Background

The post-9/11 conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan resulted in the most U.S. military casualties since Vietnam.1 Asymmetric warfare dominated the battlefield, commonly in the form of improvised explosive devices and other blast weaponry, which placed infantry and combat support personnel at risk of injury.2 As casualty numbers increased during these conflicts, so too did the survivability rate relative to previous wars, most notably due to advances in personal protective equipment and field medical care.3 This led to a shift in resources towards long-term rehabilitation of wounded service members to ameliorate physical and mental health sequelae.2,4

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is frequently reported among military personnel, particularly those with combat-related injury.5,6 Koren et al.5 hypothesized multiple etiologies for the relationship between combat-related injury and PTSD, including increased levels of perceived threat to life and peritraumatic dissociation (i.e., feeling emotionally numb or separated from a traumatic event) among injured relative to non-injured personnel. An increased incidence of PTSD is associated with physical problems and chronic health conditions after combat-related injury.7,8 Moreover, assessment of PTSD following combat-related injury is essential for planning appropriate treatment protocols and improving long-term well-being.4,9

This report describes the prevalence of screening positive for PTSD and the association with injury severity and time since injury among U.S. military personnel injured during combat operations.

Methods

Data were collected from the Wounded Warrior Recovery Project (WWRP), a longitudinal examination of patient-reported outcomes among service members injured on deployment in post-9/11 conflicts.10 Participants in the WWRP are identified from the Expeditionary Medical Encounter Database (EMED), a deployment health repository maintained by the Naval Health Research Center that includes clinical records of service members injured during overseas contingency operations since 2001. Records are collected throughout the continuum of care (i.e., from point of injury through rehabilitation).11 Individuals who sustained an injury during combat operations after 1 September 2001 are eligible for the WWRP and approached via postal mail and email to provide informed consent to complete biannual assessments for 15 years. Recruitment for the WWRP began in November 2012 and is ongoing.

The present study utilized cross-sectional data for 3,847 WWRP participants collected between September 2018 and April 2020. WWRP measures and procedures were updated in late 2018 to remain consistent with current standards of measurement. Specifically, the PTSD screening instrument was updated to the PTSD Checklist for the DSM-5 (PCL-5).12 The PCL-5 shows good psychometric properties and has been used with military samples.13,14 Scores on the PCL-5 were summed to create a total symptom severity score. A standard cutoff of 33 indicated a positive screen for PTSD. Injury dates, Injury Severity Scores (ISS), and demographics for this study were obtained from the EMED. The ISS is a composite measure of overall injury severity that accounts for multiple injuries to different body regions.15 Prevalence of screening positive for PTSD was calculated and stratified by ISS (mild [ISS 1–3], moderate [ISS 4–8], or serious/severe [ISS 9+]) and time between injury and WWRP assessment in quartiles (0.4–7.3, 7.4–10.7, 10.8–13.0, or 13.1–17.8 years). Chi-square tests assessed differences by PTSD screening status. An alpha level of 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed in SAS/STAT software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

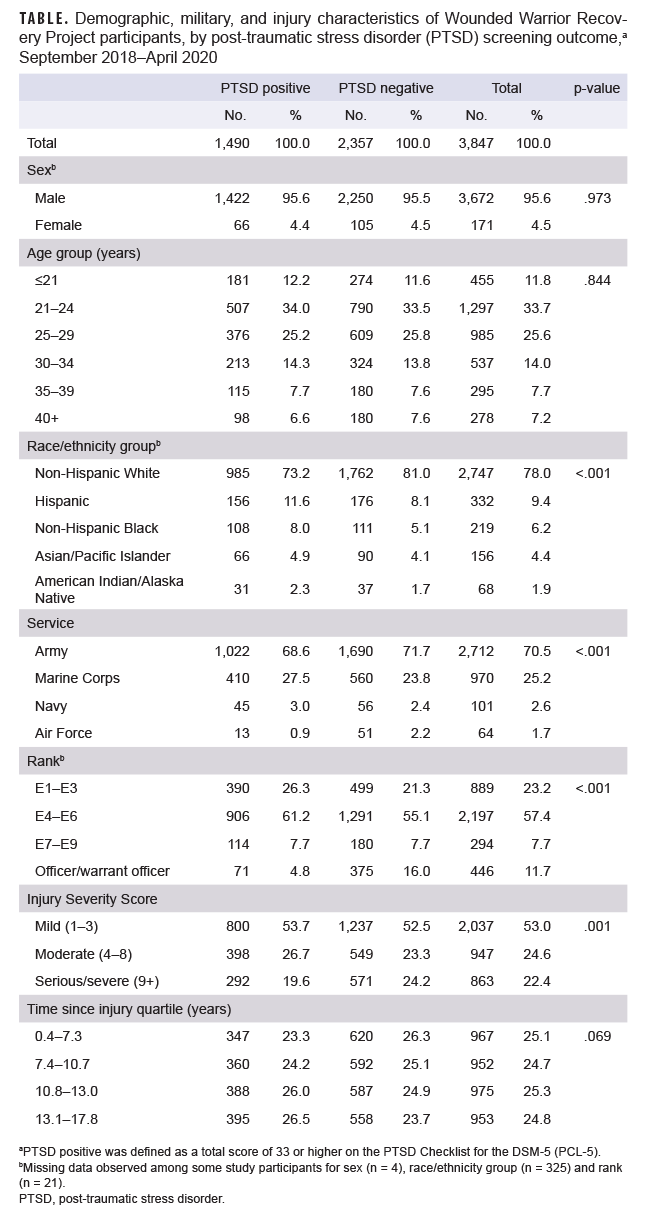

The study population consisted mostly of young (<30 years old), non-Hispanic White, and male service members in the Army with mild ISSs (Table). Missing data were observed for sex (n = 4), race/ethnicity group (n = 325), and rank (n = 21). Approximately half completed a WWRP assessment more than 10.8 years after injury, and 38.7% screened positive for PTSD. Service members who screened positive for PTSD were more likely to be non-White (p <.001), non-Army (p <.001), and lower- to midlevel-enlisted (E1–E6; p <.001) with mild or moderate ISSs (p =.001).

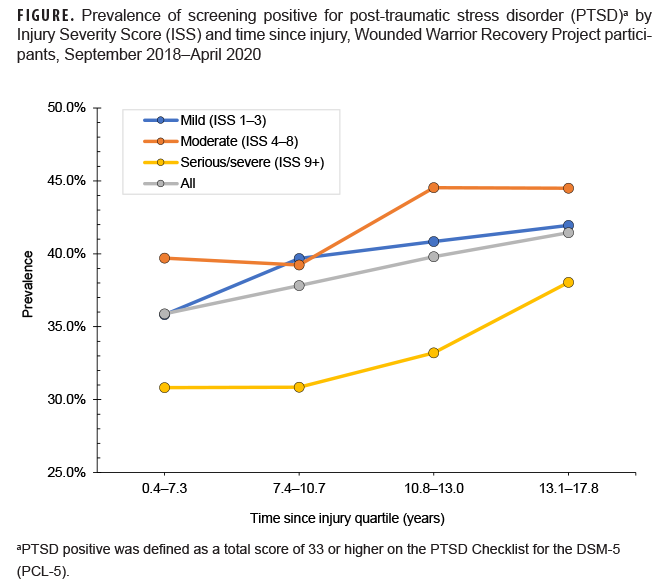

Overall, the proportions of service members who screened positive for PTSD increased by time since injury quartile (Figure); 35.9% of participants who completed an assessment 0.4–7.3 years after injury screened positive for PTSD, compared with 41.4% who completed the assessment 13.1–17.8 years after injury. Participants with serious/severe injuries had the lowest prevalence of screening positive for PTSD in all time since injury quartiles (30.8–38.0%), while those with moderate injuries had the highest prevalence in the final 2 quartiles (44.5%).

Editorial Comment

Approximately 39% of WWRP participants screened positive for PTSD, which is higher than the 28% identified in a previous study using the same instrument among military personnel with high combat exposure.14 Another study among Marines and Soldiers returning from deployment identified 12–13% PTSD positive using a 4-item PTSD screening instrument.16 In the present study, all service members had at least 1 potentially traumatic event (i.e., combat-related injury), which could explain the higher prevalence of participants who screened positive for PTSD relative to other studies.

The finding of increasing prevalence by time since injury suggests that PTSD may develop or persist several years after combat-related injury, and underscores the need for continual assessment. The higher prevalence of screening positive for PTSD in participants with mild or moderate combat-related injuries suggests that PTSD symptoms in these individuals may not have been as promptly or readily identified and treated as in those with serious/severe injuries. Further, service members with serious/severe injuries likely received more extensive care for physical ailments and may have been regularly assessed for mental health symptoms leading to earlier identification, treatment, and resolution. Other aspects of serious/severe combat-related injuries, such as medications received during treatment in-theater, could also explain lower PTSD prevalence in this group.17

The results of this study highlight the importance of screening for PTSD after combat-related injury even after long periods of time. Both the Post-Deployment Health Assessment and Periodic Health Assessment should continue to be used to identify and refer individuals at risk for PTSD. Given that service members may be averse to reporting mental health symptoms due to non-anonymity of these assessments,18 programs aimed at reducing the stigma associated with mental health care in the military should be prioritized.19 In addition, medical providers who treat combat-related injuries should routinely screen service members for mental health concerns, as individuals presenting for physical health complaints may be simultaneously experiencing psychological symptoms.20

There are some limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results of this study. This analysis examined time since injury in mutually exclusive groups, rather than repeated measures within individuals, and thus trajectory of PTSD over time could not be elucidated. Similarly, the WWRP does not collect information related to history of PTSD prior to injury. Further, the specific role of injury on the development of PTSD cannot be clarified without a detailed accounting of other factors (e.g., physical health, comorbidities, and life stressors) following combat-related injury.

In conclusion, service members and veterans with combat-related injuries are at risk of screening positive for PTSD even more than a decade after injury. This warrants future research to explore the role of injury severity and factors associated with resiliency, persistence, and recovery. Resources should be prioritized for early intervention and mitigation in this population during active service and post-military discharge.

Author Affiliations: Naval Health Research Center, San Diego, CA (Dr. MacGregor, Ms. Perez, Dr. McCabe, Ms. Dougherty, Dr. Jurick, and Mr. Galarneau); Axiom Resource Management Inc., San Diego, CA (Dr. MacGregor); Leidos, Inc., San Diego, CA (Ms. Perez, Dr. McCabe, Ms. Dougherty, Dr. Jurick)

Disclaimer: The authors are military service members or employees of the U.S. Government. This work was prepared as part of their official duties. Title 17, U.S.C. §105 provides that copyright protection under this title is not available for any work of the U.S. Government. Title 17, U.S.C. §101 defines a U.S. Government work as work prepared by a military service member or employee of the U.S. Government as part of that person's official duties. This report was supported by the U.S. Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery under work unit no. 60808. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, nor the U.S. Government. The study protocol was approved by the Naval Health Research Center Institutional Review Board in compliance with all applicable Federal regulations governing the protection of human subjects. Research data were derived from an approved Naval Health Research Center Institutional Review Board protocol, number NHRC.2009.0014.

References

- DeBruyne NF, Leland A; Congressional Research Service. American war and military operations casualties: lists and statistics. Accessed 1 June 2021. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/natsec/RL32492.pdf

- Greer N, Sayer N, Kramer M, Koeller E, Velasquez T. Prevalence and epidemiology of combat blast injuries from the military cohort 2001–2014. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs; 2016.

- Cannon JW, Holena DN, Geng Z, et al. Comprehensive analysis of combat casualty outcomes in US service members from the beginning of World War II to the end of Operation Enduring Freedom. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2020;89(Suppl 2):S8–S15.

- Sayer NA, Cifu DX, McNamee S, et al. Rehabilitation needs of combat-injured service members admitted to the VA Polytrauma Rehabilitation Centers: the role of PM&R in the care of wounded warriors. PM R. 2009;1(1):23–28.

- Koren D, Norman D, Cohen A, Berman J, Klein EM. Increased PTSD risk with combat-related injury: a matched comparison study of injured and uninjured soldiers experiencing the same combat events. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(2):276–282.

- Walker LE, Watrous J, Poltavskiy E, et al. Longitudinal mental health outcomes of combat-injured service members. Brain Behav. 2021;11(5):e02088.

- Grieger TA, Cozza SJ, Ursano RJ, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and depression in battle-injured soldiers. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(10):1777–1783.

- Watrous JR, McCabe CT, Jones G, et al. Low back pain, mental health symptoms, and quality of life among injured service members. Health Psychol. 2020;39(7):549–557.

- Woodruff SI, Galarneau MR, McCabe CT, Sack DI, Clouser MC. Health-related quality of life among US military personnel injured in combat: findings from the Wounded Warrior Recovery Project. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(5):1393–1402.

- Watrous JR, Dougherty AL, McCabe CT, Sack DI, Galarneau MR. The Wounded Warrior Recovery Project: a longitudinal examination of patient-reported outcomes among deployment-injured military personnel. Mil Med. 2019;184(3–4):84–89.

- Galarneau MR, Hancock WC, Konoske P, et al. The Navy-Marine Corps Combat Trauma Registry. Mil Med. 2006;171(8):691–697.

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Keane TM, Palmieri PA, Marx BP, Schnurr PP. The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) – Standard [Measurement instrument]. National Center for PTSD Web site. Accessed 1 June 2021. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/documents/PCL5_Standard_form.PDF

- Blevins CA, Weathers FW, Davis MT, Witte TK, Domino JL. The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): development and initial psychometric evaluation. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28(6):489–498.

- Hoge CW, Riviere LA, Wilk JE, Herrell RK, Weathers FW. The prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in US combat soldiers: a head-to-head comparison of DSM-5 versus DSM-IV-TR symptom criteria with the PTSD checklist. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1(4):269–277.

- Baker SP, O'Neill B, Haddon W Jr, Long WB. The injury severity score: a method for describing patients with multiple injuries and evaluating emergency care. J Trauma. 1974;14:187–96.

- Mustillo SA, Kysar-Moon A, Douglas SR, et al. Overview of depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and alcohol misuse among active duty service members returning from Iraq and Afghanistan, self-report and diagnosis. Mil Med. 2015;180(4):419–27.

- Holbrook TL, Galarneau MR, Dye JL, Quinn K, Dougherty AL. Morphine use after combat injury in Iraq and post-traumatic stress disorder. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(2):110–117.

- Warner CH, Appenzeller GN, Grieger T, et al. Importance of anonymity to encourage honest reporting in mental health screening after combat deployment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(10):1065–1071.

- Ben-Zeev D, Corrigan PW, Britt TW, Langford L. Stigma of mental illness and service use in the military. J Ment Health. 2012;21(3):264–273.

- MacGregor AJ, Zouris JM, Watrous JR, et al. Multimorbidity and quality of life after blast-related injury among US military personnel: a cluster analysis of retrospective data. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):578.