who are at increased risk for severe illness with certain medical conditions. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-with-medical-conditions.html. Accessed 11 Dec. 2020.

- Kebisek J, Forrest L, Maule A, Steelman R, Ambrose J. Special report: prevalence of selected underlying health conditions among active component Army service members with coronavirus disease 2019, 11 February–6 April 2020. MSMR.2020; 27:50–54.

- Jordan RE, Adab P, Cheng KK. Covid-19:risk factors for severe disease and death. BMJ. 2020;368:m1198.

- Letizia AG, Ramos I, Obla A, et al. SARS-CoV-2 transmission among Marine recruits during quarantine. N Engl J Med. 2020;NEJMoa2029717.

- Kasper MR, Geibe JR, Sears CL, et al. An outbreak of COVID-19 on an aircraft carrier. N Engl J Med. 2020;NEJMoa2019375.

- Michael NL. (2020) SARS-CoV-2 in the U.S. military—Lessons for civil society. N Engl J Med.2020;NEJMe2032179.

- Department of Defense. Force Health Protection (Supplement 6). Guidance for Coronovirus Disease 2019. Laboratory Diagnostic Testing Services. https://www.whs.mil/Portals/75/Coronavirus/Force%20Health%20Protection%20(Supplement%206)%20-%20Department%20of%20Defense%20Guidance%20for%20Coronavirus%20Disease%202019%20Laboratory%20Diagnostic%20Testing%20Services.pdf?ver=2020-04-08-140936-557. Accessed 17 Dec. 2020.

- Department of Defense. Force Health Protection (Supplement 11). Guidance for Coronovirus Disease 2019. Surveillance and Screening with Testing. https://media.defense.gov/2020/Jun/12/2002315485/-1/-1/1/DOD-Guidance-for-COVID-19-Surveillance-and-Screening-with-Testing.pdf. Accessed 17 Dec. 2020.

- Armed Forces Reportable Medical Events. Guidelines and Case Definitions. https://health.mil/Reference-Center/Publications/2020/01/01/Armed-Forces-Reportable-Medical-Events-Guidelines. Accessed 24 Oct. 2020.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS). Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) 2020 Interim Case Definition. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nndss/conditions/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19/case-definition/2020/ Accessed 16 De. 2020.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). COVIDView: A weekly summary of U.S. COVID-19 activity. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/covidview/index.html. Accessed 24 Oct. 2020.

- Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. JAMA. 2020;323(20):2052–2059.

- Guan WJ, Liang WH, Zhao et al. Comorbidity and its impact on 1590 patients with COVID-19 in China: a nationwide analysis. Eur Respir J.2020;55(5):2000547.

- Department of Defense 2019 Health of the Force. https://www.health.mil/Military-Health-Topics/Combat-Support/Armed-Forces-Health-Surveillance-Branch/Reports-and-Publications. Accessed 30 Nov. 2020.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Summary Health Statistics Tables for U.S. Adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2018, Table A-1b, A-1c. https://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/NHIS/SHS/2018_SHS_Table_A-1.pdf. Accessed 23 Nov. 2020.

- American Heart Association. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2019 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/epub/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000659. Accessed 23 Nov. 2020.

-