By Erin Beech, M.A. and Alexandra Kelly, Ph.D.

Feb. 11, 2019

PHCoE graphic

PHCoE graphic

In our last blog, we discussed how important it is for mental health providers to keep up with the latest psychotherapy research, and covered six types of bias that can occur in randomized clinical trials (RCTs).

Having covered the vulnerabilities of certain study features, today we'll introduce a tool for use in systematically evaluating each of these potential sources of bias and walk you through an example. The aim of this post is to increase providers' confidence and skill in critically evaluating research studies related to the mental health conditions they treat.

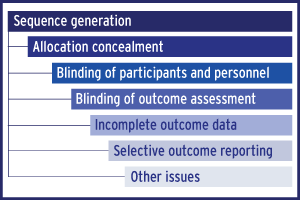

The Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool provides a structure for walking through the design, conduct, analysis, and reporting of findings in RCTs to assess the impact of bias. The tool covers seven domains, and classifies the risk of bias in each as low, moderate, or high.

These seven domains and corresponding types of bias are included in the table below, as well as key questions to ask oneself when evaluating RCT study designs and findings.

| Domain |

Bias Type |

Key Questions |

|

Sequence generation

|

Selection

|

Were participants randomly assigned to groups?

|

|

Allocation concealment

|

Selection

|

Was group assignment concealed from investigators prior to randomization?

|

|

Blinding of participants and personnel

|

Performance

|

Were participants and personnel blind to treatment assignment? Is knowledge of treatment assignment likely to impact outcomes?

|

|

Blinding of outcome assessment

|

Detection

|

Were outcome assessors blind to treatment assignment? Is knowledge of treatment assignment likely to impact outcomes?

|

|

Incomplete outcome data

|

Attrition

|

Were analyses conducted on all randomized participants, and was missing data properly accounted for?

|

|

Selective outcome reporting

|

Reporting

|

Are all pre-specified key outcomes reported on?

|

|

Other issues

|

Other

|

Are there any other potential threats to validity?

|

An Example

PHCoE recently released a new Psych Health Evidence Brief examining the effectiveness of panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy (PFPP) in treating panic disorder in service members. PFPP focuses on identifying a precipitating stressful life event preceding onset of panic disorder symptoms and the meaning (conscious and unconscious) that event has for the patient. Proponents of this treatment assert that the resolution of intrapsychic conflicts should result in better long-term outcomes than treatments focusing on relief of the overt symptoms of panic disorder.

A literature search identified a single randomized control trial evaluating PFPP as a treatment for panic disorder. In this trial, 201 patients diagnosed with panic disorder were randomized to receive PFPP, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), or applied relaxation training (ART).

Using the Cochrane tool framework, the table below shows the risk of bias ratings for the study publication. Readers who have access to the full text are encouraged to read the study and follow along.

| Domain |

Bias Type |

Key Questions |

|

Sequence generation

|

Unclear

|

States only that patients were stratified by site and diagnosis of agoraphobia and depression, and randomized

|

|

Allocation concealment

|

Unclear

|

Not mentioned

|

|

Blinding of participants and personnel

|

High

|

Not feasible in psychotherapy trials

|

|

Blinding of

outcome assessors

|

Low

|

States that outcome assessors were blind to treatment

|

|

Incomplete outcome data

|

Low

|

All but one participant were included in the intention to treat analysis (excluded as ineligible after randomization)

|

|

Selective outcome reporting

|

Low

|

Primary outcome identified in protocol was reported on in the publication

|

|

Other issues

|

High

|

There were significant site-by-treatment interactions that complicate interpretation of the results

|

Evaluation using the risk of bias tool tells us that there are some strong points of this trial, such as blinding of outcome assessment, intention to treat analysis, and reporting of pre-specified primary outcomes. It also highlights bias that is inherent to most psychotherapy trials; participants, as well as personnel delivering the interventions, cannot be blinded to treatment assignment. Meanwhile, the publication does not provide enough information to determine whether there is potential selection bias.

This particular study was conducted at two different sites, and there were significant differences in treatment response between the study sites. The authors report that, at one study site, patients improved at similar rates across the three treatments with no significant between-group differences on the primary outcome measure, whereas at the other site, CBT and ART groups demonstrated significantly better outcomes at treatment termination compared to the PFPP group. These differences could not be explained by characteristics of the sites, such as higher rates of psychotropic medication use by patients at one site than at the other. Because the researchers were not able to identify the reason for the differing results across sites, this represents a potential threat to the validity of the trial.

Ultimately, the risk of bias assessment indicates that these results might overestimate or underestimate the true intervention effect. Therefore, our evidence brief concludes that the current state of evidence on PFPP suggests it should not be recommended as a front-line treatment for panic disorder at this time. Additional comparative effectiveness trials are needed before this treatment can be confidently recommended for consideration by MHS providers.

Curious about the state of the research on other treatments? View all our available Psych Health Evidence Briefs.

Ms. Beech is a senior research associate at the Psychological Health Center of Excellence. She has expertise in evidence synthesis, and is responsible for drafting the Psych Health Evidence Briefs.

Dr. Kelly is a contracted psychological health subject matter expert at the Psychological Health Center of Excellence. She has a master's degree in counseling and psychological services and a doctorate in counseling psychology. She specializes in trauma, vocational psychology, and multicultural counseling.