Abstract

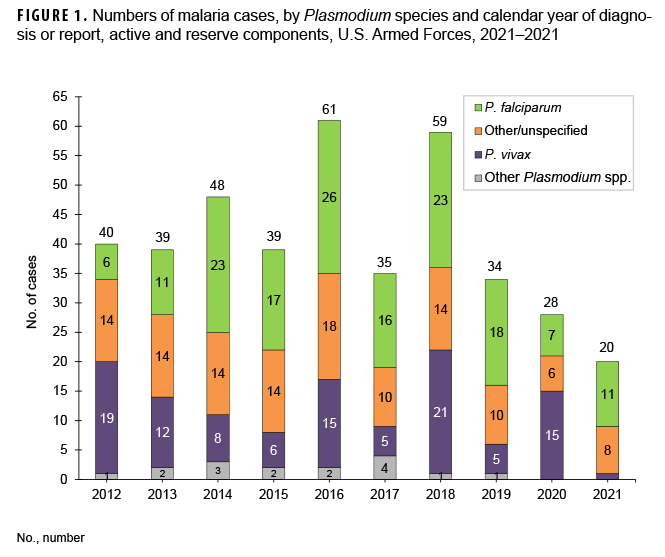

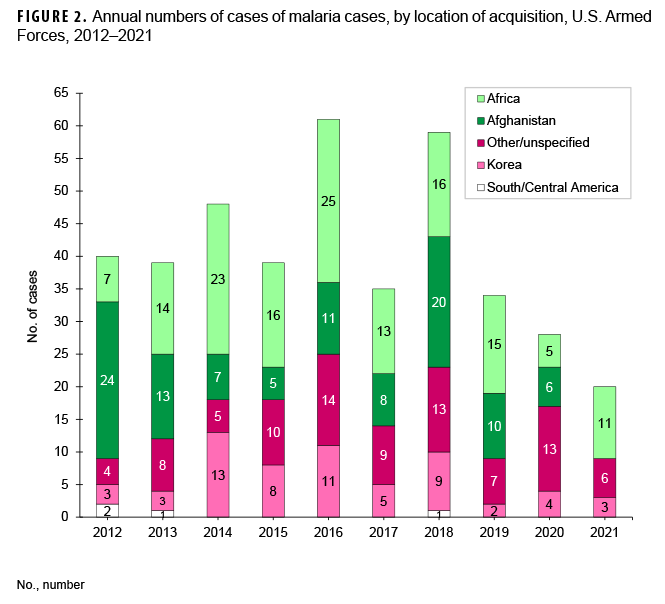

Malaria infection remains an important health threat to U.S. service members who are located in endemic areas because of long-term duty assignments, participation in shorter-term contingency operations, or personal travel. In 2021, a total of 20 service members were diagnosed with or reported to have malaria. This was the lowest number of annual cases during the 10-year surveillance period (i.e., Jan. 2012–Dec. 2021) and represents a 28.6% decrease from the 28 cases identified in 2020. The relatively low numbers of cases during 2012–2021 mainly reflect decreases in cases acquired in Afghanistan, a reduction largely due to the progressive withdrawal of U.S. forces from that country. The percentage of 2021 cases of malaria caused by Plasmodium falciparum (55.0%; n=11) was the highest of any year of the surveillance period; however, the number of cases was the third lowest observed during the surveillance period. The number of malaria cases caused by Plasmodium vivax in 2021 (n=1) was the lowest observed during the surveillance period. The remaining 8 malaria cases were labeled as associated with other/unspecified types of malaria (40.0%). Malaria was diagnosed at or reported from 15 different medical facilities in the U.S.; only 2 were reported outside of the U.S., 1 each in Germany and Africa. Providers of medical care to military members should be knowledgeable of and vigilant for clinical manifestations of malaria outside of endemic areas.

What are the New Findings?

The 2021 total of 20 malaria cases among active and reserve component service members was the lowest annual count of cases during the past 10 years. No malaria cases were acquired from Afghanistan. The 2021 proportion of cases (55.0%) due to P. falciparum was the highest of the 10-year period; however, the case count remained low compared to previous years.

What is the Impact on Readiness and Force Health Protection?

The decrease in total counts of malaria cases during the last decade reflects the reduced numbers of service members exposed to malaria in Afghanistan. The persistent threat from P. falciparum associated with duty in Africa underscores the importance of preventive measures effective against this most dangerous strain of malaria.

Background

Worldwide, the incidence rate of malaria is estimated to have decreased from 71.1 per 1,000 population at risk in 2010 to 57.5 in 2015 and 56.3 in 2019.1 The World Health Organization (WHO) reported a slight increase in the estimated rate in 2020 (59.0 per 1,000 population at risk) which was partially attributed to disruptions in the delivery of malaria services (i.e., prevention, diagnosis, and treatment) due to the COVID-19 pandemic. During 2000–2019, malaria-related deaths decreased steadily from 896,000 in 2000 to 562,000 in 2015 and 558,000 in 2019. In 2020, estimated malaria deaths (627,000) increased 12% compared to 2019, with approximately 68% of the excess deaths attributed to pandemic-related disruptions in malaria services. The remaining 32% of excess deaths is reported to reflect a recent change in WHO's methodology for calculating malaria mortality.1

Countries in Africa accounted for about 95% of worldwide malaria cases and 96% of malaria-related deaths in 2020.1 Six African countries including Nigeria (27%), the Democratic Republic of the Congo (12%), Uganda (5%), Mozambique (4%), Angola (3%), and Burkina Faso (3%) accounted for slightly more than half (55%) of all cases globally.1 Most of these cases and deaths were due to mosquito-transmitted Plasmodium falciparum and occurred among children under 5 years of age,1 but Plasmodium vivax, Plasmodium ovale and Plasmodium malariae can also cause severe disease.1–3 Globally in 2020, 2% of estimated malaria cases were caused by P. vivax.1 It is important to note that, while heightened malaria-control efforts have reduced the incidence of P. falciparum malaria in many areas, the proportion of malaria cases caused by P. vivax has increased in some regions where both parasites coexist (e.g., Djibouti, Pakistan, Venezuela).3,4

Since 2007, the MSMR has published regular updates on the incidence of malaria among U.S. service members (Army reports began in 1999).5–7 The MSMR's focus on malaria reflects both historical lessons learned about this mosquito-borne disease and the continuing threat that it poses to military operations and service members' health. Malaria infected many thousands of U.S. service members during World War II (approximately 695,000 cases), the Korean War (approximately 390,000 cases), and the conflict in Vietnam (approximately 50,000 cases).8,9 More recent military engagements in Africa, Asia, Southwest Asia, the Caribbean, and the Middle East have necessitated heightened vigilance, preventive measures, and treatment of cases.10–19

In the planning for overseas military operations, the geography-based presence or absence of the malaria threat is usually known and can be anticipated. However, when preventive countermeasures are needed, their effective implementation is multifaceted and depends on the provision of protective equipment and supplies, individuals' understanding of the threat and attention to personal protective measures, treatment of malaria cases, and medical surveillance. The U.S. Armed Forces have long had policies and prescribed countermeasures effective against vector-borne diseases such as malaria, including chemoprophylactic drugs, permethrin-impregnated uniforms and bed nets, and topical insect repellents containing N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide (DEET). When cases and outbreaks of malaria have occurred, they generally have been due to poor adherence to chemoprophylaxis and other personal preventive measures.11–14

MSMR malaria updates from the past 9 years documented that the annual case counts among service members after 2011 were the lowest in more than a decade.7,20–25 In particular, these updates showed that the numbers of cases associated with service in Afghanistan had decreased substantially in the past 9 years, presumably due to the dramatic reduction in the numbers of service members serving there. This update for 2021 uses methods similar to those employed in previous analyses to describe the epidemiologic patterns of malaria incidence among service members in the active and reserve components of the U.S. Armed Forces.

Methods

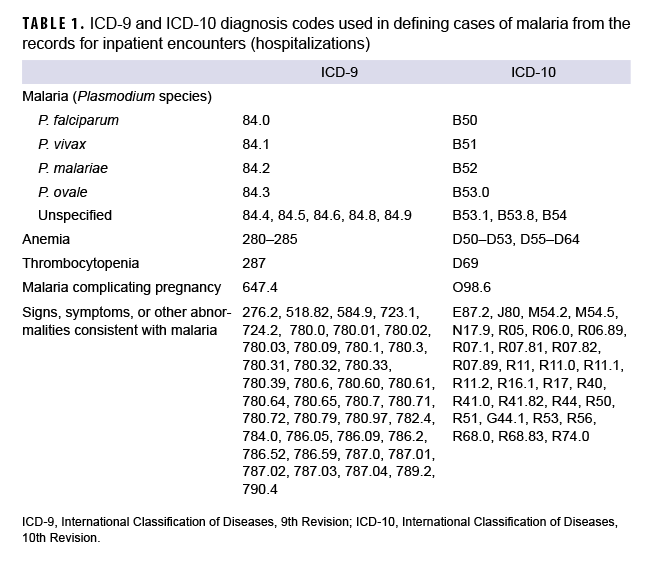

The surveillance period was Jan. 1, 2012 through Dec. 31, 2021. The surveillance population included Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps active and reserve component members of the U.S. Armed Forces. The records of the Defense Medical Surveillance System (DMSS) were searched to identify reportable medical events and hospitalizations (in military and non-military facilities) that included diagnoses of malaria. A case of malaria was defined as an individual with 1) a reportable medical event record of confirmed malaria; 2) a hospitalization record with a primary diagnosis of malaria; 3) a hospitalization record with a nonprimary diagnosis of malaria due to a specific Plasmodium species; 4) a hospitalization record with a nonprimary diagnosis of malaria plus a diagnosis of anemia, thrombocytopenia and related conditions, or malaria complicating pregnancy in any diagnostic position; 5) a hospitalization record with a nonprimary diagnosis of malaria plus diagnoses of signs or symptoms consistent with malaria in each diagnostic position antecedent to malaria;26 or 6) a positive malaria antigen test plus an outpatient record with a diagnosis of malaria in any diagnostic position within 30 days of the specimen collection date. The relevant International Classification of Diseases, 9th and 10th Revision (ICD-9 and ICD-10, respectively) codes are shown in Table 1. Laboratory data for malaria were provided by the Navy and Marine Corps Public Health Center.

This analysis allowed 1 episode of malaria per service member per 365-day period. When multiple records documented a single episode, the date of the earliest encounter was considered the date of clinical onset, and the most specific diagnosis recorded within 30 days of the incident diagnosis was used to classify the Plasmodium species.

Presumed locations of malaria acquisition were estimated using a hierarchical algorithm: 1) cases diagnosed in a malarious country were considered acquired in that country, 2) reportable medical events that listed exposures to malaria-endemic locations were considered acquired in those locations, 3) reportable medical events that did not list exposures to malaria-endemic locations but were reported from installations in malaria-endemic locations were considered acquired in those locations, 4) cases diagnosed among service members during or within 30 days of deployment or assignment to a malarious country were considered acquired in that country, and 5) cases diagnosed among service members who had been deployed or assigned to a malarious country within 2 years before diagnosis were considered acquired in those respective countries. All remaining cases were considered to have acquired malaria in unknown locations.

Results

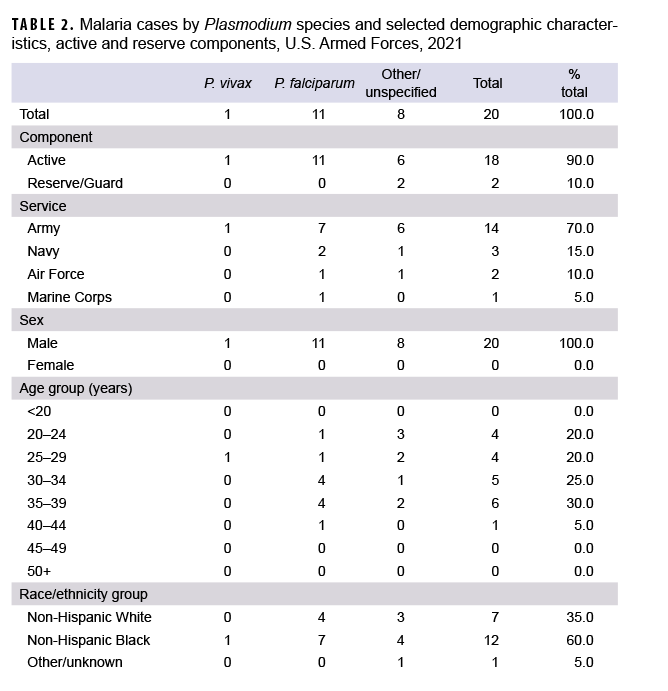

In 2021, a total of 20 service members were diagnosed with or reported to have malaria (Table 2). This total was the lowest number of cases in any given year during the surveillance period and represents a 28.6% decrease from the 28 cases identified in 2020 (Figure 1). Over half of the cases of malaria in 2021 were caused by P. falciparum (55.0%; n=11). Of the 9 cases in 2021 not attributed to P. falciparum, 1 (5.0%) was identified as due to P. vivax and 8 were labeled as associated with other/unspecified types of malaria (40.0%). Malaria cases caused by P. falciparum accounted for the most cases (n=158; 39.2%) during the 10-year surveillance period (Figure 1). Similar to 2020, the majority of U.S. military members diagnosed with malaria in 2021 were male (100.0%), active component members (90.0%), and in the Army (70.0%). In 2021, service members in their 30s (55.0%) accounted for the most cases of malaria (Table 2).

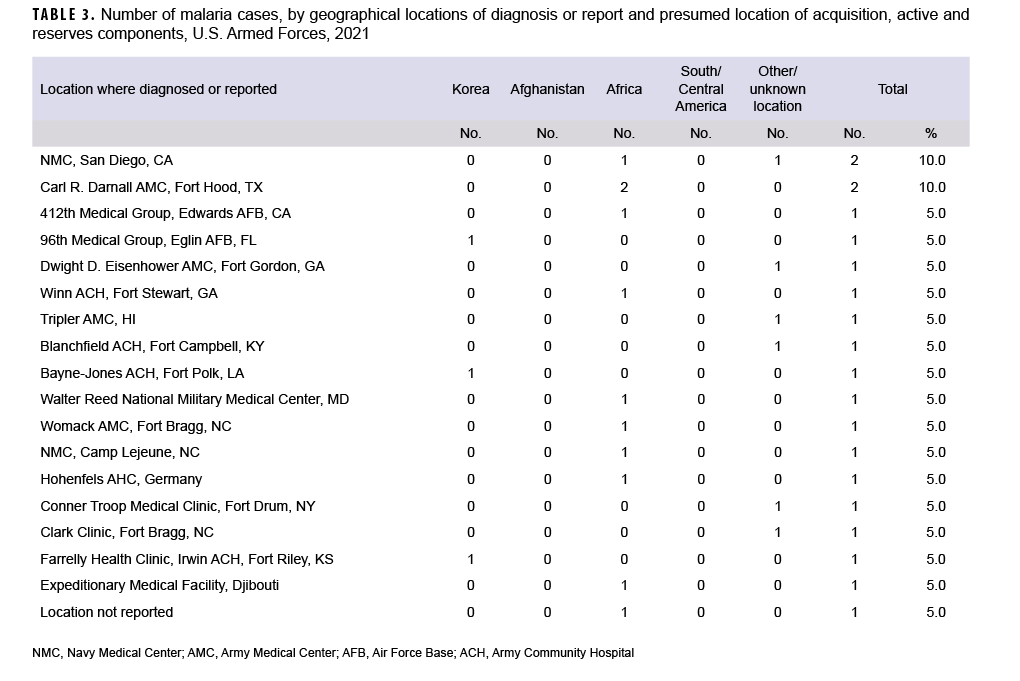

Of the 20 malaria cases in 2021, more than half (55.0%; n=11) were attributed to Africa; 15.0% (n=3) were attributed to Korea, and no infections were considered to have been acquired in Afghanistan or South/Central America (Figure 2). The remaining cases could not be associated with a known, specific location (30.0%; n=6). Of the 11 malaria infections considered acquired in Africa in 2021, 3 were linked to Djibouti; 2 were linked to unknown African locations, and 1 each were linked to Chad, Cameroon, Ghana, Ivory Coast, Sierra Leone, and Nigeria (data not shown).

During 2021, malaria cases were diagnosed or reported from 18 different medical facilities in the U.S., Germany, and Africa (Table 3). Only 10.2% (n=2) of the total cases with a known location of diagnosis were reported from or diagnosed outside the U.S.

In 2021, the percentage of malaria cases that were acquired in Africa (55.0%; n=11) increased from 2020 (20.0%) and was the highest during the surveillance period (Figure 2). The percentage of malaria cases acquired in Korea (15.0%; n=3) in 2021 was similar to the percentage in 2020 (14.3%).

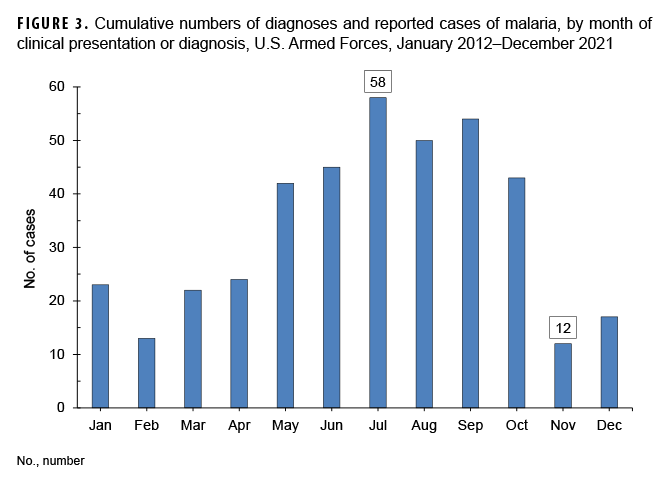

Between 2012 and 2021, the majority of malaria cases were diagnosed or reported during the 6 months from the middle of spring through the middle of autumn in the Northern Hemisphere (Figure 3). In 2021, 65.0% (n=13) of malaria cases among U.S. service members were diagnosed during May–Oct. (data not shown). This proportion is lower than the 72.5% (292/403) of cases diagnosed during the same 6-month intervals over the entire 10-year surveillance period. During 2012–2021, the proportions of malaria cases diagnosed or reported during May–Oct. varied by region of acquisition: Korea (90.2%; 55/61); Afghanistan (79.8%; 83/104); Africa (65.5%; 95/145); and South/Central America (50.0%; 2/4) (data not shown).

Editorial Comment

MSMR annual reports on malaria incidence among all U.S. services began in 2007. The current report documents that the number of malaria cases in 2021 decreased from 2020 and was the lowest of any of the previous years in the 2012–2021 surveillance period. Most of the marked decline in the past 9 years is attributable to the decrease in numbers of malaria cases associated with service in Afghanistan. No cases were considered to have been acquired in Afghanistan in 2021. The dominant factor in that trend has undoubtedly been the progressive withdrawal of U.S. forces from that country.

This report also documents the fluctuating incidence of acquisition of malaria in Africa and Korea among U.S. military members during the past decade. The 2021 percentage of cases caused by P. falciparum (55.5%) was the highest of any year of the surveillance period. This shift is most likely a result of the decrease in cases in Korea and Afghanistan where the predominant species of malaria has been P. vivax.

Malaria caused by the more dangerous P. falciparum species is of primary concern in Africa. The planning and execution of military operations on the African continent must incorporate actions to counter the threat of infection by that potentially deadly parasite wherever it is endemic. The 2014–2015 employment of U.S. service members to aid in the response to the Ebola virus outbreak in West Africa is an example of an operation where the risk of P. falciparum malaria was significant.19,27 The finding that P. falciparum malaria was diagnosed in more than half of the cases in 2021 further underscores the need for continued emphasis on prevention of this disease, given its potential severity and risk of death. Moreover, a recent article noted the possibility of false negative results for P. falciparum on the rapid diagnostic tests favored by units in resource-limited or austere locations.28 Although additional research is needed, commanders and unit leaders may need to be extra vigilant with forces that are far forward.

The observations about the seasonality of diagnoses of malaria are compatible with the presumption that the risk of acquiring and developing symptoms of malaria in a temperate climatic zone of the Northern Hemisphere would be greatest during May–Oct. Given the typical incubation periods of malaria infection (approximately 9–14 days for P. falciparum, 12–18 days for P. vivax and P. ovale, and 18–40 days for P. malariae)26 and the seasonal disappearance of biting mosquitoes during the winter, most malaria acquired in Korea and Afghanistan would be expected to cause symptoms during the warmer months of the year. However, it should be noted that studies of P. vivax malaria in Korea have found that the time between primary infection and clinical illness among different P. vivax strains ranges between 8 days and 8–13 months and that as many as 40–50% of infected individuals may not manifest the symptoms of their primary illness until 6–11 months after infection.29,30 Klein and colleagues reported a cluster of 11 U.S. soldiers with P. vivax malaria who were likely infected at a training area located near the southern border of the demilitarized zone in 2015.31 Nine of the malaria cases developed their first symptoms of infection 9 or more months after exposure and after their departure from Korea.31 Transmission of malaria in tropical regions such as sub-Saharan Africa is less subject to the limitations of the seasons as in temperate climates but depends more on other factors affecting mosquito breeding such as the timing of the rainy season and altitude (below 2,000 meters).32

There are significant limitations to this report that should be considered when interpreting the findings. For example, the ascertainment of malaria cases is likely incomplete; some cases treated in deployed or non-U.S. military medical facilities may not have been reported or otherwise ascertained at the time of this analysis. Furthermore, it should be noted that medical data from sites that used the new electronic health record for the Military Health System, MHS GENESIS, between July 2017 and Oct. 2019 are not available in the DMSS. These sites include Naval Hospital Oak Harbor, Naval Hospital Bremerton, Air Force Medical Services Fairchild, and Madigan Army Medical Center. Therefore, medical encounter data for individuals seeking care at any of these facilities from July 2017 and through 2019 were not included in the current analysis.

Diagnoses of malaria that were documented only in outpatient settings without records of a positive malaria antigen test and that were not reported as notifiable events were not included as cases. Also, the locations of infection acquisitions were estimated from reported relevant information. Some cases had reported exposures in multiple malarious areas, and others had no relevant exposure information. Personal travel to or military activities in malaria-endemic countries were not accounted for unless specified in notifiable event reports.

As in prior years, in 2021 most malaria cases among U.S. military members were treated at medical facilities remote from malaria endemic areas. Providers of acute medical care to service members (in both garrison and deployed settings) should be knowledgeable of and vigilant for the early clinical manifestations of malaria among service members who are or were recently in malaria-endemic areas. Care providers should also be capable of diagnosing malaria (or have access to a clinical laboratory that is proficient in malaria diagnosis) and initiating treatment (particularly when P. falciparum malaria is clinically suspected).

Continued emphasis on adherence to standard malaria prevention protocols is warranted for all military members at risk of malaria. Personal protective measures against malaria include the proper wear of permethrin-treated uniforms and the use of permethrin-treated bed nets; the topical use of military-issued, DEET-containing insect repellent; and compliance with prescribed chemoprophylactic drugs before, during, and after times of exposure in malarious areas. Current Department of Defense guidance about medications for prophylaxis of malaria summarizes the roles of chloroquine, atovaquone-proguanil, doxycycline, mefloquine, primaquine, and tafenoquine.33,34

Acknowledgements: The authors thank the Navy Marine Corps Public Health Center, Portsmouth, VA, for providing laboratory data for this analysis.

References

- World Health Organization. World Malaria Report 2021. WHO, Geneva 2021. Accessed 8 Feb. 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240040496

- Mace KE, Arguin PM, Lucci NW, Tan KR. Malaria Surveillance—United States, 2016. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2019;68(5):1–35.

- Price RN, Commons RJ, Battle KE, Thriemer K, Mendis K. Plasmodium vivax in the era of the shrinking P. falciparum map. Trends Parasitol. 2020;36(6):560–570.

- Battle KE, Lucas TC, Nguyen M, et al. Mapping the global endemicity and clinical burden of Plasmodium vivax, 2000–17: a spatial and temporal modelling study. Lancet. 2019;394(10195):332–343.

- U.S. Army Center for Health Promotion and Preventive Medicine. Malaria, U.S. Army, 1998. MSMR. 1999;5(1):2–3.

- U.S. Army Center for Health Promotion and Preventive Medicine. Malaria experience among U.S. active duty soldiers, 1997-1999. MSMR. 1999;5(8)2–3.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Update: Malaria, U.S. Armed Forces, 2019. MSMR. 2020;27(2):2–7.

- Gupta RK, Gambel JM, Schiefer BA. Personal protection measures against arthropods. In: Kelley PW, ed. Military Preventive Medicine: Mobilization and Deployment, Volume 1. Falls Church, VA: Office of the Surgeon General, Department of the Army; 2003:503–521.

- Ognibene AJ, Barrett O. Malaria: introduction and background. In: Ognibene AJ, Barrett O, eds. Internal Medicine in Vietnam Vol II: General Medicine and Infectious Diseases. Washington, DC: Office of the Surgeon General, Center of Military History; 1982: 271–278.

- Shanks GD, Karwacki JJ. Malaria as a military factor in Southeast Asia. Mil Med.1991; 156(12):684–668.

- Kotwal RS, Wenzel RB, Sterling RA, et al. An outbreak of malaria in U.S. Army Rangers returning from Afghanistan. JAMA. 2005;293(2):212–216.

- Whitman TJ, Coyne PE, Magill AJ, et al. An outbreak of Plasmodium falciparum malaria in U.S. Marines deployed to Liberia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;83(2):258–265.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Malaria acquired in Haiti–2010. MMWR. 2010;59(8):217–218.

- Shaha DP, Pacha LA, Garges EC, Scoville SL, Mancuso JD. Confirmed malaria cases among active component U.S. Army personnel, Jan. –Sept. 2012. MSMR 2013;20(1):6–9.

- Lee JS, Lee WJ, Cho SH, Ree H. Outbreak of vivax malaria in areas adjacent to the demilitarized zone, South Korea, 1998. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002;66(1):13–17.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center (Provisional). Korea-acquired malaria, U.S. Armed Forces, Jan.1998–Oct. 2007. MSMR. 2007;14(8):2–5.

- Ciminera P, Brundage J. Malaria in U.S. military forces: a description of deployment exposures from 2003 through 2005. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;76(2):275–279.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center. Surveillance snapshot: Malaria among deployers to Haiti, U.S. Armed Forces, 13 Jan.–30 June 2010. MSMR. 2010;17(8):11.

- Woods M. Biggest threat to U.S. troops in Liberia is malaria, not Ebola. Published 4 Dec. 2014. Accessed 8 Feb. 2022. https://www.army.mil/article/139340/biggest_threat_to_us_troops_in_liberia_is_malaria_not_ebola

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center. Update: Malaria, U.S. Armed Forces, 2012. MSMR 2013;20(1):2–5.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center. Update: Malaria, U.S. Armed Forces, 2013. MSMR 2014;21(1):4–7.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center. Update: Malaria, U.S. Armed Forces, 2014. MSMR 2015;22(1):2–6.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Update: Malaria, U.S. Armed Forces, 2015. MSMR 2016;23(1):2–6.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Update: Malaria, U.S. Armed Forces, 2016. MSMR 2017;24(1):2–6.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Update: Malaria, U.S. Armed Forces, 2017. MSMR 2018;25(2):2–7.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Surveillance Case Definition: Malaria. February 2019. Accessed Feb. 8, 2022. https://health.mil/Reference-Center/Publications/2014/12/01/Malaria

- Mace KE, Arguin PM, Tan KR. Malaria Surveillance—United States, 2015. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2018;67(7):1–28.

- Forshey BM, Morton L, Martin N, et al. Plasmodium falciparum rapid test failures threaten diagnosis and treatment of U.S. military personnel Mil Med. 2020;185(1–2):e1–e4

- White, NJ. Determinants of relapse periodicity in Plasmodium vivax malaria. Malar J. 2011 (10):297

- Distelhorst JT, Marcum RE, Klein TA, Kim HC, Lee WJ. Report of two cases of vivax malaria in U.S. soldiers and a review of malaria in the Republic of Korea. MSMR. 2014;21(1):8–14.

- Klein TA, Seyoum B, Forshey BM, et al. Cluster of vivax malaria in U.S. soldiers training near the demilitarized zone, Republic of Korea during 2015. MSMR. 2018;25(11):4–9.

- Fairhurst RM, Wellems TE. Plasmodium species (malaria). In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2010.

- Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs. Guidance on Medications for Prophylaxis of Malaria. HA-Policy 13-002. 15 April 2013.

- Defense Health Agency. Procedural Instruction 6490.03. Deployment Health Procedures. 17 Dec. 2019.